Pre-scriptum (dated 26 June 2020): In pre-scriptums for my previous posts on math, I wrote that the material in posts like this remains interesting but that one, strictly speaking, does not need it to understand quantum mechanics. This post is a little bit different: one has to understand the basic concept of a differential equation as well as the basic solution methods. So, yes, it is a prerequisite.

Original post:

According to the ‘What’s Physics All About?’ title in Usborne Children’s Books series, physics is all about ‘discovering why things fall to the ground, how sound travels through walls and how many wonderful inventions exist thanks to physics.’

The Encyclopædia Britannica rephrases that definition of physics somewhat and identifies physics with ‘the science that deals with the structure of matter and the interactions between the fundamental constituents of the observable universe.’

[…]

Now, if I would have to define physics at this very moment, I’d say that physics is all about solving differential equations and complex integration. Let’s be honest: is there any page in any physics textbook that does not have any ∫ or ∂ symbols on it?

When everything is said and done, I guess that’s the Big Lie behind all these popular books, including Penrose’s Road to Reality. You need to learn how to write and speak in the language of physics to appreciate them and, for all practical purposes, the language of physics is math. Period.

I am also painfully aware of the fact that the type of differential equations I had to study as a student in economics (even at the graduate or Master’s level) are just a tiny fraction of what’s out there. The variety of differential equations that can be solved is truly intimidating and, because each and every type comes with its own step-by-step methodology, it’s not easy to remember what needs to be done.

Worse, I actually find it quite difficult to remember what ‘type’ this or that equation actually is. In addition, one often needs to reduce or rationalize the equation or – more complicated – substitute variables to get the equation in a form which can then be used to apply a certain method. To top if all off, there’s also this intimidating fact that – despite all these mathematical acrobatics – the vast majority of differential equations can actually not be solved analytically. Hence, in order to penetrate that area of darkness, one has to resort to numerical approaches, which I have yet to learn (the oldest of such numerical methods was apparently invented by the great Leonhard Euler, an 18th century mathematician and physicist from Switzerland).

So where am I actually in this mathematical Wonderland?

I’ve looked at ordinary differential equations only so far, i.e. equations involving one dependent variable (usually written as y) and one independent variable (usually written as x or t), and at equations of the first order only. So that means that (a) we don’t have any ∂ symbols in these differential equations (let me use the DE abbreviation from now on) but just the differential symbol d (so that’s what makes them ordinary DEs, as opposed to partial DEs), and that (b) the highest-order derivative in them is the first derivative only (i.e. y’ = dy/dx). Hence, the only ‘lower-order derivative’ is the function y itself (remember that there’s this somewhat odd mathematical ‘convention’ identifying a function with the zeroth derivative of itself).

Such first-order DEs will usually not be linear things and, even if they look like linear things, don’t jump to conclusions because the term linear (first-order) differential equation is very specific: it means that the (first) derivative and the function itself appear in a linear combination. To be more specific, the term linear differential equation (for the first-order case) is reserved for DEs of the form

a1(t) y'(t) + a0(t) y(t) = q(t).

So, besides y(t) and y'(t) – whose functional form we don’t know because (don’t forget!) finding y(t) is the objective of solving these DEs 🙂 – we have three other random functions of the independent variable t here, namely a1(t), a0(t) and q(t). Now, these functions may or may not be linear functions of t (they’re probably not) but that doesn’t matter: the important thing – to qualify as ‘linear’ – is that (1) y(t) and y'(t), i.e. the dependent variable and its derivative, appear in a linear combination and have these ‘coefficients’ a1(t) and a0(t) (which, I repeat, may be constants but, more likely, will probably be functions of t themselves), and (2) that, on the other side of the equation, we’ve got this q(t) function, which also may or – more likely – may not be a constant.

Are you still with me? [If not, read again. :-)]

This type of equation – of which the example in my previous post was a specimen – can be solved by introducing a so-called integrating factor. Now, I won’t explain that here – not because the explanation is too easy (it’s not), but because it’s pretty standard and, much more importantly, because it’s too lengthy to copy here. [If you’d be looking for an ‘easy’ explanation, I’d recommend Paul’s Online Math Notes once again.]

So I’ll continue with my ‘typology’ of first-order DEs. However, I’ll do so only after noting that, before letting that integrating factor loose (OK, let me say something about it: in essence, the integrating factor is some function λ(x) which we’ll multiply with the whole equation and which, because of a clever choice of λ(x) obviously, helps us to solve the equation), you’ll have to rewrite these linear first-order DEs as y'(t) + (a0(t)/a1(t)) y(t) = q(t)/a1(t) (so just divide both sides by this a1(t) function) or, using the more prevalent notation x for the independent variable (instead of t) and equating a0(x)/a1(x) with F(x) and q(x)/a1(x) with G(x), as:

dy/dx + F(x) y = G(x), or y‘ + F(x) y = G(x)

So, that’s one ‘type’ of first-order differential equations: linear DEs. [We’re only dealing with first-order DEs here but let me note that the general form of a linear DE of the nth order is an(x) y(n) + an-1(x) y(n-1) + … + a1(x) y’ + a0(x) y = q(x), and that most standard texts on higher-order DEs focus on linear DEs only, so they are important – even if they are only a tiny fraction of the DE universe.]

The second major ‘exam-type’ of DEs which you’ll encounter is the category of so-called separable DEs. Separable (first-order) differential equations are equations of the form:

P(x) dx + Q(y) dy = 0, which can also be written as G(y) y‘ = F(x)

or dy/dx = F(x)/G(y)

The notion of ‘separable’ refers to the fact that we can neatly separate out the terms involving y and x respectively, in order to then bring them on the left- and right-hand side of the equation respectively (cf. the G(y) y‘ = F(x) form), which is what we’ll need to do to solve the equation.

I’ve been rather vague on that ‘integrating factor’ we use to solve linear equations – for the obvious reason that it’s not all that simple – but, in contrast, solving separable equations is very straightforward. We don’t need to use an integrating factor or substitute something. We actually don’t need any mathematical acrobatics here at all! We can just ‘separate’ the variables indeed and integrate both sides.

Indeed, if we write the equation as G(y)y’ = G(y)[dy/dx] = F(x), we can integrate both sides over x, but use the fact that ∫G(y)[dy/dx]dx = ∫G(y)dy. So the equation becomes ∫G(y)dy = ∫F(x)dx, and so we’re actually integrating a function of y over y on the left-hand side, and the other function (of x), on the right-hand side, over x. We then get an implicit function with y and x as variables and, usually, we can solve that implicit equation and find y in terms of x (i.e. we can solve the implicit equation for y(x) – which is the solution for our problem). [I do say ‘usually’ here. That means: not always. In fact, for most implicit functions, there’s no formula which defines them explicitly. But that’s OK and I won’t dwell on that.]

So that’s what meant with ‘separation’ of variables: we put all the things with y on one side, and all the things with x on the other, and then we integrate both sides. Sort of. 🙂

OK. You’re with me. In fact, you’re ahead of me and you’ll say: Hey! Hold it! P(x)dx + Q(y)dy is a linear combination as well, isn’t it? So we can look at this as a linear DE as well, isn’t it? And so why wouldn’t we use the other method – the one with that factor thing?

Well… No. Go back and read again. We’ve got a linear combination of the differentials dx and dy here, but so that’s obviously not a linear combination of the derivative y’ and the function y. In addition, the coefficient in front of dy is a function in y, i.e. a function of the dependent variable, not a function in x, so it’s not like these an(x) coefficients which we would need to see in order to qualify the DE as a linear one. So it’s not linear. It’s separable. Period.

[…] Oh. I see. But are these non-linear things allowed really?

Of course. Linear differential equations are only a tiny little fraction of the DE universe: first, we can have these ‘coefficients’, which can be – and usually will be – a function of both x and y, and then, secondly, the various terms in the DE do not need to constitute a nice linear combination. In short, most DEs are not linear – in the context-specific definitional sense of the word ‘linear’ that is (sorry for my poor English). 🙂

[…] OK. Got it. Please carry on.

That brings us to the third type of first-order DEs: these are the so-called exact DEs. Exact DEs have the same ‘shape’ as separable equations but the ‘coefficients’ of the dx and dy terms are a function of both x and y indeed. In other words, we can write them as:

P(x, y) dx + Q(x, y) dy = 0, or as A(x, y) dx + B(x, y) dy = 0,

or, as you will also see it, dy/dx = M(x, y)/N(x, y) (use whatever letter you want).

However, in order to solve this type of equation, an additional condition will need to be fulfilled, and that is that ∂P/∂y = ∂Q/∂x (or ∂A/∂y = ∂B/∂x if you use the other representation). Indeed, if that condition is fulfilled – which you have to verify by checking these derivatives for the case at hand – then this equation is a so-called exact equation and, then… Well… Then we can find some function U(x, y) of which P(x, y) and Q(x, y) are the partial derivatives, so we’ll have that ∂U(x, y)/∂x = P(x, y) and ∂U(x, y)/∂y = Q(x, y). [As for that condition we need to impose, that’s quite logical if you write down the second-order cross-partials, ∂P(x, y)/∂y and ∂Q(x, y)/∂x and remember that such cross-partials are equal to each other, i.e. Uxy = Uyx.]

We can then find U(x, y), of course, by integrating P or Q. And then we just write that dU = P(x, y) dx + Q(x, y) dy = Ux dx + Uy dy = 0 and, because we’ve got the functional form of U, we’ll get, once again, an implicit function in y and x, which we may or may not be able to solve for y(x).

Are you still with me? [If not, read again. :-)]

So, we’ve got three different types of first-order DEs here: linear, separable, and exact. Are there any other types? Well… Yes.

Yes of course! Just write down any random equation with a first-order derivative in it – don’t think: just do it – and then look at what you’ve jotted down and compare its form with the form of the equations above: the probability that it will not fit into any of the three mentioned categories is ‘rather high’, as the Brits would say – euphemistically. 🙂

That being said, it’s also quite probable that a good substitution of the variable could make it ‘fit’. In addition, we have not exhausted our typology of first-order DEs as yet and, hence, we’ve not exhausted our repertoire of methods to solve them either.

For example, if we would find that the conditions for exactness for the equation P(x, y) dx + Q(x, y) dy = 0 are not fulfilled, we could still solve that equation if another condition would turn out to be true: if the functions P(x, y) and Q(x, y) would happen to be homogeneous, i.e. P(x, y) and Q(x, y) would both happen to satisfy the equality P(ax, ay) = ar P(x, y) and Q(ax, ay) = ar Q(x, y) (i.e. they are both homogeneous functions of degree r), then we can use the substitution v(x) = y/x (i.e. y = vx) and transform the equation into a separable one, which we can then solve for v.

Indeed, the substitution yields dv/dx = [F(v)-v]/x, and so that’s nicely separable. We can then find y, after we’ve solved the equation, by substituting v for y/x again. I’ll refer to the Wikipedia article on homogeneous functions for the proof that, if P(x, y) and Q(x, y) are homogeneous indeed, we can write the differential equation as:

dy/dx = M(x, y)/N(x, y) = F(y/x) or, in short, y’ = F(y/x)

[…]

Hmm… OK. What’s next? That condition of homogeneity which we are imposing here is quite restrictive too, isn’t it?

It is: the vast majority of M(x, y) and N(x, y) functions will not be homogeneous and so then we’re stuck once again. But don’t worry, the mathematician’s repertoire of substitutions is vast, and so there’s plenty of other stuff out there which we can try – if we’d remember it at least 🙂 .

Indeed, another nice example of a type of equation which can be made separable through the use of a substitution are equations of the form y’ = G(ax + by), which can be rewritten as a separable equation by substituting ax + by for v. If we do this substitution, we can then rewrite the equation – after some re-arranging of the terms at least – as dv/dx = a + b G(v), and so that’s, once again, an equation which is separable and, hence, solvable. Tick! 🙂

Finally, we can also solve DEs which come in the form of a so-called Bernoulli equation through another clever substitution. A Bernoulli equation is a non-linear differential equation in the form:

y’ + F(x) y = G(x) yn

The problem here is, obviously, that exponent n in the right-hand side of the equation (i.e. the exponent of y), which makes the equation very non-linear indeed. However, it turns out that, if one substitutes y for v = y1-n, we are back at the linear situation and so we can then use the method for the linear case (i.e. the use of an integrating factor). [If you want to try this without consulting a math textbook, then don’t forget that v’ will be equal to v’ = (1-n)y-ny’ (so y-ny’ = v’/(1-n), and also that you’ll need to rewrite the equation as y-ny’ + f(x) y1-n = g(x) before doing that substitution. Of course, also remember that, after the substitution, you’ll still have to solve the linear equation, so then you need to know how to use that integrating factor. Good luck! :-)]

OK. I understand you’ve had enough by now. So what’s next? Well, frankly, this is not so bad as far as first-order differential equations go. I actually covered a lot of terrain here, although Mathews and Walker go much and much further (so don’t worry: I know what to do in the days ahead!).

The thing now is to get good at solving these things, and to understand how to model physical systems using such equations. But so that’s something which is supposed to be fun: it should be all about “discovering why things fall to the ground, how sound travels through walls and how many wonderful inventions exist thanks to physics” indeed.

Too bad that, in order to do that, one has to do quite some detour!

Post Scriptum: The term ‘homogeneous’ is quite confusing: there is also the concept of linear homogeneous differential equations and it’s not the same thing as a homogeneous first-order differential equation. I find it one of the most striking examples of how the same word can mean entirely different things even in mathematics. What’s the difference?

Well… A homogeneous first-order DE is actually not linear. See above: a homogeneous first-order DE is an equation in the form dy/dx = M(x, y)/N(x, y). In addition, there’s another requirement, which is as important as the form of the DE, and that is that M(x, y) and N(x, y) should be homogeneous functions, i.e. they should have that F(ax, ay) = ar F(x, y) property. In contrast, a linear homogeneous DE is, in the first place, a linear DE, so it’s general form must be L(y) = an(x) y(n) + an-1(x) y(n-1) + … + a1(x) y’ + a0(x) y = q(x) (so L(y) must be a linear combination whose terms have coefficients which may be constants but, more often than not, will be functions of the variable x). In addition, it must be homogeneous, and this means – in this context at least – that q(x) is equal to zero (so q(x) is equal to the constant 0). So we’ve got L(y) = 0 or, if we’d use the y’ + F(x) y = G(x) formulation, we have y’ + F(x) y = 0 (so that G(x) function in the more general form of a linear first-order DE is equal to zero).

So is this yet another type of differential equation? No. A linear homogeneous DE is, in the first place, linear, 🙂 so we can solve it with that method I mentioned above already, i.e. we should introduce an integrating factor. An integrating factor is a new function λ(x), which helps us – after we’ve multiplied the whole equation with this λ(x) – to solve the equation. However, while the procedure is not difficult at all, its explanation is rather lengthy and, hence, I’ll skip that and just refer my imaginary readers here to the Web.

But, now that we’re here, let me quickly complete my typology of first-order DEs and introduce a generalization of the (first) notion of homogeneity, and that’s isobaric differential equations.

An isobaric DE is an equation which has the same general form as the homogeneous (first-order) DE, so an isobaric DE looks like dy/dx = F(x, y), but we have a more general condition than homogeneity applying to F(x, y), namely the property of isobarity (which is another word with multiple meanings but let us not be bothered by that). An isobaric function F(x, y) satisfies the following equality: F(ax, ary) = ar-1F(x, y), and it can be shown that the isobaric differential equation dy/dx = F(x, y), i.e. a DE of this form with F(x, y) being isobaric, becomes separable when using the y = vxr substitution.

OK. You’ll say: So what? Well… Nothing much I guess. 🙂

Let me wrap up by noting that we also have the so-called Clairaut equations as yet another type of first-order DEs. Clairaut equations are first-order DEs in the form y – xy’ = F(y’). When we differentiate both sides, we get y”(F'(y’) + x) = 0.

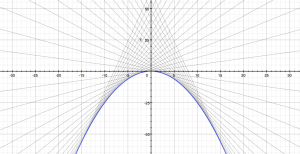

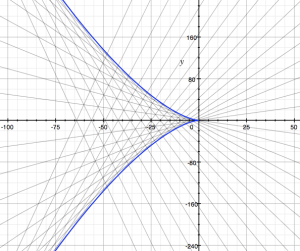

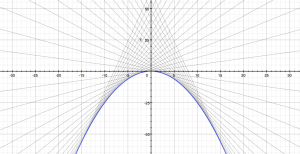

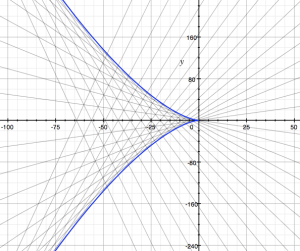

Now, this equation holds if (i) y” = 0 or (ii) F'(y’) + x = 0 (or both obviously). Solving (i), so solving for y” = 0, yields a family of (infinitely many) straight-line functions y = ax + b as the general solution, while solving (ii) yields only one solution, the so-called singular solution, whose graph is the envelope of the graphs of the general solution. The graph below shows these solutions for the square and cube functional forms respectively (so the solutions for y – xy’ = [y’]2 and y – xy’ = [y’]3 respectively).

For the F(y’) = [y’]2 functional form, you have a parabola (i.e. the graph of a quadratic function indeed) as the envelope of all of the straight lines. As for the F(y’) = [y’]3 function, well… I am not sure. It reminds me of those plastic French curves we used as little kids to make all kinds of silly drawings. It also reminds me of those drawings we had to make in high school on engineering graph paper using an expensive 0.1 or 0.05 mm pen. 🙂

In any case, we’ve got quite a collection of first-order DEs now – linear, separable, exact, homogeneous, Bernouilli-type, isobaric, Clairaut-type, … – and so I think I should really stop now. Remember I haven’t started talking about higher-order DEs (e.g. second-order DEs) as yet, and I haven’t talked about partial differential equations either, and so you can imagine that the universe of differential equations is much and much larger than what this brief overview here suggests. Expect much more to come as I’ll dig into it!

Post Scriptum 2: There is a second thing I wanted to jot down somewhere, and this post may be the appropriate place. Let me ask you something: have you never wondered why the same long S symbol (i.e. the summation or integration symbol ∫) is used to denote both definite and indefinite integrals? I did. I mean the following: when we write ∫f(x)dx or ∫[a, b] f(x)dx, we refer to two very different things, don’t we? Things that, at first sight, have nothing to do with each other.

Huh?

Well… Think about it. When we write ∫f(x)dx, then we actually refer to infinitely many functions F1(x), F2(x), F3(x), etcetera (we generally write them as F(x) + c, because they differ by a constant only) which all belong to the same ‘family’ because they all have the same derivative, namely that function f(x) in the integrand. So we have F1‘(x) = F2‘(x) = F3‘(x) = … = F'(x) = f(x). The graphs of these functions cover the whole plane, and we can say all kinds of things about them, but it is not obvious that these functions can be related to some sum, finite or infinite. Indeed, when we look for those functions by solving, for example, an integral such as ∫(xe6x+x5/3+√x)dx, we use a lot of rules and various properties of functions (this one will involve integration by parts for example) but nothing of that reminds us, not even remotely, of doing some kind of finite or infinite sum.

On the other hand, ∫[a, b] f(x)dx, i.e. the definite integral of f(x) over the interval [a, b], yields a real number with a very specific meaning: it’s the area between point a and point b under the graph y = f(x), and the long S symbol (i.e. the summation symbol ∫) is particularly appropriate because the expression ∫[a, b] f(x)dx stands for an infinite sum indeed. That’s why Leibniz chose the symbol back in 1675!

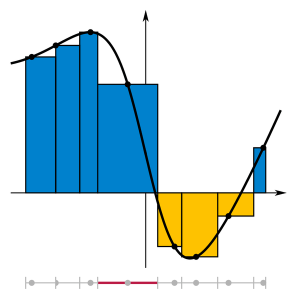

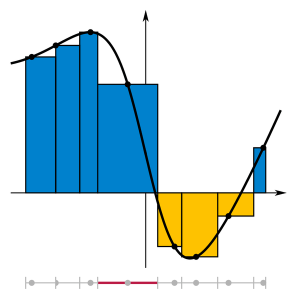

Let me give an example here. Let x be the distance which an object has traveled since we started observing it. Now, that distance is equal to an infinite sum which we can write as ∑v(t)Δt, . What we do here amounts to multiplying the speed v at time t, i.e. v(t), with (the length of) the time interval Δt over an infinite number of little time intervals, and then we sum all those products to get the total distance. If we use the differential notation (d) for infinitesimally small quantities (dv, dx, dt etcetera), then this distance x will be equal to the sum of all little distances dx = v(t)dt. So we have an infinite sum indeed which, using the long S (i.e. Leibniz’s summation symbol), we can write as ∑v(t)dt = ∑dx = ∫[0, t]v(t)dt = ∫[0, t]dx = x(t).

The illustration below gives an idea of how this works. The black curve is the v(t) function, so velocity (vertical axis) as a function of time (horizontal axis). Don’t worry about the function going negative: negative velocity would mean that we allow our object to reverse direction. As you can see, the value of v(t) is the (approximate) height of each of these rectangles (note that we take irregular partitions here, but that doesn’t matter), and then just imagine that the time intervals Δt (i.e. the width of the rectangular areas) become smaller and smaller – infinitesimally small in fact.

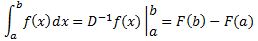

I guess I don’t need to be more explicit here. The point is that we have such infinite sum interpretation for the definite integral only, not for an indefinite one. So why would we use the same summation symbol ∫ for the indefinite integral? Why wouldn’t we use some other symbol for it (because it is something else, isn’t it?)? Or, if we wouldn’t want to introduce any new symbols (because we’ve got quite a bunch already here), then why wouldn’t we combine the common inverse function symbol (i.e. f-1) and the differentiation operator D, Dx or d/dx, so we would write D-1f(x) or Dx-1 instead of ∫f(x)dx? If we would do that, we would write the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, which you obviously know (as you need it to solve definite integrals), as:

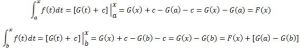

You have seen this formula, haven’t you? Except for the D-1f(x) notation of course. This Theorem tells us that, to solve the definite integral on the left-hand side, we should just (i) take an antiderivative of f(x) (and it really doesn’t matter which one because the constant c will appear two times in the F(b) – F(a) equation, as c — c = 0 to be precise, and, hence, this constant just vanishes, regardless of its value), (ii) plug in the values a and b, (iii) subtract one from the other (i.e. F(a) from F(b), not the other way around—otherwise we’ll have the sign of the integral wrong), and there we are: we’ve got the answer—for our definite integral that is.

But so I am not using the standard ∫ symbol for the antiderivative above. I am using… well… a new symbol, D-1, which, in my view, makes it clear what we have to do, and that is to find an antiderivative of f(x) so we can solve that definite integral. [Note that, if we’d want to keep track of what variable we’re integrating over (in case we’d be dealing with partial differential equations for instance, or if it would not be sufficiently clear from the context), we should use the Dx-1 notation, rather than just D.]

OK. You may think this is hairsplitting. What’s in a name after all? Or in a symbol in this case? Well… In math, you need to make sure that your notations make perfect sense and that you don’t write things that may be confusing.

That being said, there’s actually a very good reason to re-use the long S symbol for indefinite integrals also.

Huh? Why? You just said the definite and indefinite integral are two very different things and so that’s why you’d rather see that new D-1f(x) notation instead of ∫f(x)dx !?

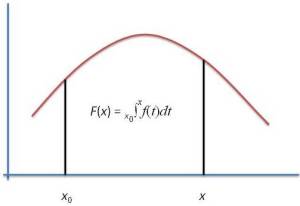

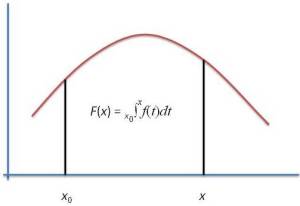

Well… Yes and no. You may or may not remember from your high school course in calculus or analysis that, in order to get to that fundamental theorem of calculus, we need the following ‘intermediate’ result: IF we define a function F(x) in some interval [a, b] as F(x) = ∫[a, x] f(t)dt (so a ≤ x ≤ b and a ≤ t ≤ x) — so, in other words, we’ve got a definite integral here with some fixed value a as the lower boundary but with the variable x itself as the upper boundary (so we have x instead of the fixed value b, and b now only serves as the upper limit of the interval over which we’re defining this new function F(x) here) — THEN it’s easy to show that the derivative of this F(x) function will be equal to f(x), so we’ll find that F'(x) = f(x).

In other words, F(x) = ∫[a, x] f(t)dt is, quite obviously, one of the (infinitely many) antiderivatives of f(x), and if you’d wonder which one, well… That obviously depends on the value of a that we’d be picking. So there actually is a pretty straightforward relationship between the definite and indefinite integral: we can find an antiderivative F(x) + c of a function f(x) by evaluating a definite integral from some fixed point a to the variable x itself, as illustrated below.

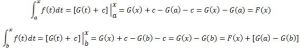

Now, remember that we just need one antiderivative to solve a definite integral, not the whole family, and which one we’ll get will depend on that value a (or x0as that fixed point is being referred to in the formula used the illustration above), so it will depend on what choice we make there for the lower boundary. Indeed, you can work that out for yourself by just solving ∫[x0, x] f(t)dt for two different values of x0 (i.e. a and b in the example below):

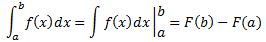

The point is that we can get all of the antiderivatives of f(x) through that definite integral: it just depends on a judicious choice of x0 but so you’ll get the same family of functions F(x) + c. Hence, it is logical to use the same summation symbol, but with no bounds mentioned, to designate the whole family of antiderivatives. So, writing the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus as

instead of that alternative with the D-1f(x) notation does make sense. 🙂

Let me wrap up this conversation by noting that the above-mentioned ‘intermediate’ result (I mean F(x) = ∫[a, x] f(t)dt with F'(x) = f(x) here) is actually not ‘intermediate’ at all: it is equivalent to the fundamental theorem of calculus itself (indeed, the author of the Wikipedia article of the fundamental theorem of calculus presents the expression above as a ‘corollary’ to the F(x) = ∫[a, x] f(t)dt result, which he or she presents as the theorem itself). So, if you’ve been able to prove the ‘intermediate’ result, you’ve also proved the theorem itself. One can easily see that by verifying the identities below:

Huh? Is this legal? It is. Just jot down a graph with some function f(t) and the values a, x and b, and you’ll see it all makes sense. 🙂