The analysis of a two-state system (i.e. the rather famous example of an ammonia molecule ‘flipping’ its spin direction from ‘up’ to ‘down’, or vice versa) in my previous post is a good opportunity to think about Occam’s Razor once more. What are we doing? What does the math tell us?

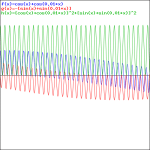

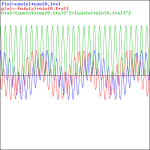

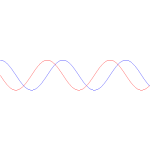

In the example we chose, we didn’t need to worry about space. It was all about time: an evolving state over time. We also knew the answers we wanted to get: if there is some probability for the system to ‘flip’ from one state to another, we know it will, at some point in time. We also want probabilities to add up to one, so we knew the graph below had to be the result we would find: if our molecule can be in two states only, and it starts of in one, then the probability that it will remain in that state will gradually decline, while the probability that it flips into the other state will gradually increase, which is what is depicted below.

However, the graph above is only a Platonic idea: we don’t bother to actually verify what state the molecule is in. If we did, we’d have to ‘re-set’ our t = 0 point, and start all over again. The wavefunction would collapse, as they say, because we’ve made a measurement. However, having said that, yes, in the physicist’s Platonic world of ideas, the probability functions above make perfect sense. They are beautiful. You should note, for example, that P1 (i.e. the probability to be in state 1) and P2 (i.e. the probability to be in state 2) add up to 1 all of the time, so we don’t need to integrate over a cycle or something: so it’s all perfect!

These probability functions are based on ideas that are even more Platonic: interfering amplitudes. Let me explain.

Quantum physics is based on the idea that these probabilities are determined by some wavefunction, a complex-valued amplitude that varies in time and space. It’s a two-dimensional thing, and then it’s not. It’s two-dimensional because it combines a sine and cosine, i.e. a real and an imaginary part, but the argument of the sine and the cosine is the same, and the sine and cosine are the same function, except for a phase shift equal to π. We write:

a·e−iθ = a·cos(θ) – a·sin(−θ) = a·cosθ – a·sinθ

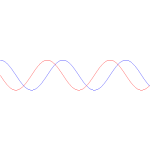

The minus sign is there because it turns out that Nature measures angles, i.e. our phase, clockwise, rather than counterclockwise, so that’s not as per our mathematical convention. But that’s a minor detail, really. [It should give you some food for thought, though.] For the rest, the related graph is as simple as the formula:

Now, the phase of this wavefunction is written as θ = (ω·t − k ∙x). Hence, ω determines how this wavefunction varies in time, and the wavevector k tells us how this wave varies in space. The young Frenchman Comte Louis de Broglie noted the mathematical similarity between the ω·t − k ∙x expression and Einstein’s four-vector product pμxμ = E·t − p∙x, which remains invariant under a Lorentz transformation. He also understood that the Planck-Einstein relation E = ħ·ω actually defines the energy unit and, therefore, that any frequency, any oscillation really, in space or in time, is to be expressed in terms of ħ.

[To be precise, the fundamental quantum of energy is h = ħ·2π, because that’s the energy of one cycle. To illustrate the point, think of the Planck-Einstein relation. It gives us the energy of a photon with frequency f: Eγ = h·f. If we re-write this equation as Eγ/f = h, and we do a dimensional analysis, we get: h = Eγ/f ⇔ 6.626×10−34 joule·second = [x joule]/[f cycles per second] ⇔ h = 6.626×10−34 joule per cycle. It’s only because we are expressing ω and k as angular frequencies (i.e. in radians per second or per meter, rather than in cycles per second or per meter) that we have to think of ħ = h/2π rather than h.]

Louis de Broglie connected the dots between some other equations too. He was fully familiar with the equations determining the phase and group velocity of composite waves, or a wavetrain that actually might represent a wavicle traveling through spacetime. In short, he boldly equated ω with ω = E/ħ and k with k = p/ħ, and all came out alright. It made perfect sense!

I’ve written enough about this. What I want to write about here is how this also makes for the situation on hand: a simple two-state system that depends on time only. So its phase is θ = ω·t = E0/ħ. What’s E0? It is the total energy of the system, including the equivalent energy of the particle’s rest mass and any potential energy that may be there because of the presence of one or the other force field. What about kinetic energy? Well… We said it: in this case, there is no translational or linear momentum, so p = 0. So our Platonic wavefunction reduces to:

a·e−iθ = ae−(i/ħ)·(E0·t)

Great! […] But… Well… No! The problem with this wavefunction is that it yields a constant probability. To be precise, when we take the absolute square of this wavefunction – which is what we do when calculating a probability from a wavefunction − we get P = a2, always. The ‘normalization’ condition (so that’s the condition that probabilities have to add up to one) implies that P1 = P2 = a2 = 1/2. Makes sense, you’ll say, but the problem is that this doesn’t reflect reality: these probabilities do not evolve over time and, hence, our ammonia molecule never ‘flips’ its spin direction from ‘up’ to ‘down’, or vice versa. In short, our wavefunction does not explain reality.

The problem is not unlike the problem we’d had with a similar function relating the momentum and the position of a particle. You’ll remember it: we wrote it as a·e−iθ = ae(i/ħ)·(p·x). [Note that we can write a·e−iθ = a·e−(i/ħ)·(E0·t − p·x) = a·e−(i/ħ)·(E0·t)·e(i/ħ)·(p·x), so we can always split our wavefunction in a ‘time’ and a ‘space’ part.] But then we found that this wavefunction also yielded a constant and equal probability all over space, which implies our particle is everywhere (and, therefore, nowhere, really).

In quantum physics, this problem is solved by introducing uncertainty. Introducing some uncertainty about the energy, or about the momentum, is mathematically equivalent to saying that we’re actually looking at a composite wave, i.e. the sum of a finite or infinite set of component waves. So we have the same ω = E/ħ and k = p/ħ relations, but we apply them to n energy levels, or to some continuous range of energy levels ΔE. It amounts to saying that our wave function doesn’t have a specific frequency: it now has n frequencies, or a range of frequencies Δω = ΔE/ħ.

We know what that does: it ensures our wavefunction is being ‘contained’ in some ‘envelope’. It becomes a wavetrain, or a kind of beat note, as illustrated below:

[The animation also shows the difference between the group and phase velocity: the green dot shows the group velocity, while the red dot travels at the phase velocity.]

This begs the following question: what’s the uncertainty really? Is it an uncertainty in the energy, or is it an uncertainty in the wavefunction? I mean: we have a function relating the energy to a frequency. Introducing some uncertainty about the energy is mathematically equivalent to introducing uncertainty about the frequency. Of course, the answer is: the uncertainty is in both, so it’s in the frequency and in the energy and both are related through the wavefunction. So… Well… Yes. In some way, we’re chasing our own tail. 🙂

However, the trick does the job, and perfectly so. Let me summarize what we did in the previous post: we had the ammonia molecule, i.e. an NH3 molecule, with the nitrogen ‘flipping’ across the hydrogens from time to time, as illustrated below:

This ‘flip’ requires energy, which is why we associate two energy levels with the molecule, rather than just one. We wrote these two energy levels as E0 + A and E0 − A. That assumption solved all of our problems. [Note that we don’t specify what the energy barrier really consists of: moving the center of mass obviously requires some energy, but it is likely that a ‘flip’ also involves overcoming some electrostatic forces, as shown by the reversal of the electric dipole moment in the illustration above.] To be specific, it gave us the following wavefunctions for the amplitude to be in the ‘up’ or ‘1’ state versus the ‘down’ or ‘2’ state respectivelly:

- C1 = (1/2)·e−(i/ħ)·(E0 − A)·t + (1/2)·e−(i/ħ)·(E0 + A)·t

- C2 = (1/2)·e−(i/ħ)·(E0 − A)·t – (1/2)·e−(i/ħ)·(E0 + A)·t

Both are composite waves. To be precise, they are the sum of two component waves with a temporal frequency equal to ω1 = (E0 − A)/ħ and ω1 = (E0 + A)/ħ respectively. [As for the minus sign in front of the second term in the wave equation for C2, −1 = e±iπ, so + (1/2)·e−(i/ħ)·(E0 + A)·t and – (1/2)·e−(i/ħ)·(E0 + A)·t are the same wavefunction: they only differ because their relative phase is shifted by ±π.] So the so-called base states of the molecule themselves are associated with two different energy levels: it’s not like one state has more energy than the other.

You’ll say: so what?

Well… Nothing. That’s it really. That’s all I wanted to say here. The absolute square of those two wavefunctions gives us those time-dependent probabilities above, i.e. the graph we started this post with. So… Well… Done!

You’ll say: where’s the ‘envelope’? Oh! Yes! Let me tell you. The C1(t) and C2(t) equations can be re-written as:

Now, remembering our rules for adding and subtracting complex conjugates (eiθ + e–iθ = 2cosθ and eiθ − e–iθ = 2sinθ), we can re-write this as:

So there we are! We’ve got wave equations whose temporal variation is basically defined by E0 but, on top of that, we have an envelope here: the cos(A·t/ħ) and sin(A·t/ħ) factor respectively. So their magnitude is no longer time-independent: both the phase as well as the amplitude now vary with time. The associated probabilities are the ones we plotted:

- |C1(t)|2 = cos2[(A/ħ)·t], and

- |C2(t)|2 = sin2[(A/ħ)·t].

So, to summarize it all once more, allowing the nitrogen atom to push its way through the three hydrogens, so as to flip to the other side, thereby breaking the energy barrier, is equivalent to associating two energy levels to the ammonia molecule as a whole, thereby introducing some uncertainty, or indefiniteness as to its energy, and that, in turn, gives us the amplitudes and probabilities that we’ve just calculated. [And you may want to note here that the probabilities “sloshing back and forth”, or “dumping into each other” – as Feynman puts it – is the result of the varying magnitudes of our amplitudes, so that’s the ‘envelope’ effect. It’s only because the magnitudes vary in time that their absolute square, i.e. the associated probability, varies too.

So… Well… That’s it. I think this and all of the previous posts served as a nice introduction to quantum physics. More in particular, I hope this post made you appreciate the mathematical framework is not as horrendous as it often seems to be.

When thinking about it, it’s actually all quite straightforward, and it surely respects Occam’s principle of parsimony in philosophical and scientific thought, also know as Occam’s Razor: “When trying to explain something, it is vain to do with more what can be done with less.” So the math we need is the math we need, really: nothing more, nothing less. As I’ve said a couple of times already, Occam would have loved the math behind QM: the physics call for the math, and the math becomes the physics.

That’s what makes it beautiful. 🙂

Post scriptum:

One might think that the addition of a term in the argument in itself would lead to a beat note and, hence, a varying probability but, no! We may look at e−(i/ħ)·(E0 + A)·t as a product of two amplitudes:

e−(i/ħ)·(E0 + A)·t = e−(i/ħ)·E0·t·e−(i/ħ)·A·t

But, when writing this all out, one just gets a cos(α·t+β·t)–sin(α·t+β·t), whose absolute square |cos(α·t+β·t)–sin(α·t+β·t)|2 = 1. However, writing e−(i/ħ)·(E0 + A)·t as a product of two amplitudes in itself is interesting. We multiply amplitudes when an event consists of two sub-events. For example, the amplitude for some particle to go from s to x via some point a is written as:

〈 x | s 〉via a = 〈 x | a 〉〈 a | s 〉

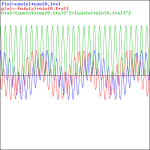

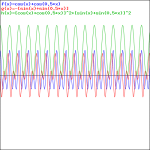

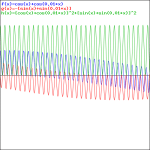

Having said that, the graph of the product is uninteresting: the real and imaginary part of the wavefunction are a simple sine and cosine function, and their absolute square is constant, as shown below.

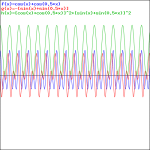

Adding two waves with very different frequencies – A is a fraction of E0 – gives a much more interesting pattern, like the one below, which shows an e−iαt+e−iβt = cos(αt)−i·sin(αt)+cos(βt)−i·sin(βt) = cos(αt)+cos(βt)−i·[sin(αt)+sin(βt)] pattern for α = 1 and β = 0.1.

That doesn’t look a beat note, does it? The graphs below, which use 0.5 and 0.01 for β respectively, are not typical beat notes either.

We get our typical ‘beat note’ only when we’re looking at a wave traveling in space, so then we involve the space variable x again, and the relations that come with in, i.e. a phase velocity vp = ω/k = (E/ħ)/(p/ħ) = E/p = c2/v (read: all component waves travel at the same speed), and a group velocity vg = dω/dk = v (read: the composite wave or wavetrain travels at the classical speed of our particle, so it travels with the particle, so to speak). That’s what’s I’ve shown numerous times already, but I’ll insert one more animation here, just to make sure you see what we’re talking about. [Credit for the animation goes to another site, one on acoustics, actually!]

So what’s left? Nothing much. The only thing you may want to do is to continue thinking about that wavefunction. It’s tempting to think it actually is the particle, somehow. But it isn’t. So what is it then? Well… Nobody knows, really, but I like to think it does travel with the particle. So it’s like a fundamental property of the particle. We need it every time when we try to measure something: its position, its momentum, its spin (i.e. angular momentum) or, in the example of our ammonia molecule, its orientation in space. So the funny thing is that, in quantum mechanics,

- We can measure probabilities only, so there’s always some randomness. That’s how Nature works: we don’t really know what’s happening. We don’t know the internal wheels and gears, so to speak, or the ‘hidden variables’, as one interpretation of quantum mechanics would say. In fact, the most commonly accepted interpretation of quantum mechanics says there are no ‘hidden variables’.

- But then, as Polonius famously put, there is a method in this madness, and the pioneers – I mean Werner Heisenberg, Louis de Broglie, Niels Bohr, Paul Dirac, etcetera – discovered. All probabilities can be found by taking the square of the absolute value of a complex-valued wavefunction (often denoted by Ψ), whose argument, or phase (θ), is given by the de Broglie relations ω = E/ħ and k = p/ħ:

θ = (ω·t − k ∙x) = (E/ħ)·t − (p/ħ)·x

That should be obvious by now, as I’ve written dozens of posts on this by now. 🙂 I still have trouble interpreting this, however—and I am not ashamed, because the Great Ones I just mentioned have trouble with that too. But let’s try to go as far as we can by making a few remarks:

- Adding two terms in math implies the two terms should have the same dimension: we can only add apples to apples, and oranges to oranges. We shouldn’t mix them. Now, the (E/ħ)·t and (p/ħ)·x terms are actually dimensionless: they are pure numbers. So that’s even better. Just check it: energy is expressed in newton·meter (force over distance, remember?) or electronvolts (1 eV = 1.6×10−19 J = 1.6×10−19 N·m); Planck’s constant, as the quantum of action, is expressed in J·s or eV·s; and the unit of (linear) momentum is 1 N·s = 1 kg·m/s = 1 N·s. E/ħ gives a number expressed per second, and p/ħ a number expressed per meter. Therefore, multiplying it by t and x respectively gives us a dimensionless number indeed.

- It’s also an invariant number, which means we’ll always get the same value for it. As mentioned above, that’s because the four-vector product pμxμ = E·t − p∙x is invariant: it doesn’t change when analyzing a phenomenon in one reference frame (e.g. our inertial reference frame) or another (i.e. in a moving frame).

- Now, Planck’s quantum of action h or ħ (they only differ in their dimension: h is measured in cycles per second and ħ is measured in radians per second) is the quantum of energy really. Indeed, if “energy is the currency of the Universe”, and it’s real and/or virtual photons who are exchanging it, then it’s good to know the currency unit is h, i.e. the energy that’s associated with one cycle of a photon.

- It’s not only time and space that are related, as evidenced by the fact that t − x itself is an invariant four-vector, E and p are related too, of course! They are related through the classical velocity of the particle that we’re looking at: E/p = c2/v and, therefore, we can write: E·β = p·c, with β = v/c, i.e. the relative velocity of our particle, as measured as a ratio of the speed of light. Now, I should add that the t − x four-vector is invariant only if we measure time and space in equivalent units. Otherwise, we have to write c·t − x. If we do that, so our unit of distance becomes c meter, rather than one meter, or our unit of time becomes the time that is needed for light to travel one meter, then c = 1, and the E·β = p·c becomes E·β = p, which we also write as β = p/E: the ratio of the energy and the momentum of our particle is its (relative) velocity.

Combining all of the above, we may want to assume that we are measuring energy and momentum in terms of the Planck constant, i.e. the ‘natural’ unit for both. In addition, we may also want to assume that we’re measuring time and distance in equivalent units. Then the equation for the phase of our wavefunctions reduces to:

θ = (ω·t − k ∙x) = E·t − p·x

Now, θ is the argument of a wavefunction, and we can always re-scale such argument by multiplying or dividing it by some constant. It’s just like writing the argument of a wavefunction as v·t–x or (v·t–x)/v = t –x/v with v the velocity of the waveform that we happen to be looking at. [In case you have trouble following this argument, please check the post I did for my kids on waves and wavefunctions.] Now, the energy conservation principle tells us the energy of a free particle won’t change. [Just to remind you, a ‘free particle’ means it is present in a ‘field-free’ space, so our particle is in a region of uniform potential.] You see what I am going to do now: we can, in this case, treat E as a constant, and divide E·t − p·x by E, so we get a re-scaled phase for our wavefunction, which I’ll write as:

φ = (E·t − p·x)/E = t − (p/E)·x = t − β·x

Now that’s the argument of a wavefunction with the argument expressed in distance units. Alternatively, we could also look at p as some constant, as there is no variation in potential energy that will cause a change in momentum, i.e. in kinetic energy. We’d then divide by p and we’d get (E·t − p·x)/p = (E/p)·t − x) = t/β − x, which amounts to the same, as we can always re-scale by multiplying it with β, which would then yield the same t − β·x argument.

The point is, if we measure energy and momentum in terms of the Planck unit (I mean: in terms of the Planck constant, i.e. the quantum of energy), and if we measure time and distance in ‘natural’ units too, i.e. we take the speed of light to be unity, then our Platonic wavefunction becomes as simple as:

Φ(φ) = a·e−iφ = a·e−i(t − β·x)

This is a wonderful formula, but let me first answer your most likely question: why would we use a relative velocity?Well… Just think of it: when everything is said and done, the whole theory of relativity and, hence, the whole of physics, is based on one fundamental and experimentally verified fact: the speed of light is absolute. In whatever reference frame, we will always measure it as 299,792,458 m/s. That’s obvious, you’ll say, but it’s actually the weirdest thing ever if you start thinking about it, and it explains why those Lorentz transformations look so damn complicated. In any case, this fact legitimately establishes c as some kind of absolute measure against which all speeds can be measured. Therefore, it is only natural indeed to express a velocity as some number between 0 and 1. Now that amounts to expressing it as the β = v/c ratio.

Let’s now go back to that Φ(φ) = a·e−iφ = a·e−i(t − β·x) wavefunction. Its temporal frequency ω is equal to one, and its spatial frequency k is equal to β = v/c. It couldn’t be simpler but, of course, we’ve got this remarkably simple result because we re-scaled the argument of our wavefunction using the energy and momentum itself as the scale factor. So, yes, we can re-write the wavefunction of our particle in a particular elegant and simple form using the only information that we have when looking at quantum-mechanical stuff: energy and momentum, because that’s what everything reduces to at that level.

Of course, the analysis above does not include uncertainty. Our information on the energy and the momentum of our particle will be incomplete: we’ll write E = E0 ± σE, and p = p0 ± σp. [I am a bit tired of using the Δ symbol, so I am using the σ symbol here, which denotes a standard deviation of some density function. It underlines the probabilistic, or statistical, nature of our approach.] But, including that, we’ve pretty much explained what quantum physics is about here.

You just need to get used to that complex exponential: e−iφ = cos(−φ) + i·sin(−φ) = cos(φ) − i·sin(φ). Of course, it would have been nice if Nature would have given us a simple sine or cosine function. [Remember the sine and cosine function are actually the same, except for a phase difference of 90 degrees: sin(φ) = cos(π/2−φ) = cos(φ+π/2). So we can go always from one to the other by shifting the origin of our axis.] But… Well… As we’ve shown so many times already, a real-valued wavefunction doesn’t explain the interference we observe, be it interference of electrons or whatever other particles or, for that matter, the interference of electromagnetic waves itself, which, as you know, we also need to look at as a stream of photons , i.e. light quanta, rather than as some kind of infinitely flexible aether that’s undulating, like water or air.

So… Well… Just accept that e−iφ is a very simple periodic function, consisting of two sine waves rather than just one, as illustrated below.

And then you need to think of stuff like this (the animation is taken from Wikipedia), but then with a projection of the sine of those phasors too. It’s all great fun, so I’ll let you play with it now. 🙂

Some content on this page was disabled on June 20, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from Michael A. Gottlieb, Rudolf Pfeiffer, and The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here:

https://wordpress.com/support/copyright-and-the-dmca/

Some content on this page was disabled on June 20, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from Michael A. Gottlieb, Rudolf Pfeiffer, and The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here:

https://wordpress.com/support/copyright-and-the-dmca/

If you would happen to be very young and you want to study something useful, then go for applied science: chemistry, biology or – when you are really smart – engineering or medicine. Something like that. If you want to do physics, go join CERN or something: they probably value engineers or technicians more than theorists there, too! 🙂