This post explores the limits of the physical interpretation of the wavefunction we have been building up in previous posts. It does so by examining if it can be used to provide a hidden-variable theory for explaining quantum-mechanical interference. The hidden variable is the polarization state of the photon.

The outcome is as expected: the theory does not work. Hence, this paper clearly shows the limits of any physical or geometric interpretation of the wavefunction.

This post sounds somewhat academic because it is, in fact, a draft of a paper I might try to turn into an article for a journal. There is a useful addendum to the post below: it offers a more sophisticated analysis of linear and circular polarization states (see: Linear and Circular Polarization States in the Mach-Zehnder Experiment). Have fun with it !

A physical interpretation of the wavefunction

Duns Scotus wrote: pluralitas non est ponenda sine necessitate. Plurality is not to be posited without necessity.[1] And William of Ockham gave us the intuitive lex parsimoniae: the simplest solution tends to be the correct one.[2] But redundancy in the description does not seem to bother physicists. When explaining the basic axioms of quantum physics in his famous Lectures on quantum mechanics, Richard Feynman writes:

“We are not particularly interested in the mathematical problem of finding the minimum set of independent axioms that will give all the laws as consequences. Redundant truth does not bother us. We are satisfied if we have a set that is complete and not apparently inconsistent.”[3]

Also, most introductory courses on quantum mechanics will show that both ψ = exp(iθ) = exp[i(kx-ωt)] and ψ* = exp(-iθ) = exp[-i(kx-ωt)] = exp[i(ωt-kx)] = -ψ are acceptable waveforms for a particle that is propagating in the x-direction. Both have the required mathematical properties (as opposed to, say, some real-valued sinusoid). We would then think some proof should follow of why one would be better than the other or, preferably, one would expect as a discussion on what these two mathematical possibilities might represent¾but, no. That does not happen. The physicists conclude that “the choice is a matter of convention and, happily, most physicists use the same convention.”[4]

Instead of making a choice here, we could, perhaps, use the various mathematical possibilities to incorporate spin in the description, as real-life particles – think of electrons and photons here – have two spin states[5] (up or down), as shown below.

Table 1: Matching mathematical possibilities with physical realities?[6]

| Spin and direction |

Spin up |

Spin down |

| Positive x-direction |

ψ = exp[i(kx-ωt)] |

ψ* = exp[i(ωt-kx)] |

| Negative x-direction |

χ = exp[i(ωt-kx)] |

χ* = exp[i(kx+ωt)] |

That would make sense – for several reasons. First, theoretical spin-zero particles do not exist and we should therefore, perhaps, not use the wavefunction to describe them. More importantly, it is relatively easy to show that the weird 720-degree symmetry of spin-1/2 particles collapses into an ordinary 360-degree symmetry and that we, therefore, would have no need to describe them using spinors and other complicated mathematical objects.[7] Indeed, the 720-degree symmetry of the wavefunction for spin-1/2 particles is based on an assumption that the amplitudes C’up = -Cup and C’down = -Cdown represent the same state—the same physical reality. As Feynman puts it: “Both amplitudes are just multiplied by −1 which gives back the original physical system. It is a case of a common phase change.”[8]

In the physical interpretation given in Table 1, these amplitudes do not represent the same state: the minus sign effectively reverses the spin direction. Putting a minus sign in front of the wavefunction amounts to taking its complex conjugate: -ψ = ψ*. But what about the common phase change? There is no common phase change here: Feynman’s argument derives the C’up = -Cup and C’down = -Cdown identities from the following equations: C’up = eiπCup and C’down = e–iπCdown. The two phase factors are not the same: +π and -π are not the same. In a geometric interpretation of the wavefunction, +π is a counterclockwise rotation over 180 degrees, while -π is a clockwise rotation. We end up at the same point (-1), but it matters how we get there: -1 is a complex number with two different meanings.

We have written about this at length and, hence, we will not repeat ourselves here.[9] However, this realization – that one of the key propositions in quantum mechanics is basically flawed – led us to try to question an axiom in quantum math that is much more fundamental: the loss of determinism in the description of interference.

The reader should feel reassured: the attempt is, ultimately, not successful—but it is an interesting exercise.

The loss of determinism in quantum mechanics

The standard MIT course on quantum physics vaguely introduces Bell’s Theorem – labeled as a proof of what is referred to as the inevitable loss of determinism in quantum mechanics – early on. The argument is as follows. If we have a polarizer whose optical axis is aligned with, say, the x-direction, and we have light coming in that is polarized along some other direction, forming an angle α with the x-direction, then we know – from experiment – that the intensity of the light (or the fraction of the beam’s energy, to be precise) that goes through the polarizer will be equal to cos2α.

But, in quantum mechanics, we need to analyze this in terms of photons: a fraction cos2α of the photons must go through (because photons carry energy and that’s the fraction of the energy that is transmitted) and a fraction 1-cos2α must be absorbed. The mentioned MIT course then writes the following:

“If all the photons are identical, why is it that what happens to one photon does not happen to all of them? The answer in quantum mechanics is that there is indeed a loss of determinism. No one can predict if a photon will go through or will get absorbed. The best anyone can do is to predict probabilities. Two escape routes suggest themselves. Perhaps the polarizer is not really a homogeneous object and depending exactly on where the photon is it either gets absorbed or goes through. Experiments show this is not the case.

A more intriguing possibility was suggested by Einstein and others. A possible way out, they claimed, was the existence of hidden variables. The photons, while apparently identical, would have other hidden properties, not currently understood, that would determine with certainty which photon goes through and which photon gets absorbed. Hidden variable theories would seem to be untestable, but surprisingly they can be tested. Through the work of John Bell and others, physicists have devised clever experiments that rule out most versions of hidden variable theories. No one has figured out how to restore determinism to quantum mechanics. It seems to be an impossible task.”[10]

The student is left bewildered here. Are there only two escape routes? And is this the way how polarization works, really? Are all photons identical? The Uncertainty Principle tells us that their momentum, position, or energy will be somewhat random. Hence, we do not need to assume that the polarizer is nonhomogeneous, but we need to think of what might distinguish the individual photons.

Considering the nature of the problem – a photon goes through or it doesn’t – it would be nice if we could find a binary identifier. The most obvious candidate for a hidden variable would be the polarization direction. If we say that light is polarized along the x-direction, we should, perhaps, distinguish between a plus and a minus direction? Let us explore this idea.

Linear polarization states

The simple experiment above – linearly polarized light going through a polaroid – involves linearly polarized light. We can easily distinguish between left- and right-hand circular polarization, but if we have linearly polarized light, can we distinguish between a plus and a minus direction? Maybe. Maybe not. We can surely think about different relative phases and how that could potentially have an impact on the interaction with the molecules in the polarizer.

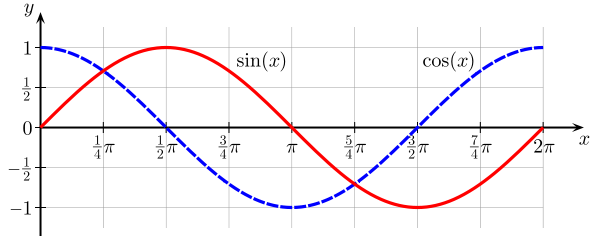

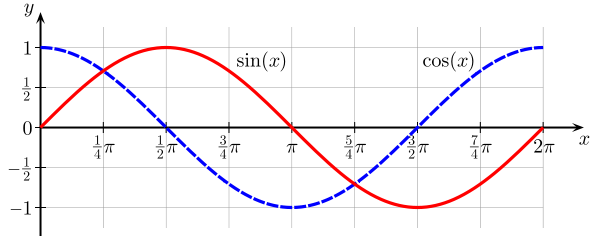

Suppose the light is polarized along the x-direction. We know the component of the electric field vector along the y-axis[11] will then be equal to Ey = 0, and the magnitude of the x-component of E will be given by a sinusoid. However, here we have two distinct possibilities: Ex = cos(ω·t) or, alternatively, Ex = sin(ω·t). These are the same functions but – crucially important – with a phase difference of 90°: sin(ω·t) = cos(ω·t + π/2).

Figure 1: Two varieties of linearly polarized light?[12]

Would this matter? Sure. We can easily come up with some classical explanations of why this would matter. Think, for example, of birefringent material being defined in terms of quarter-wave plates. In fact, the more obvious question is: why would this not make a difference?

Of course, this triggers another question: why would we have two possibilities only? What if we add an additional 90° shift to the phase? We know that cos(ω·t + π) = –cos(ω·t). We cannot reduce this to cos(ω·t) or sin(ω·t). Hence, if we think in terms of 90° phase differences, then –cos(ω·t) = cos(ω·t + π) and –sin(ω·t) = sin(ω·t + π) are different waveforms too. In fact, why should we think in terms of 90° phase shifts only? Why shouldn’t we think of a continuum of linear polarization states?

We have no sensible answer to that question. We can only say: this is quantum mechanics. We think of a photon as a spin-one particle and, for that matter, as a rather particular one, because it misses the zero state: it is either up, or down. We may now also assume two (linear) polarization states for the molecules in our polarizer and suggest a basic theory of interaction that may or may not explain this very basic fact: a photon gets absorbed, or it gets transmitted. The theory is that if the photon and the molecule are in the same (linear) polarization state, then we will have constructive interference and, somehow, a photon gets through.[13] If the linear polarization states are opposite, then we will have destructive interference and, somehow, the photon is absorbed. Hence, our hidden variables theory for the simple situation that we discussed above (a photon does or does not go through a polarizer) can be summarized as follows:

| Linear polarization state |

Incoming photon up (+) |

Incoming photon down (-) |

| Polarizer molecule up (+) |

Constructive interference: photon goes through |

Destructive interference: photon is absorbed |

| Polarizer molecule down (-) |

Destructive interference: photon is absorbed |

Constructive interference: photon goes through |

Nice. No loss of determinism here. But does it work? The quantum-mechanical mathematical framework is not there to explain how a polarizer could possibly work. It is there to explain the interference of a particle with itself. In Feynman’s words, this is the phenomenon “which is impossible, absolutely impossible, to explain in any classical way, and which has in it the heart of quantum mechanics.”[14]

So, let us try our new theory of polarization states as a hidden variable on one of those interference experiments. Let us choose the standard one: the Mach-Zehnder interferometer experiment.

Polarization states as hidden variables in the Mach-Zehnder experiment

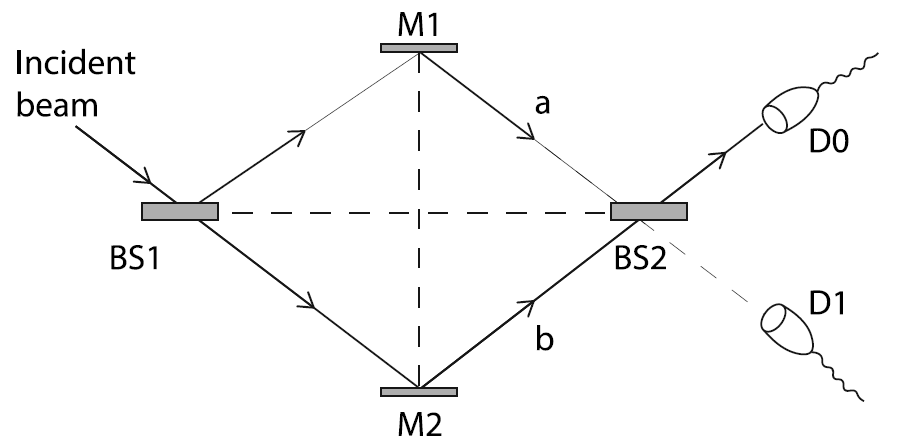

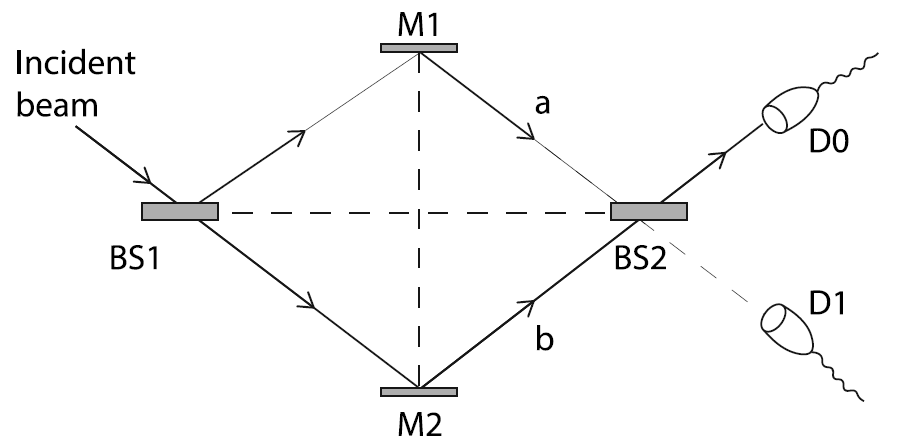

The setup of the Mach-Zehnder interferometer is well known and should, therefore, probably not require any explanation. We have two beam splitters (BS1 and BS2) and two perfect mirrors (M1 and M2). An incident beam coming from the left is split at BS1 and recombines at BS2, which sends two outgoing beams to the photon detectors D0 and D1. More importantly, the interferometer can be set up to produce a precise interference effect which ensures all the light goes into D0, as shown below. Alternatively, the setup may be altered to ensure all the light goes into D1.

Figure 2: The Mach-Zehnder interferometer[15]

The classical explanation is easy enough. It is only when we think of the beam as consisting of individual photons that we get in trouble. Each photon must then, somehow, interfere with itself which, in turn, requires the photon to, somehow, go through both branches of the interferometer at the same time. This is solved by the magical concept of the probability amplitude: we think of two contributions a and b (see the illustration above) which, just like a wave, interfere to produce the desired result¾except that we are told that we should not try to think of these contributions as actual waves.

So that is the quantum-mechanical explanation and it sounds crazy and so we do not want to believe it. Our hidden variable theory should now show the photon does travel along one path only. If the apparatus is set up to get all photons in the D0 detector, then we might, perhaps, have a sequence of events like this:

| Photon polarization |

At BS1 |

At BS2 |

Final result |

| Up (+) |

Photon is reflected |

Photon is reflected |

Photon goes to D0 |

| Down (–) |

Photon is transmitted |

Photon is transmitted |

Photon goes to D0 |

Of course, we may also set up the apparatus to get all photons in the D1 detector, in which case the sequence of events might be this:

| Photon polarization |

At BS1 |

At BS2 |

Final result |

| Up (+) |

Photon is reflected |

Photon is transmitted |

Photon goes to D1 |

| Down (–) |

Photon is transmitted |

Photon is reflected |

Photon goes to D1 |

This is a nice symmetrical explanation that does not involve any quantum-mechanical weirdness. The problem is: it cannot work. Why not? What happens if we block one of the two paths? For example, let us block the lower path in the setup where all photons went to D0. We know – from experiment – that the outcome will be the following:

| Final result |

Probability |

| Photon is absorbed at the block |

0.50 |

| Photon goes to D0 |

0.25 |

| Photon goes to D1 |

0.25 |

How is this possible? Before blocking the lower path, no photon went to D1. They all went to D0. If our hidden variable theory was correct, the photons that do not get absorbed should also go to D0, as shown below.

| Photon polarization |

At BS1 |

At BS2 |

Final result |

| Up (+) |

Photon is reflected |

Photon is reflected |

Photon goes to D0 |

| Down (–) |

Photon is absorbed |

Photon was absorbed |

Photon was absorbed |

Conclusion

Our hidden variable theory does not work. Physical or geometric interpretations of the wavefunction are nice, but they do not explain quantum-mechanical interference. Their value is, therefore, didactic only.

Jean Louis Van Belle, 2 November 2018

References

This paper discusses general principles in physics only. Hence, references were limited to references to general textbooks and courses and physics textbooks only. The two key references here are the MIT introductory course on quantum physics and Feynman’s Lectures – both of which can be consulted online. Additional references to other material are given in the text itself (see footnotes).

[1] Duns Scotus, Commentaria.

[2] See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam%27s_razor.

[3] Feynman’s Lectures on Quantum Mechanics, Vol. III, Chapter 5, Section 5.

[4] See, for example, the MIT’s edX Course 8.04.1x (Quantum Physics), Lecture Notes, Chapter 4, Section 3.

[5] Photons are spin-one particles but they do not have a spin-zero state.

[6] Of course, the formulas only give the elementary wavefunction. The wave packet will be a Fourier sum of such functions.

[7] See, for example, https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/physics/staff/academic/mhadley/explanation/spin/, accessed on 30 October 2018

[8] Feynman’s Lectures on Quantum Mechanics, Vol. III, Chapter 6, Section 3.

[9] Jean Louis Van Belle, Euler’s wavefunction (http://vixra.org/abs/1810.0339, accessed on 30 October 2018)

[10] See: MIT edX Course 8.04.1x (Quantum Physics), Lecture Notes, Chapter 1, Section 3 (Loss of determinism).

[11] The z-direction is the direction of wave propagation in this example. In quantum mechanics, we often define the direction of wave propagation as the x-direction. This will, hopefully, not confuse the reader. The choice of axes is usually clear from the context.

[12] Source of the illustration: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/71/Sine_cosine_one_period.svg..

[13] Classical theory assumes an atomic or molecular system will absorb a photon and, therefore, be in an excited state (with higher energy). The atomic or molecular system then goes back into its ground state by emitting another photon with the same energy. Hence, we should probably not think in terms of a specific photon getting through.

[14] Feynman’s Lectures on Quantum Mechanics, Vol. III, Chapter 1, Section 1.

[15] Source of the illustration: MIT edX Course 8.04.1x (Quantum Physics), Lecture Notes, Chapter 1, Section 4 (Quantum Superpositions).