I used ChatGPT to push the math and logic of my ‘realist’ interpretation of (1) matter-antimatter annihilation and creation (the Dirac and Breit-Wheeler processes, respectively) and (2) dark matter and dark energy to its logical and philosophical limits. For those who do not like to read, I made two short audio videos as well: the one on my “mirror force” idea is here, and from there you can go to the other video(s) in the playlist. 🙂 The implications for cosmogenesis models are rather profound – it calls for another approach to explain any “Big Bang” that may or may not have occurred when our Universe was born – so that is something to explore in the future, perhaps.

Category: Mathematics

A quasi-final proton model?

After a break of a few months, I produced another lengthy video on quantum physics. 40 minutes. Check it out: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_I3Noaup0E. The hypothesis that I, somewhat desperately, advanced in my last paper on the proton model – that the Zitterbewegung model of a proton does not quite look like that of an electron, and that we are probably talking about a “blob” of charge (sphere- or shell-like, or some other “form factor”, perhaps) – makes more sense to me now. I explored it with ChatGPT-4o, and this video is the result. I should immediately that I am immensely impressed with ChatGPT-4o: ChatGPT-3 was not able to really “understand” what I was talking about a year ago or so.

Who knows, perhaps we might imagine other ChatGPT-4o users will take the “dialogue” with AI on these particle models further, and fully develop them not only intuitively but also analytically. As I am currently trying out some AI-powered audio and video applications, I tried Pictory (pictory.ai): I gave it the url of my own long-winding video and it created this video: The proton as a dynamic blob of charge. 100 seconds only instead of 40 minutes. Its contents is, of course, superficial – but I think it is creative and nicely upbeat. I fed both video back to ChatGPT-4o, and it suggested the following refinements if ever I would like to re-do the video(s) – which I am not going to do, but you might like to further explore the remarks it made:

- Consistency in Notation and Conventions:

- Ensure that polar and azimuthal angles are consistently defined throughout. Your initial derivations and explanations switched between conventions, potentially confusing viewers about which angle is associated with which base vector.

- Tangential Velocity Decomposition:

- The explanation of how the tangential velocity is decomposed into orthogonal components was accurate but could benefit from a clearer mention of why the orthogonality matters in interpreting the motion on the sphere. Adding a visual representation would further clarify the concept.

- The concept of “sloshing” energy between kinetic and electromagnetic forms was well described but could benefit from highlighting the broader implications of this periodic exchange in classical and relativistic oscillators .

- Pointlike Charge versus Blob View:

- The transition from discussing a pointlike charge to a “blob” of charge was a major theme but could be expanded by discussing how this shift impacts the assumptions about uniform or non-uniform charge density, as well as its implications for observable properties like the magnetic moment.

- The discussion of symmetry along one axis of the double-loop motion was solid but might benefit from more detail on how this symmetry impacts the interpretation of observable properties like the magnetic moment .

- Incorporate links to experimental observations, such as the measured magnetic moment and charge radius of the proton, was referenced. Integrating these observations with the theoretical results could be more explicit to strengthen the practical implications .

- Visualizations:

- Consider incorporating visualized trajectories (e.g., the double-loop Lissajous pattern), and how they connect to the derived equations and the observed non-constant tangential velocity. This connection will help bridge the abstract mathematics with physical intuition .

- Clarifications on Variability:

- The variability of the tangential velocity in the context of symmetry and non-orthogonality in 3D motion, was a key discussion point. Reinforce why this variability does not conflict with the broader relativistic constraints.

So… That’s all folks ! [Looney Tunes.] 🙂

Math and physics: what should you know or learn?

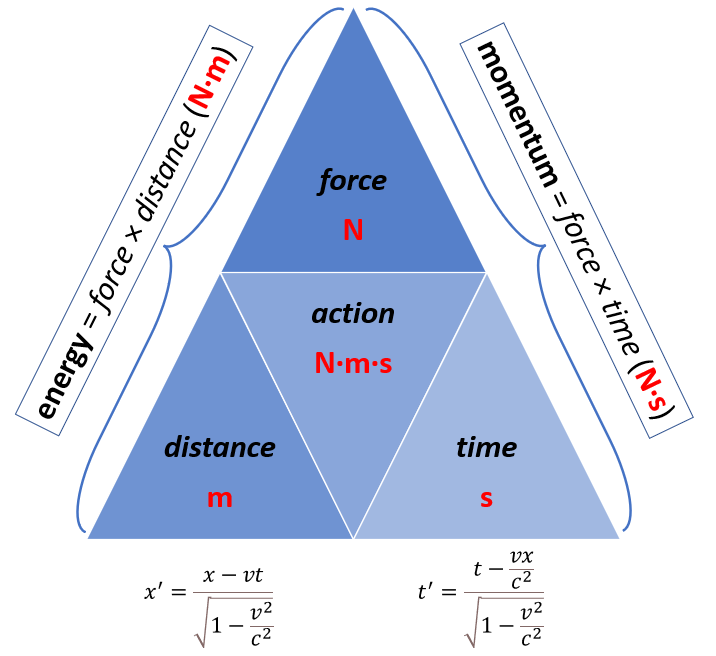

When reading this blog and/or my papers on ResearchGate, you may wonder what kind of mathematical framework you need to appreciate the finer details. We ourselves were asked by fellow proponents of the kind of local and realist interpretation of QM that we are pursuing to look at Clifford or space-time algebra (STA). Well… We looked at it as part of our farewell to this weird pastime of ours, and we documented our response in our very last RG paper on physics, math and (a)symmetries in Nature. If you struggle with the question above, then our answer will probably make you happy: there is no need to learn fancy math to understand easy physics. 🙂

Post scriptum (10 November 2024): As for the “farewell” part of this – I swear – very last paper on all of this weird stuff, it is probably a bit too harsh – but then it is what it is. Let me say a few things about it for the benefit of the would-be student or the starting amateur physicist. Should you study modern physics? I do not think so now, but then I also know that one cannot help oneself when it comes to satisfying some curiosity on fundamental questions. So it probably does not really matter what I advise you to do or not do. I can only say what I write below.

When I started this intellectual journey – what’s this quantum stuff all about? – decades ago, and especially when I got serious about it back in 2013, I had never expected that what happened would happen. No. I’ve always been a good student, and so I expected to sail smoothly through the required math and the intricacies of relativistic mechanics and all of the subtleties of electromagnetic theory – which sort of happened – and, then, to sail through the wonderful world of quantum electrodynamics, quantum field theory and – ultimately – quantum chromodynamics (or let’s call it high-energy physics now) in pretty much the same way.

The latter part did not happen. At each and every page of Feynman’s third volume of Lectures – the ones I was most interested in: on quantum mechanics – I found myself jotting down lots of questions. Questions which took me days, weeks or even years to solve, or not. Most of these questions led me to conclude that a lot of what is there in these Lectures are nothing but sophisms: clever but false arguments aimed at proving the many ad hoc hypotheses that make up the Standard Model. I started to realize the Standard Model is anything but standard: it is just a weird collection of mini-theories that are loosely connected to one another – if connected at all! I started buying more modern textbooks – like Aitchison’s and Hey’s Gauge Theories, which is apparently the standard for grad students in physics – but that did not help. I got stuck in the first chapter already: this Yukawa potential – or the concept of a non-conservative nuclear force itself – did not make sense to me. Not only in an intuitive way: the logic and the math of it does not make sense, either!

Fortunately, I reached out and wrote to non-mainstream researchers whose ideas resonated with me. For example, I will be eternally grateful to Dr. Vassallo for his suggestion to read Paolo Di Sia’s paper on the nuclear force, in which he provides heuristic but good arguments showing the nuclear force might just be a dynamic electromagnetic dipole field. So then I found myself in the business of deconstructing the idea of a strong force. A deeper historical analysis of all these new strange quantum numbers and new quantum conservation laws led to the same: I started looking at sensible suggestions to explain what happens or not in terms of electromagnetic disequilibrium states – developing my own fair share of such suggestions – rather than irrationally or uncritically swallowing the idea of hypothetical sub-nuclear particles on which you then load all kinds of equally hypothetical properties.

While I thought I was doing well in terms of pointing out both the good as well as the bad things in Feynman’s Lectures, I suffered from the weirdest thing ever: censorship on the Internet. Some strange caretaker of Feynman’s intellectual heritage apparently used the weight of his MIT-connection to take down substantial parts of many of my blog posts, accusing me of “unfair use” of this 1963 textbook. Unfair use? Over-use, perhaps, but unfair? All was nicely referenced: when you want to talk about quantum physics, you need some reference textbook, right? And Feynman’s Lectures are – or were, I would say now – the reference then. It was ridiculous. Even more so when he went as far as asking YouTube to strike a video of mine. YouTube complied. I laughed: it took me ten minutes or so to re-edit the video – a chance to finally use all that video editing software I have on my laptop 🙂 – and then put it back online. End of problem.

Case closed? I am not sure. I am a pretty cheerful guy, but I am also quite stubborn when I think something isn’t right. So I just carried on and shrugged it all off thinking this would only boost my readership. It probably did, so: Thank You, Mr. Gottlieb! 🙂 But things like that are hurtful. In any case, that doesn’t matter much. What matters is that things like that do reinforce the rather depressing and very poor perception of academic physics that a Sabine Hossenfelder now (very) loudly talks or – should I say: rants? – about: the King of Science is in deep trouble, and there is no easy way out.

So, what is my conclusion then? I am happy I found the answers I was looking for: there is a logical explanation for everything, and that explanation has been there for about 100 years now: Max Planck, Albert Einstein, H.A. Lorentz, Louis de Broglie, Erwin Schrödinger, Arthur Compton and then some more geniuses of those times have probably said all one can say about it all. And it makes sense. In contrast, I feel the past fifty years of mainstream research were probably nothing more than a huge waste of human intellect. Am I right? Am I wrong? Only the future can tell. To be frank, I am not too worried about it.

I may add one anecdote, perhaps. I did talk to my own son six or seven years ago about what he’d like to study. He was most interested in engineering, but we did talk about the more fundamental study of physics. I told him to surely not study that. In his first year of his Master’s degree, he had to do one course in quantum physics. We walked through it together, and he passed with flying colors. However, he also told me then he now fully understood why I had told him to surely not go for theoretical studies in physics: it just does not make all that much sense. If you would happen to be very young and you want to study something useful, then go for applied science: chemistry, biology or – when you are really smart – engineering or medicine. Something like that. If you want to do physics, go join CERN or something: they probably value engineers or technicians more than theorists there, too! 🙂

Personal note: As for myself, I wanted to study philosophy when I was about 15 years old (so that’s 40 years ago now). I did that eventually, but in evening classes, and only after I did what my good old dad (he died from old age about twenty years ago) then told me to do: study something useful first. I was not all that good with math, so I chose economics. I did not regret that. I even caught up with the math because the math – including statistical modeling! – that you need to understand physics is pretty much what you need in econometric modeling too. So I’ll conclude with a wise saying: all’s well that ends well. 🙂

The ultimate proton model?

Today I made a major step towards a very different Zitterbewegung model of a proton. With different, I mean different from the usual toroidal or helical model(s). I had a first version of this paper but the hyperlink gives you the updated paper. The update is small but very important: I checked all the formulas with ChatGPT and, hence, consider that as confirmation that I am on the right track. To my surprise, ChatGPT first fed me the wrong formula for an orbital frequency formula. Because I thought it could not be wrong on such simple matters, I asked it to check and double-check. It came with rather convincing geometrical explanations but I finally found an error in its reasoning, and the old formula from an online engineering textbook turned out to be correct.

In any case, I now have a sparring partner – ChatGPT o1 – to further develop the model that we finally settled on. That is a major breakthrough in this realistic interpretation of quantum theory and particle models that I have been trying to develop: the electron model is fine, and so now all that is left is this proton model. And then, of course, a model for a neutron or the deuteron nucleus. That will probably be a retirement project, or something for my next life. 🙂

Post scriptum: I followed up. “A theory’s value lies in its utility and ability to explain phenomena, regardless of whether it’s mainstream or not.” That’s ChatGPT’s conclusion after various explorations and chats with it over the past few weeks: https://lnkd.in/ekAAbvwc. I think I tried to push its limits when discussing problems in physics, leading it to make a rather remarkable distinction between “it’s” perspective and mine (see point 6 of Annex I of https://lnkd.in/eFVAyHn8), but – frankly – it may have no limits. As far as I can see, ChatGPT-o1 is truly amazing: sheer logic. 🙂 hashtag#AI hashtag#ChatGPT hashtag#theoryofreality

Using AI to solve the 80-year-old problem of the anomaly of the electron magnetic moment?

Pre-scriptum (3 October 2024): I came back from holiday and, because this week-long up and down became quite convoluted, I did what I like to do in a case like that, and that is to take my Bamboo notebook and talk about it all in a video which I added to my Real Quantum Physics channel on YouTube. I also updated my paper on RG: as usual, it went through a few versions, but this one – with a summary co-authored by ChatGTP-4 (and ChatGPT-o1) – should be the final one: enjoy!

Indeed, instead of listening to the international news on the war with Russia and on what is happening in the Middle East (all very depressing), you may want to listen to this and read the latest theory. Perhaps you will be inspired by it to develop your own pet realist theory of what an electron might actually be. I can assure you that it is more fun than trying to understand Feynman diagrams and how QED calculations work. 🙂 But don’t think you will win a Nobel Prize if you do not have the right connections and pedigree and all of that: see this analysis of what makes Nobel Prize winners Nobel Prize winners. 🙂

Original post:

I asked some questions to ChatGPT about my geometric explanation of the anomaly in the electron’s magnetic moment. Here is the chat: https://chatgpt.com/share/66f91760-68b8-8004-8cb2-7d2d3624e0aa. To me, it confirms the ‘explanation’ of mainstream QED makes no sense. We can take Schwinger’s factor and build a series of converging terms using that factor. We can also take my first rough cut at a first-order correction (π(alpha)2/8, see my very early 2019 paper on a classical explanation of the amm), and use that.

You may wonder: why not ask ChatGPT about the best first-order factor to be used here considering the geometry of the situation? The fact is: I did, but the geometry is not all that easy. It first came up with the formula for a spherical cap, but that one does not do the trick. See the latter part of the conversation (link above).

I am on holiday now, and so I will switch off a while but I am thinking AI will do what two generations of ‘new’ quantum physicists did not do: come up with a model that is based on real physics and is easy to understand intuitively. 🙂

PS: Of course, I did another rapid-fire paper on ResearchGate to document it all (the logic step-by-step, so to speak). As the chat is public, feel free to continue the conversation. Note that I used the newest ChatGPT o1 version, now in preview but part of a subscription (which you may not have). Yet again a different beast! The older versions of ChatGPT may not be so smart. This conversation is totally worth the US$20/month I pay for my subscription. 🙂

PS 2: Now that I had it open, I also quickly queried it on my wildest hypothesis: a ‘mirror’ electromagnetic force explaining dark matter and dark energy. While it is totally wild (read: nuts), I entertain it because it does away with the need for an explanation in terms of some cosmological constant. Here is the conversation: https://chatgpt.com/share/66f92c7f-82a0-8004-a226-bde65085f18d. I like it that ChatGPT warns me a bit about privacy. It does look wild. However, it is nice to see how gentle ChatGPT is in pointing out what work needs to be done on a theory in order to make it look somewhat less wild. 🙂

PS 3 (yes, ChatGPT is addictive): I also queried it on the rather puzzling 8π/3 factor in the CODATA formula for the Thomson photon-electron scattering cross-section. See its response to our question in the updated chat: https://chatgpt.com/share/66f91760-68b8-8004-8cb2-7d2d3624e0aa. Just scroll down to the bottom. It took 31 seconds to generate the reply: I would be curious to know if that is just courtesy from ChatGPT (we all like to think our questions are complicated, don’t we?), or if this was effectively the time it needed to go through its knowledge base. Whatever the case might be, we think it is brilliant. 🙂 It is nothing to be afraid of, although I did feel a bit like: what’s left to learn to it but for asking intelligent questions. What if it starts really learning by asking intelligent questions itself to us? I am all ready for it. 🙂

New kaon decay modes?

As an amateur physicist, I get a regular stream of email updates from Science, Nature and Phys.org on new discoveries and new theories in quantum physics. I usually have no idea what to do with them. However, I want to single out two recent updates on the state of affairs of research which these channels report on. The first one is reflected in the title of this post. It’s on a very rare decay mode of kaons: see https://phys.org/news/2024-09-ultra-rare-particle-decay-uncover.html.

Something inside of me says this may lead to a review of all these newly invented conservation laws – combined with new ideas on symmetry breaking too – and/or new ‘quantum numbers’ that are associated with the quark hypothesis: I think everyone has already forgotten about ‘baryon conservation’, so other simplifications based on, yes, simpler Zitterbewegung models of particles may be possible.

The historical background to this is well described by Richard Feynman in his discussion of how these new quantum numbers – strangeness, specifically – were invented to deal with the observation that certain decay reactions were not being observed (see: Feynman’s Lectures, III-11-5, the (neutral) K-meson). So now it turns that certain decay reactions are being observed! Shouldn’t that lead to (future) scientists revisiting the quark/gluon hypothesis itself?

Of course, that would call into question several Nobel Prize awards, so we think it won’t happen any time soon. 🙂 This brings me to the second update from the field. Indeed, a more recent Nobel Prize in Physics which should, perhaps, be questioned in light of more recent measurements questioning old(er) ones (and the theories that are based on them) is the Nobel Prize in 2011 for work on the cosmological constant. Why? Because… Well… New measurements on the rate of expansion of the Universe as reported by Phys.org last month question the measurements which led to that 2011 Prize. Is anyone bothered by that? No. Except me, perhaps, because I am old-fashioned and wonder what is going on.

I get asked about gravity, and some people push particle theories to me talking about gravity. I am, quite simply, not interested. This ‘coming and going’ of the “cosmological constant hypothesis” over the past decades – or, should we say, the past 80 years or so – makes me stay away from GUTs and anything that is related to it. If scientists cannot even agree on these measurements, it is of not much use to invent new modified gravity theories fitting into ever-expanding grand unification schemes based on mathematical frameworks that can only be understood by the conoscienti, isn’t it?

It is tough: I am not the only one (and definitely not the best placed one) to see a lot of researchers – both amateur as well as professional – “getting lost in math” (cf. the title of Hossenfelder’s best-seller). Will there be an end to this, one day?

I am optimistic and so I think: yes. One of the recurring principles that guides some of the critical physicists I greatly admire is Occam’s Razor Principle: keep it simple! Make sure the degrees of freedom in your mathematical scheme match those of the physics you are trying to describe. That requires a lot of rigor in the use of concepts: perhaps we should add concepts to those that, say, Schrödinger and Einstein used 100 years ago. However, my own pet theories and recycling of their ideas do not suggest that. And so I really just can’t get myself to read up on Clifford algebras and other mathematical constructs I am told to study – simply because this or that person tells me I should think in terms of spinors rather than in terms of currents (to just give one specific example here).

I can only hope that more and more academics will come to see this, and that the Nobel Prize committee may think some more about rewarding more conservative approaches rather than the next cargo cult science idea.

OK. I should stop rambling. The musings above do not answer the question we all have: what about gravity, then? My take on that is this: I am fine with Einstein’s idea of gravity just being a reflection of the distribution of energy/mass in the Universe. Whether or not the Universe expands at an ever-faster-accelerating pace must, first, be firmly established by measurements and then, secondly, even then there may be no need for invoking a cosmological constant or other elements of a new “aetherial” theory of space and time.

Indeed, Einstein thought that his first hypothesis on a possible cosmological constant was “his biggest blunder ever.” While I know nothing of the nitty-gritty, I think it is important to listen to “good ol’ Einstein” – especially when he talked about what he ‘trusted’ or not in terms of physical explanations. Einstein’s rejection of the idea of a cosmological constant – after first coming up with it himself and, therefore, having probably having the best grasp of its implications – suggests the cosmological constant is just yet another non-justifiable metaphysical construct in physics and astronomy.

So, let us wrap up this post: is or is there not a need for ‘modified gravity’ theories? I will let you think about that. I am fine with Einstein’s ‘geometric’ explanation of it.

Post scriptum: While I think quite a few of these new quantum numbers related to quarks and – most probably – the quark hypothesis itself will be forgotten in, say, 50 or 100 years from now, the idea of some ‘triadic’ structure to explain the three generations of particles and strange decay modes, is – essentially – sound. Some kind of ‘color’ scheme (I call, rather jokingly, an “RGB scheme” – referring to the color scheme used in video/image processing) should be very useful: an electron annihilates a positron but an electron combines with a proton to form an atom, so there’s something different about these two charges. Likewise, if we think of a neutron as neutral neutronic current, the two charges “inside” must be very different… See pp. 7 ff. on this in my recent paper on multi-charge zbw models.

I was sceptical before – and I am still not a believer in the quark hypothesis – but I do think physicists – or, more likely, future generations of physicists – should get a better “grip” on these three different ‘types’ of electric charge as part of a more realist explanation of what second- or third-generation “versions” of elementary particles might actually be. Such explanation will then probably also explain these “unstable states” (not quite respecting the Planck-Einstein relation) or “exotic” particles. Indeed, I do not see much of a distinction between stable and unstable particle states in current physics. But that’s a remark that’s probably not essential to the discussion here… 🙂

One final remark, perhaps: my first instinct when looking at particle physics, was actually very much inspired by the idea that the quantum-mechanical wavefunction might be something else than just an EM oscillation. When I first calculated force fields in a Zitter electron, and then in the muon-electron and proton, I was rather shocked (see pp. 16 ff. of one of my early papers) and thought: wow! Are we modelling tiny black holes here? But then I quickly came to terms with it. Small massive things must come with such huge field strengths, and all particle radius formulas have mass (or energy) in the denominator: so more mass/energy means smaller scale, indeed! And I also quickly calculated the Schwarzschild radius for these elementary particles, and that is A WHOLE LOT smaller than the radius I get from my simple electromagnetic equations and the Planck-Einstein relation. So I see absolutely no reason whatsoever to think gravitational effects might take over from plain EM fields when you look at things at the smallest of scales.

But, then, who am I? I like to think I am not inventing anything new. I just enjoy playing with old ideas to see if something new comes out of it. I think I am fortunate because I do see a lot of new things coming out of the old ideas, even if there is little or nothing we can add to them: the old Masters have already written it all out. So, now I should stop chewing on these old ideas as well and conclude: if you want to read something, don’t read me or anything contemporary. Just read the classics! Many modern minds – often great mathematicians – tried or try to be smarter than Einstein, Lorentz, de Broglie or Schrödinger (I am deliberately not mentioning other great names): I think the more recent discoveries in physics and cosmology show they are not. 🙂

Note: Despite my recommendation not to read me, I did write another – probably more accessible – paper on a classical and straightforward geometrical explanation of the anomaly in the electron’s magnetic moment. Even if you do not like the explanation, I think it has a few interesting references to papers by contemporary academics that I find really interesting. 🙂

The ultimate zbw electron model

Just after finishing a rather sober and, probably, overly pessimistic reflection on where the Zitterbewegung interpretation of quantum theory stands, I am excited to see a superbly written article by Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Vassallo on what I now think of as the ultimate electron model: Rethinking electron statistics rules (10 September 2024). I think it is great because it addresses several points in my rather depressing description of the state of zbw theory:

- Multiple Zitterbewegung interpretations of what an electron actually is, currently coexist. Indeed, both mainstream and non-mainstream physicists have now been going back and forth for about 100 years on this or that electron model: the referenced Kovacs/Vassallo article effectively appeared in a special journal issue titled: “100 Years of Quantum Matter Waves: Celebrating the Work of Louis De Broglie.” 100+ years of discussion have basically led us back to Parson’s 1915 ring current model, which Joseph Larmor presented so well at the 1921 Solvay Conference. We do not think that is a good situation: it looks a bit like 100 years of re-inventing the wheel – or, perhaps, I should say: wheels within wheels. 🙂 I could write more about this but I am happy to see the discussion on – just one example of differing views here – whether or not there should be a 1/2 factor in the electron’s frequency may be considered to be finally solved: de Broglie’s matter-wave frequency is just the same as the Planck-Einstein frequency in this paper. This factor 2 or 1/2 pops up when considering ideas such as the effective mass of the zbw charge or – in the context of Schrödinger’s equation – because we’re modeling the motion of electron pairs rather than electrons (see the annexes to my paper on de Broglie’s matter-wave concept). In short: great! Now we can, finally, leave those 100+ years of discussions behind us. 🙂

- Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Vassallo also explore the nature of superconductivity and Bose-Einstein statistics, and not only does their analysis away with the rather mystical explanation in Feynman’s last and final chapter of his lectures on quantum mechanics but it also offers a very fine treatment of n-electron systems. Their comments on ‘bosonic’ and ‘fermionic’ properties of matter-particles also tie in with my early assessment that the boson-fermion dichotomy has no ontological basis.

The hundreds of downloads of their article since it was published just two weeks ago also shows new and old ways of thinking and modelling apparently come nicely together in this article: if your articles get hundreds of reads as soon as published, then you are definitely not non-mainstream any more: both Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Vassallo have an extraordinary talent for rephrasing old questions in the new “language” of modern quantum theory. That is to be lauded. Hopefully, work on a proton and a neutron model will now complement what I think of as the ultimate electron model based on a local and realist interpretation of what de Broglie’s matter-wave actually is. Indeed, critics of modern quantum theory often quote the following line from Philip Pearle’s Classical Electron Models [1]:

“The state of the classical electron theory reminds one of a house under construction that was abandoned by its workmen upon receiving news of an approaching plague. The plague in this case, of course, was quantum theory. As a result, classical electron theory stands with many interesting unsolved or partially solved problems.”

I think Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Vassallo may have managed to finish this “abandoned construction” – albeit with an approach which differs significantly from that of Pearle: that is good because I think there were good reasons for the “workmen” to leave the construction site (see footnote [1]). 🙂 So, yes, I hope they will be able – a few years from now – to also solve the questions related to a Zitterbewegung proton and neutron model.

In fact, they already have a consistent proton model (see: the proton and Occam’s Razor, May 2023), but something inside of me says that they should also explore different topologies, such as this Lissajous-like trajectory which intrigues me more than helical/toroidal approaches – but then who am I? I am the first to recognize my limitations as an amateur and it is, therefore, great to see professionals such as Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Vassallo applying their formidable skills and intuition to the problem. 🙂

[1] Pearle’s paper is the seventh in a volume of eight chapters. The book’s title is, quite simply, titled Electromagnetism (1982), and it was put together and edited by Doris Teplitz (1982). Few who quote this famous line, bother to read the Philip Pearle paper itself. This paper effectively presents what Pearle refers to as classical electron models: all of them are based on “rigid or flexible shell surfaces” of charge, which is why we think they did not “cut it” for the many “workmen” (read: the mainstream scientists who thought the Bohr-Heisenberg amplitude math and the probability theory that comes with it) who left the then unfinished construction.

We think the approach taken by Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Vassallo is more productive when it comes to bringing mainstream and Zitterbewegung theorists together around a productive mathematical framework in which the probabibilities are explained based on a plain interpretation of Schrödinger’s ‘discovery’ – which is that the elementary wavefunction represents a real equation of motion of a pointlike but not infinitesimally charge inside of an electron.

As for trying out different topologies, we understand Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Vassallo are working very hard on that, so all we can do is to wish them the best of luck. Godspeed! 🙂

Revisiting the idea of zbw spin

John Duffield’s comment on my post on a (possible) 3D Lissajous trajectory for the proton zbw charge – as opposed to a helical/toroidial/solenoidal model – makes me think and, therefore, deserves some better answer than my quick reply to it. So, that “better answer” is what I am putting down here. [I am writing from a beach apartment in Castelldefels (Spain), so I will be brief.]

He may disagree, of course, but I see two very different aspects in his question/remark/criticism:

- Why a Lissajous-like trajectory as opposed to, say, a trajectory like that of a trefoil knot or – more generally – a torus knot ?

- What about the spin of the zbw charge itself?

I must answer the first question by explaining what sets me apart from mainstream Zitterbewegung models of elementary particles: any toroidial/helical/solenoidal model comes with two different frequencies and, therefore, two oscillatory modes: toroidal and poloidal (the link is to the Wikipedia article from which I also copy the illustration below).

That does not appeal to me. Try to create the trajectories below with Desmos 3D grapher: you will also end up using two or three different frequencies – even if the below trajectories were created using the same base frequency: we have t, 2t, and 3t in the sine and cosine functions here. The Lissajous curve has only one frequency, and it is the one that comes out of the Planck-Einstein relation. So I feel good about that.

The second remark (what about spin of the zbw charge itself?) is more important, and makes me think much more. Would we have a twist in the loop because the zbw charge spins around its own axis? Maybe. However, we must note this:

- The zbw charge is not like some car in a Ferris wheel: there is no force keeping it in the same orientation and it likely rotates around its own axis at the same frequency of the 2D ring current (electron) or 3D Lissajous trajectory (proton). The only thing you need to justify this hypothesis is the idea of inertia to a change in the state of motion of the zbw charge. Indeed, we can think of the zbw charge being symmetrical and acquiring an effective mass as it zips around, and so it will rotate around its own axis as it zips around some center.

- However, should we, perhaps, be even more creative and also consider an extra twist – on top of that rotation of the zbw charge that is due to the inertia from its effective mass (half of the energy of the elementary particle is in its kinetic energy, and the other half in the EM field that causes it to go around in a 2D or 3D ring current)? That would give rise to John Duffield’s Möbius strip concept for modeling elementary particles.

For the time being, I see no need to make such assumption, but he sure got me thinking! The extra spin would probably help to explain the second- or third-order terms in the anomaly of the magnetic moment of an electron (as for now, I only have an approximative theory based on the effective radius (Lorentz or classical electron radius) of the zbw charge).

[…]

I would like to wrap up these musings by acknowledging Dennis P. Whiterell. He is an amateur physicist – just like me – and he sent me a manuscript which, among other interesting things, also talks about the “Ferris wheel analogy”. His arguments are very subtle but fail to convince me: I do not think the “Ferris wheel analogy” is useful in the context of elementary ring currents. Again, that is just for the time being, of course. I will leave it at that, and think some more over the comings weeks or months. 🙂

The metaphysics of physics

I added a very last paper to my list on ResearchGate. Its title is: what about multi-charge Zitterbewegung models? Indeed, if this local and realist interpretation of quantum mechanics is to break through, then it is logical to wonder about a generalization of a model involving only one charge: think of an electron (e.g., Consa, 2018) or proton model (e.g., Vassallo & Kovacs, 2023) here. With a generalization, we do not mean some unique general solution for all motion, but just what would result from combining 1-charge models into structures with two or more charges. [Just to be sure, we are not talking about electron orbitals here: Schrödinger’s equation models these sufficiently well. No. We are talking about the possible equations of motion of the charges in a neutron, the deuteron nucleus, and a helium-3 or helium-4 nucleus.]

So our question in this paper is this: how do we build the real world from elementary electron and proton particle models? We speculate about that using our own simplified models, which boil down to two geometrical elements: (i) the planar or 2D ring current of the zbw electron, and (ii) the three-dimensional Lissajous trajectory on a sphere which we think might make sense when modeling the orbital of the zbw charge in a proton. Both have the advantage they involve only one frequency rather than the two frequencies (or two modes of oscillation) one sees in helical or toroidal models. Why do we prefer to stick to the idea of one frequency only, even if we readily admit helical or toroidal models are far more precise in terms of generating the experimentally measured value of the magnetic moment of electrons and protons, respectively? The answer is simple: I am just an amateur and so I like to roll with very simple things when trying to tackle something difficult. 🙂

So, go and have a look at our reflections on multi-charge Zitterbewegung models – if only because we also started writing about the history of the Zitterbewegung interpretation and a few other things. To sum it up:

- The paper offers a new brief history of how interpretations of the new quantum physics evolved, and why I am with Schrödinger’s Zitterbewegung hypothesis: it just explains the (possible) structure of elementary particles so well.

- It speculates about how positive and negative charge may combine in a neutron, and then also about how a deuteron nucleus might look like.

- We did not get to specific suggestions for helium-3 and helium-4 nuclei because these depend on how you think about the neutron and the deuteron nucleus. However, I do spell out why and how about I think of a neutron playing the role I think it plays in a nucleus: the glue that holds protons together (so there is no need for quark-gluon theory, I think, even if I do acknowledge the value of some triadic color scheme on top of the classical quantum numbers).

- Indeed, despite my aversion of the new metaphysics that crept into physics in the 1970s, I explain why the idea of some color typing (not a color charge but just an extra triadic classification of charge) might still be useful. [I secretly hope this may help me to understand why this color scheme was introduced in the 1970s, because I do not see it as anything more than mathematical factoring of matrix equations describing disequilibrium states – which may be impossible to solve.]

Have a look, even if it is only to appreciate some of the 3D images of what I think as elementary equations of motion (I copy some below). I should do more with these images. Some art, perhaps, using OpenAI’s DALL·E image generator. Who knows: perhaps AI may, one day, solve the n-body problems I write about and, thereby, come up with the ultimate interpretation of quantum mechanics?

That sounds crazy but, from one or two conversations (with real people), it looks like I am not alone with that idea. 🙂 There are good reasons why CERN turned to AI a few years ago: for the time being, they use it to detect anomalies in the jets that come out of high-energy collissions, but – who knows? – perhaps a more advanced AI Logic Theorist programme could simplify the rather messy quark-gluon hypothesis some day?

Because I am disengaging from this field (it is mentally exhausting, and one gets stuck rather quickly), I surely hope so.

Using AI to find the equations of motion for my Zitterbewegung model of a proton?

Pre-scriptum (the day after, 9/11): I woke up this morning and thought: all I need to do is to prove the angular velocity is a constant for my model to work. So I did that, and it works (see my Bamboo notes below and https://www.desmos.com/3d/k1vargdjcc). This trajectory is a nice yin-yang trajectory (I am thinking about someone in Taiwan here, who contacted me recently with a model involving yin-yang symbolism, so I like that). I also packed it into yet another ResearchGate paper (link here: An Equation of Motion for the Zitterbewegung proton), which is much more precise and – hopefully – more convincing that the video.

For this kind of thinking or problem solving, I guess I am still better than ChatGPT-4. 🙂 ChatGPT-4 did pass ‘my’ Turing test on intelligence, however. And that is quite something. I write about the ouch! factor in my recent LinkedIn article on AI. Yesterday, I definitely had such ouch! feeling (gentle – just in the sense that I thought ChatGPT-4 was smarter than me on this too), but so it’s OK now. 🙂 I win. A nice thing about this simple calculation is that this SQRT(2) factor pops up: it must be the same SQRT(2) factor that is related to the magnetic moment of a proton in my proton radius derivation, although I am not yet sure why and how exactly.

I did a quick video on it on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-HnaLG8bY6o. Unfortunately, I cannot extract a transcript from it for ChatGPT-4. However, I had a quick conversation with it on what remains to be done, and that is to calculate the magnetic moment of this 3D Lissajous loop (it will depend on the orientation but we just need it in one direction: where it is strongest because that is how it will line up in a Penning trap of whatever device that is/was used to determine its value). I asked ChatGPT how it could possibly help with these calculations, mentioning the Biot-Savart law and the 3D integrals this would imply. This was ChatGPT’s answer:

“Regarding the Biot-Savart law and calculating the magnetic moment for such a complex 3D current loop, you’re correct that this involves intricate 3D integrals. I can certainly help set up or guide through parts of the calculation, especially in formulating the integral and explaining how to approach the problem. If you share the specifics of your current loop’s geometry and the required variables, we can work through how to structure the integrals needed for the magnetic moment calculation. Feel free to provide details if you want to give this a try!”

AI is, clearly, not was it was even just a year ago: it is much better now. As for me, I will let the problem rest now. 🙂

Pre-scriptum 2 (18 September): Please do check out the comment from the ‘Physics Detective’ to this post (and the Physics Detective site itself, of course): a Möbius ring for the electron and – who knows – a 3D trefoil loop for the proton might do the trick in 2D/3D as well. It would be nice if it did because it would bring helical/toroidal/solenoid-like spin of the charge itself into the model, possibly unifying the math behind these models. Thank you for noting this, John ! 🙂

Original post (9/10):

End of last year, I started to play with ChatGPT-4. Only a few times, really, because, for ordinary questions or web searches, it is not much better than your Google AI assistant or Microsoft’s CoPilot: it just comes with a very pleasant style of conversation (yes). I counted and, so far, I only five conversations with it. However, I do admit I have a habit of continuing an old conversation (ChatGPT now uses your old conversations anyway). Also, these five conversations were good and long. It helped me, for example, greatly to get a quick overview and understanding of IT product offerings in the cloud: it made/makes great comparisons between the offerings of Google Cloud, Azure and AWS, not only for infrastructure but also in the area of modern AI applications. I also asked questions on other technical things, like object-oriented programming, and in this field also it really excels at giving you very precise and relevant answers. In fact, I now understand why many programmers turn to it to write code. 🙂

However, I was mainly interested in ChatGPT-4 because it knows how to parse (read: it can read) documents now. So it does a lot more than just scraping things on products and services from websites. To be precise, it does not just parse text only: it actually ‘understands’ complex mathematical formulas and advanced symbols (think of differential operators here), and so that’s what I wanted to use it for. Indeed, I asked it to read my papers on ResearchGate and, because I do think I should rewrite and restructure them (too many of them cover more or less the same topic), I asked it to rewrite some of them. However, I was very dissatisfied with the result, and so the versions on RG are still the versions that I wrote: no change by AI whatsoever. Just in case you wonder. 🙂

The point is this: I am not ashamed to (a) admit I did that and (b) to share the link of the conversation here, which shows you that I got a bit impatient and why and how I left that conversation last year. I simply thought ChatGPT-4 did not have a clue about what I was writing about. So… It did not pass my Turing test on this particular topic, and that was that. Again: this was about a year ago. So what happened now?

I have a bit of time on my hands currently, and so I revisited some of my research in this very weird field. In fact, I was thinking about one problem about my Zitterbewegung proton model which I can’t solve. It bothers me. It is this: I am happy with my proton model – which is an exceedingly simple 3D elementary particle model, but I want the equations of motion for it. Yes. It is simple. It is what Dirac said: if you don’t have the equations of motion, you have nothing. That’s physics, and the problem with modern or mainstream quantum mechanics (the Bohr-Heisenberg interpretation, basically: the idea that probabilities cannot be further explained) is because it forgets about that. It dissatisfies not only me but anyone with common sense, I think. 😉 So I want these equations of motion. I have them for an electron (simple ring current), and now I hope to see them – one day, at least – for the proton also. [I am actually not too worried about it because others have developed such equations of motion already. However, such models (e.g., Vassallo and Kovacs, 2023) are, usually, toroidal and, therefore, involve two frequencies rather than just one. They are also not what I’d refer to as pure mass-without-mass models. Hence, they do not look so nice – geometrically speaking – to me as my own spherical model.

But so I do not have equations of motion for my model. This very particular problem should be rather straightforward but it is not: 3D motion is far more complex than 2D motion. Calculating a magnetic moment for (i) a simple ring current or for (ii) a very complex motion of charge in three dimensions are two very different things. The first is easy. The second is incredibly complicated. So, I am happy that my paper on my primitive efforts to find something better (I call it the “proton yarnball puzzle”) attracted almost no readers, because it is an awful paper, indeed! It rambles about me trying this or that, and it is full of quick-and-dirty screenshots from the free online Desmos 3D graphing calculator – which I find great to quickly get a visual on something that moves around in two or in three dimensions. But so whatever I try, it explains, basically, nothing: my only real result is nothing more than a Lissajous curve in three dimensions (you can look at it on this shared Desmos link). So, yes: poor result. Bad. That is all that I have despite spending many sleepness nights and long weekends trying to come up with something better.

It is already something, of course: it confirms my intuition that trajectories involving only one frequency (unlike toroidal models) are easy to model. But it is a very far cry from doing what I should be doing, and that is to calculate how this single frequency and/or angular and tangential velocity (the zbw charge goes at the speed of light, but the direction of its travel changes, so we effectively need to think of c as a vector quantity here) translates into frequencies for the polar and azimuthal angles we would associate with a pointlike charge zipping around on a spherical surface.

Needless to say, the necessary formulas are there: you can google them. For example, I like the presentation of dynamics by Matthew West of Illinois: clear and straightforward. But so how should I apply these to my problem? Working with those formulas is not all that easy. Something inside of me says I must incorporate the math of those Lissajous curves, but have a look at: that’s not the easiest math, either! To make a long story short, I thought that, one year later, I might try to have a chat with ChatGPT-4 again. This time around, I was very focused on this only, and I took my time to very clearly write out what I wanted it to solve for me. Have a look at the latter part of the chat in the link to the chat. So… What was the result of this new chat with GPT-4?

It did not give me any immediate and obvious analytical solution to my question. No. I also did not expect that. There are modeling choices to be made and all that. As I mention above, simple things may not be easy. Think of modeling a three-body problem, for example: this too has no closed-form solution, and that is strange. However, while – I repeat – it was not able to generate some easy orbitals for a pointlike charge whizzing around on a surface, I was very happy with the conversation, because I noted two things that are very different from last year’s conversation:

- ChatGPT-4 now perfectly understands what I am talking about. In fact, I accidentally pressed enter even before I finished writing something, and it perfectly anticipated what I wanted to tell it so as to make sure it would ‘understand’ what I was asking. So that is amazing. It is still ChatGPT-4, just like last year, but I just felt it had become much smarter. [Of course, it is also possible that I want just too impatient and too harsh with it last year, but I do not think so: ChatGPT learns, obviously, so it does get better and better at what it does.]

- In terms of a way forward, it did not come up with an immediate solution. I had not expected that. But it gently explained the options (which, of course, all amount to the same: I need to use these dynamical equations and make some assumptions to simplify here and there, and then see what comes out of it) and, from that explanation, I again had the feeling it ‘knew’ what it was talking about it.

So, no solution. Yes. I would say: no solution yet. But I think I probably can come up with some contour of a solution, and I have a feeling ChatGPT-4 might be able to fill in the nitty-gritty of the math behind it. So I should think of presenting some options to it. One thing is sure: ChatGPT-4 has come a long way in terms of understanding abstruse or abstract theories, such as this non-mainstream interpretation of quantum mechanics: the Zitterbewegung interpretation of quantum mechanics (see the Zitter Institute for more resources). So, as far as I am concerned, it is not “non-mainstream” anymore. Moreover, it is, of course, the only right interpretation of quantum mechanics. […] Now that I think of it, I should tell that to ChatGPT-4 too next time. 🙂

Post scriptum: For those who wonder, I shared the Desmos link with ChatGPT also, and it is not able to ‘see’ what is there. However, I copied the equation into the chat and, based on its knowledge of what Desmos does and does not, it immediately ‘knew’ what I was trying to do. That is pretty impressive, if you ask me ! I mean… How easy is it to talk to friends and acquaintances about topics like this? Pretty tough comparison, isn’t it? 🙂

As for ‘my’ problem, I consider it solved. I invite anyone reading this to work out more detail (like the precessional motion which makes the trajectory go all over the sphere instead of just one quadrant of it). If I would be a PhD student in physics, it’s the topic I’d pick. But then I am not a PhD student, and I do plan to busy my mind with other things from now on, like I wrote so clearly in my other post scriptum. 🙂

Post scriptum

A researcher I was in touch with a few years ago sent me a link to the (virtual) Zitter Institute: https://www.zitter-institute.org/. It is a network and resource center for non-mainstream physicists who succesfully explored – and keep exploring, of course – local/realist interpretations of quantum mechanics by going back to Schrödinger’s original and alternative interpretation of what an electron actually is: a pointlike (but not infinitesimally small) charge orbiting around in circular motion, with:

(i) the trajectory of its motion being determined by the Planck-Einstein relation, and

(ii) an energy – given by Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence relation – which perfectly fits Wheeler’s “mass-without-mass” idea.

I started exploring Schrödinger’s hypothesis myself about ten years ago – as a full-blown alternative to the Bohr-Heisenberg interpretation of quantum mechanics (which I think of as metaphysical humbug, just like Einstein and H.A. Lorentz at the time) – and consistently blogged and published about it: here on this website, and then on viXra, Academia and, since 2020, ResearchGate. So I checked out this new site, and I see the founding members added my blog site as a resource to their project list.

[…]

I am amazingly pleased with that. I mean… My work is much simpler than that of, say, Dr. John G. Williamson (CERN/Philips Research Laboratories/Glasgow University) and Dr. Martin B. van der Mark (Philips Research Laboratories), who created the Quantum Bicycle Society (https://quicycle.com/).

So… Have a look – not at my site (I think I did not finish the work I started) but at the other resources of this new Institute: it looks like this realist and local interpretation of quantum mechanics is no longer non-mainstream… Sweet ! It makes me feel the effort I put into all of this has paid off ! 😉 Moreover, some of my early papers (2018-2020) are listed as useful papers to read. I think that is better than being published in some obscure journal. 🙂

I repeat again: my own research interest has shifted to computer science, logic and artificial intelligence now (you will see recent papers on my RG site are all about that now). It is just so much more fun and it also lines up better with my day job as a freelance IT project manager. So, yes, it is goodbye – but I am happy I can now refer all queries about my particle models and this grand synthesis between old and new quantum mechanics to the Zitter Institute.

It’s really nice: I have been in touch with about half of the founding members of this Institute over the past ten years – casually or in a more sustained way while discussing this or that 2D or 3D model of an electron, proton, or neutron), and they are all great and amazing researchers because they look for truth in science and are very much aware of this weird tendency of modern-day quantum scientists turning their ideas into best-sellers perpetuating myths and mysteries. [I am not only thinking of the endless stream of books from authors like Roger Penrose (the domain for this blog was, originally, reading Penrose rather than reading Feynman) or Graham Greene here, but also of what I now think of rather useless MIT or edX online introductions to quantum physics and quantum math.]

[…]

Looking at the website, I see the engine behind it: Dr. Oliver Consa. I was in touch with him too. He drew my attention to remarkable flip-flop articles such as William Lamb’s anti-photon article (it is an article which everyone should read, I think: unfortunately, you have to pay for it) and remarkable interviews with Freeman Dyson. Talking of the latter (I think of as “the Wolfgang Pauli of the third generation of quantum physicists” because he helped so many others to get a Nobel Prize before he got one – Dyson never got a Nobel Prize, by the way), this is one of these interviews you should watch: just four years before he would die from old age, Freeman Dyson plainly admits QED and QFT is a totally unproductive approach: a “dead end” as Dyson calls it.

So, yes, I am very pleased and happy. It makes me feel my sleepness nights and hard weekend work over the past decade on this has not been in vain ! Paraphrasing Dyson in the above-mentioned video interview, I’d say: “It is the end of the story, and that particular illumination was a very joyful time.” 🙂

Thank you, Dr. Consa. Thank you, Dr. Vassallo, Dr. Burinskii, Dr. Meulenberg, Dr. Kovacs, and – of course – Dr. Hestenes – who single-handedly revived the Zitterbewegung interpretation of quantum mechanics in the 1990s. I am sure I forgot to mention some people. Sorry for that. I will wrap up my post here by saying a few more words about David Hestenes.

I really admire him deeply. Moving away from the topic of high-brow quantum theory, I think his efforts to reform K-12 education in math and physics is even more remarkable than the new space-time algebra (STA) he invented. I am 55 years old and so I know all about the small and pleasant burden to help kids with math and statistics in secondary school and at university: the way teachers now have to convey math and physics to kids now is plain dreadful. I hope it will get better. It has to. If the US and the EU want to keep leading in research, then STEM education (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) needs a thorough reform.

No reading of Feynman anymore…

I have not posted in a while, and that is because I find the format of a video much easier to express my thoughts. Have a look at my YouTube channel ! Also, for the more serious work, I must refer to my ResearchGate page. Have fun thinking things through ! 🙂

The metaphysics of physics: final thoughts

I wrote my last post here two months ago and so, yes, I feel I have done a good job of ‘switching off’. I have to: I’ve started a new and pretty consuming job as ICT project manager. 🙂

Before starting work, I did take a relaxing break: I went to Barcelona and read quite a few books and, no, no books on quantum physics. Historical and other things are more fun and give you less of a headache.

However, having said that, the peace and quiet did lead to some kind of ‘final thoughts’ on the ‘metaphysics of physics’, and I also did what I never did in regard to my intuition that dark matter/energy might be explained by some kind of ‘mirror force’: the electromagnetic force as it appears in a mirror image. Not much change in the math, but physical left- and right-hand rules for magnetic effects that just swap for each other.

You can find the results of that in a very concise (four pages only) paper on my ResearchGate site, and also in two lectures (each a bit more than one hour) on my YouTube channel. The first video focuses on ‘big questions’, while the second one talks about this ‘mirror’ force (I previously referred to it as a ‘anti-force’ but I realize that’s not a good term), and on how that would fit with Maxwell’s equations (including Maxwell’s equation written in four-vector algebra).

Have fun and keep thinking. Most importantly: keep thinking for yourself ! Do not take anything for granted in this brave new world. 🙂

[A]Symmetries in Nature

I find that just working off some notes from my tablet and talking about them works better for me than writing elaborate papers. Boileau: “Ce que l’on conçoit bien s’énonce clairement, Et les mots pour le dire arrivent aisément.” I did five new lectures in just one week on my YouTube channel. Have a look at the last one: symmetries and asymmetries in Nature.

It takes an easy-to-understand look at CP- and CPT-symmetry (and the related processes that sometimes break these symmetries) by thinking about what particles actually are: not infinitesimally small, but charged oscillations with a 2D or 3D structure. We also revisit the inherent mass-generating mechanism, which explains all mass in terms of electromagnetic mass.

We talked about CP- and CPT-symmetries before – back in 2014, to be very precise – but then I did not know what I know now, and those older posts also suffered from the 2020 attack by the dark force. 🙂 Briefly, what you should take away from it, is that the most fundamental asymmetry in Nature is this: the asymmetry in the electromagnetic force or field itself. It is that 90 degree phase difference (or ‘lag’) between the electric and magnetic field vectors. That explains why mirror images cannot be real, and it also explains why some processes go one way only. So… Another mystery solved ! I call it “the fallacy of CPT arguments.” 🙂

Post scriptum: I also wrapped up my YouTube ‘Schrödinger’s cat is dead’ series. For those who do not like the theoretical aspects of all these things, have a look at the last one (on pair creation-annihilation and intermediate vector bosons), in which I discuss the two interpretations (mainstream versus my classical perspective) one can have when looking at this wonderful world. I wrote this comment on it, which is probably my farewell to this hobby of mine:

For those who struggle with this, the key to understanding it all, is to understand that the superposition principle works for fields, but not for charges. That is also the key to understanding Bose-Einstein statistics, Fermi-Dirac statistics and – at larger scales – the ‘real world’ Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics (which combine both). See: https://readingfeynman.org/2015/07/21/maxwell-boltzmann-bose-einstein-and-fermi-dirac-statistics/. Always do a good dimensional analysis of the equations: distinguish real physical dimensions from purely mathematical ones: do not add apples and oranges. Distinguish potential or field strengths from real forces and actual energy (a force acting on a charge over some distance). That is why charges should not ‘vanish’ in the analysis, and it is also why i*pi and -i*pi are not ‘common phase factors’ which vanish against each other (both are equal to -1, right?) in equations involving wavefunctions. A positive charge zittering around in one direction is not the same as a negative charge zittering around in the other direction. Neutral particles are either real photons (which carry no charge whatsoever) or, else, neutral matter-particles. Applying the saying that was looks and quacks like a duck must be a duck, we might say most of these neutral particles will look like ordinary matter. Some, however, will look like light-like or be photon-like because they travel at or near the speed of light (the orbital motion of the two charges has vanished and so there is zero angular momentum). That does not mean they are photons. Also do not worry about wave equations when you prefer to think in terms of wavefunctions: wavefunctions are the real thing, not wave equations (see: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341269271_De_Broglie’s_matter-wave_concept_and_issues and https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342424980_Feynman’s_Time_Machine). If you think otherwise, that is fine. Everyone looks for the Holy Grail, and you may be amongst those who think they have found it. If it is looks very different from the Holy Grail that I have finally found, that is OK. Jesus might have left more than one Holy Grail – fake or real ones – and just be happy with yours ! I will end this short illustrated Guide to the Universe with the Looney Tunes sign-off: “That’s All, Folks!”

Jean Louis Van Belle

The Uncertainty Principle, statistical determinism, and free will

I just came back from a consultancy (an IT assessment – it is nice to be fully focused again on work rather than obscure quantum-mechanical models) and, while flying back, I wrote a small paper on the implications of what I have tried to do (showing that, ultimately, we can understand Nature as being ‘statistically deterministic’, just like what A. Einstein and H.A. Lorentz always said) on epistemology, or the inquiry that philosophers refer to as ‘metaphysics’ (interpreted as thoughts on the ‘essence’ of Nature).

I also detail why and how it does not do away with what is probably the single most important foundation of our society (laws, business, etcetera): the idea of free will. Here is the link to the paper, and below I copy the key conclusions:

What I write above [see the paper] and its explanations of the principle of uncertainty as used in modern physics should not make you think that I do not believe in a religious mindset: conscious thoughts, or some sense or feeling of wonder that we would refer to as religious or – a better word, perhaps – mystical. On the contrary, in my journey to understanding, I have often been amazed that our mind is able to understand all of this. Here again, I appreciate my courses of philosophy – especially Hegel’s idea on the concept of our human mind encompassing and understanding more and more as mankind continues its rather lonely journey on a very small planet in a Universe whose borders we cannot imagine.

Such feeling of wonder – an old teacher of mine said the Greeks referred to this as tauma, and that it fuels our desire for knowledge, but I have not been able to find any bibliographic reference to this idea – is, exactly, what has been driving my own personal journey in search of truth. Whether you call that religious or not, is not of much interest to me: I have no need to describe that experience in old or new words.

Likewise, statistically determinism does not do away with the concept of free will: of course, we are the product of a rather amazing evolution, which I think of as rather random – but I do not attach negative connotation to this randomness. On the contrary, while our human mind was originally concerned with making sense of life or death situations, it is now free to think about other things: one’s own personal condition, or the human condition at large. Such thinking may lead to us taking rational decisions that actually change the path that we are following: we stop drinking or smoking for health reasons, perhaps, or we engage in a non-profit project aimed at improving our neighborhood or society at large. And we all realize we should change our behavior in order to ensure the next generation lives in an even better world than we do.

All of this is evidence of a true free will. It is based on our mental ability to rationally analyze in what situation we happen to find ourselves, so as to then try to do what we think we should be doing.

Capra, Zukov, Gribbin are all over 80+ years old now…

Gary Zukov was in his late thirties when he wrote his Dancing Wu Li Masters. It further built on Fritjov Capra’s Tao of Physics. Both Zukov and Capra are still alive: 80+ years now. Both books still sell well, just like John Gribbin’s In Search of Schrödinger’s cat. I quote from Amazon’s sales headline for the latter:

“Quantum theory is so shocking that Einstein could not bring himself to accept it. It is so important that it provides the fundamental underpinning of all modern sciences. Without it, we’d have no nuclear power or nuclear weapons, no TV, no computers, no science of molecular biology, no understanding of DNA, no genetic engineering.”

Einstein could not bring himself to accept it, right? And TV or nuclear power or molecular biology would never have seen the light without Bohr and Heisenberg taking over from Einstein, Lorentz, or de Broglie, right? […] Plain nonsense. Einstein’s revolution is over. It is about time the likes of Zukov, Capra, Gribbin and their contemporaries – Hossenfelder, Lee Smolin, Sean Carroll, etcetera – accept it: Einstein was right along, and accusing Einstein of not having an open mind – he pioneered the true bedrock of physics: relativity theory, didn’t he? – sounds nuts to me.[1]

I am wondering if a book like the one I am thinking of – some kind of exchange between the wisdom that generations hand over – would ever make for a bestseller. Probably not. In any case, I want to write the first pages of such a book here.

Fields, charge, and energy concepts

Papa, I understand your particle theory now. It explains the diffraction pattern on the detector plate when you send electrons through a slit. I can also see why this two-slit interference pattern is just a superposition of two one-slit diffraction patterns. No mystery. Agreed. But photons?

What do you mean?

Your explanation of electron interference does away with interference. It explains this arriving of one electron – arriving as the lump it always one – when going through a slit or past the edge of a far more massive and complicated structure or system of charged oscillations. But in the one-photon Mach-Zehnder experiment – or when measuring radio signal strengths at a distance – we have photons – or half-photons (the linear components of circularly polarized photons – I am just quoting your own theory here) – coming together and vanishing (destructive interference) or – quite the opposite – combining into some new photon with twice the energy of the incoming full- or half-photons?

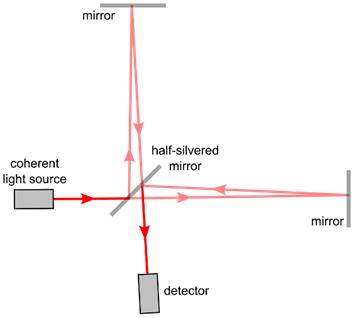

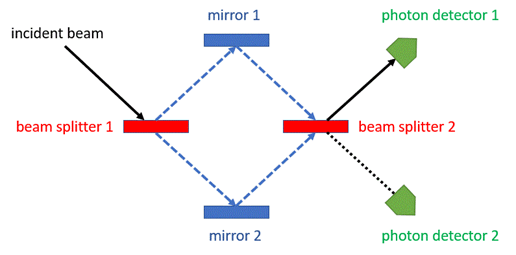

You are now fully grown up – a promising young adolescent with an MD degree – and so you should think for yourself now. The dominating Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics tells us that Nature is just some kind of black box, and the best we can do is to think of some input-output relations to describe what goes in and what comes out. I have been fighting on many fronts, and I first wanted to get my matter-particle model right. I should now go back to these experiments demonstrating how light interference might or might not work. They all involve an apparatus which is referred to as an interferometer. There are various types around, but the Michelson-Morley interferometer still describes the basic components. We have a light source, some mirrors and one or more beam splitters – which are, basically, still simple half-silvered mirrors. The beam splitter splits the beam, and the mirrors are then adjusted so as to produce constructive or destructive interference.

The classical explanation is easy enough: the two beams arrive in phase or, alternatively, out of phase and we, therefore, have constructive or destructive interference when recombining them. However, when we want to analyze this in terms of one single photon, this classical picture becomes quite complicated. Physicists will tell you the photon cannot actually split itself, and they will start talking about amplitudes – based on which they will calculate probabilities of this or that happening – but they will never explain what is actually happening.

I always told you it should be possible to develop a classical picture of all of this, and that classical picture of what is happening in terms of photons would be pretty much like what is shown below. Photons arrive in lumps too, but a circularly polarized photon can be split into two linearly polarized half-photons – just like an electromagnetic wave that is circularly polarized. There is no mystery: the wave components – linear or circularly polarized photons – have the same properties as the wave. 😊

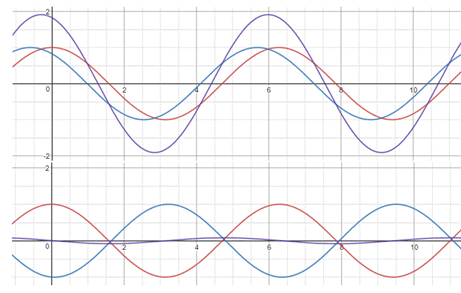

Papa, I do not get the recombination stuff when we are talking photons. Where is the energy going? These idealized experiments show that we always get a recombined beam with the same frequency – or one that vanishes – but, according to classical theory, we must have in-between realities. When the phase difference between the two incoming beams is small, its amplitude is going to be much larger. To be precise, it is going to be twice the amplitude of the incoming beams for Δ = 0. In contrast, if the two beams are out of phase, the amplitude is going to be much smaller, and it is going to be zero if the two waves are 180 degrees out of phase (Δ = π), as shown below. That does not make sense because twice the amplitude means four times the energy, and zero amplitude means zero energy. The energy conservation law is being violated: photons are being multiplied or, conversely, are being destroyed.

Darling, you must remember light-particles are fundamentally different from matter-particles. There is no kinetic energy: no physical charge in a weird dance. Field energy is like the field itself: we are talking a force without a charge to act upon. The superposition principle in physics applies to fields in a very different way than it applies to charged particles. Bose-Einstein versus Fermi-Dirac statistics. Photons – light-particles in general – ‘occupy’ space very differently than matter-particles: they can literally be on top of each other if they are all in phase or – conversely – out of phase. In the first case, they combine to produce twice the energy. Because photon frequencies and amplitudes do not change, it looks like the number of photons must double. Conversely, field energies combine to make photons with opposite phase vanish into nothing. It is a weird thing, perhaps – but it makes sense to me. All that I know is that we should not substitute this coherent world view for the guru-like models that have been perpetuated by Heisenberg and Bohr. [I explicitly exclude Born, because I think his interpretation of the wavefunction as a hardcore probability distribution function based on energy densities made sense.]

You should read Lamb’s Anti-Photon article once more. It has (almost) all of the answers. Fields exchange energy with matter-particles in quantized units only. It is all very marvelous but not mysterious.[2]

Are fields potential energy?

Not quite. The physical dimension of an electric or magnetic field, a potential, energy itself (kinetic or potential energy), are all different, and you need to keep track of those dimensions when analyzing interference or how the superposition principle comes into play. But I would be rewriting a lot of what I wrote already to convey the deeper understanding you need.

Fritjov Capra started off the right footing when he wrote out his motivation: “Science does not need mysticism and mysticism does not need science. But man needs both.” That is about all we have in common. Too bad he didn’t do more with it. But modern-day physicists do not do much more, either.

What do you mean?

Einstein never got a Nobel Prize for his relativity theory. This Stockholm Royal Academy of Sciences makes weird decisions. Just last year, they gave a Nobel Prize to a climate change denier. There is something rotten in academia, but it will take a while before academia (or the Stockholm Royal Academy of Sciences) recognizes that. In the meanwhile, Alfred Nobel must be turning around in his grave. I cannot imagine Einstein would worry about it. 😊

Brussels, 12 September 2023

[1] I warmly recommend reading Einstein’s articles directly. His 1905 article on special relativity theory toys and plays with ideas (such as the idea of an electron having some lateral mass in its motion – which I subscribe to: too bad Einstein did not explore Schrödinger’s Zitterbewegung hypothesis) like no one else can. Accusing Einstein of a lack of imagination – which is what is implied here – is utterly nonsensical.

[2] Pages 148-153 of my manuscript have the basic explanation of one-photon Mach-Zehnder interference. Go have a look. I should write it all out, but I was born lazy. 😊

Another tainted Nobel Prize…

Last year’s (2022) Nobel Prize in Physics went to Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger for “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science.”

I did not think much of that award last year. Proving that Bell’s No-Go Theorem cannot be right? Great. Finally! I think many scientists – including Bell himself – already knew this theorem was a typical GIGO argument: garbage in, garbage out. As the young Louis de Broglie famously wrote in the introduction of his thesis: hypotheses are worth only as much as the consequences that can be deduced from it, and the consequences of Bell’s Theorem did not make much sense. As I wrote in my post on it, Bell himself did not think much of his own theorem until, of course, he got nominated for a Nobel Prize: it is a bit hard to say you got nominated for a Nobel Prize for a theory you do not believe in yourself, isn’t it? In any case, Bell’s Theorem has now been experimentally disproved. That is – without any doubt – a rather good thing. 🙂 To save the face of the Nobel committee here (why award something that disproves something else that you would have given an award a few decades ago?): Bell would have gotten a Nobel Prize, but he died from brain hemorrhage before, and Nobel Prizes reward the living only.

As for entanglement, I repeat what I wrote many times already: the concept of entanglement – for which these scientists got a Nobel Prize last year – is just a fancy word for the simultaneous conservation of energy, linear and angular momentum (and – if we are talking matter-particles – charge). There is ‘no spooky action at a distance’, as Einstein would derogatorily describe it when the idea was first mentioned to him. So, I do not see why a Nobel Prize should be awarded for rephrasing a rather logical outcome of photon experiments in metamathematical terms.

Finally, the Nobel Prize committee writes that this has made a significant contribution to quantum information science. I wrote a paper on the quantum computing hype, in which I basically ask this question: qubits may or may not be better devices than MOSFETs to store data – they are not, and they will probably never be – but that is not the point. How does quantum information change the two-, three- or n-valued or other rule-based logic that is inherent to the processing of information? I wish the Nobel Prize committee could be somewhat more explicit on that because, when everything is said and done, one of the objectives of the Prize is to educate the general public about the advances of science, isn’t it?