Note: A few years after writing the post below, I published a paper on the anomalous magnetic moment which makes (some of) what is written below irrelevant. It gives a clean classical explanation for it. Have a look by clicking on the link here !

Original blog post:

Feynman starts his Volume of Lectures on quantum mechanics (so that’s Volume III of the whole series) with the rules we already know, so that’s the ‘special’ math involving probability amplitudes, rather than probabilities. However, these introductory chapters assume theoretical zero-spin particles, which means they don’t have any angular momentum. While that makes it much easier to understand the basics of quantum math, real elementary particles do have angular momentum, which makes the analysis much more complicated. Therefore, Feynman makes it very clear, after his introductory chapters, that he expects all prospective readers of his third volume to first work their way through chapter 34 and 35 of the second volume, which discusses the angular momentum of elementary particles from both a classical as well as a quantum-mechanical perspective. So that’s what we will do here. I have to warn you, though: while the mentioned two chapters are more generous with text than other textbooks on quantum mechanics I’ve looked at, the matter is still quite hard to digest. By way of introduction, Feynman writes the following:

“The behavior of matter on a small scale—as we have remarked many times—is different from anything that you are used to and is very strange indeed. Understanding of these matters comes very slowly, if at all. One never gets a comfortable feeling that these quantum-mechanical rules are ‘natural’. Of course they are, but they are not natural to our own experience at an ordinary level. The attitude that we are going to take with regard to this rule about angular momentum is quite different from many of the other things we have talked about. We are not going to try to ‘explain’ it but tell you what happens.”

I personally feel it’s not all as mysterious as Feynman claims it to be, but I’ll let you judge for yourself. So let’s just go for it and see what comes out. 🙂

Atomic magnets and the g-factor

When discussing electromagnetic radiation, we introduced the concept of atomic oscillators. It was a very useful model to help us understand what’s supposed to be going on. Now we’re going to introduce atomic magnets. It is based on the classical idea of an electron orbiting around a proton. Of course, we know this classical idea is wrong: we don’t have nice circular electron orbitals, and our discussion on the radius of an the electron in our previous post makes it clear that the idea of the electron itself is rather fuzzy. Nevertheless, the classical concepts used to analyze rotation are also used, mutatis mutandis, in quantum mechanics. Mutatis mutandis means: with necessary alterations. So… Well… Let’s go for it. 🙂 The basic idea is the following: an electron in a circular orbit is a circular current and, hence, it causes a magnetic field, i.e. a magnetic flux through the area of the loop—as illustrated below.

As such, we’ll have a magnetic (dipole) moment, and you may want to review my post(s) on that topic so as to ensure you understand what follows. The magnetic moment (μ) is the product of the current (I) and the area of the loop (π·r2), and its conventional direction is given by the μ vector in the illustration below, which also shows the other relevant scalar and/or vector quantities, such as the velocity v and the orbital angular momentum J. The orbital angular momentum is to be distinguished from the spin angular momentum, which results from the spin around its own axis. So the spin angular momentum – which is often referred to as the spin tout court – is not depicted below, and will only be discussed in a few minutes.

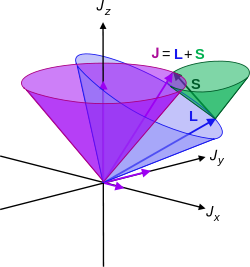

Let me interject something on notation here. Feynman’s always uses J, for whatever momentum. That’s not so usual. Indeed, if you’d google a bit, you’ll see the convention is to use S and L respectively to distinguish spin and orbital angular momentum respectively. If we’d use S and L, we can write the total angular momentum as J = S + L, and the illustration below shows how the S and L vectors are to be added. It looks a bit complicated, so you can skip this for now and come back to it later. But just try to visualize things:

- The L vector is moving around, so that assumes the orbital plane is moving around too. That happens when we’d put our atomic system in a magnetic field. We’ll come back to that. In what follows, we’ll assume the orbital plane is not moving.

- The S vector here is also moving, which also assumes the axis of rotation is not steady. What’s going on here is referred to as precession, and we discussed it when presenting the math one needs to understand gyroscopes.

- Adding S and L yields J, the total angular momentum. Unsurprisingly, this vector wiggles around too. Don’t worry about the magnitudes of the vectors here. Also, in case you’d wonder why the axis of symmetry for the movement of the J vector happens to be the Jz axis, the answer is simple: we chose the coordinate system so as to ensure that was the case.

But I am digressing. I just inserted the illustration above to give you an inkling of where we’re going with this. Indeed, what’s shown above will make it easier for you to see how we can generalize the analysis that we’ll do now, which is an analysis of the orbital angular momentum and the related magnetic moment only. Let me copy the illustration we started with once more, so you don’t have to scroll up to see what we’re talking about.

So we have a charge orbiting around some center. It’s a classical analysis, and so it’s really like a planet around the Sun, except that we should remember that likes repel, and opposites attract, so we’ve got a minus sign in the force law here.

Let’s go through the math. The magnetic moment is the current times the area of the loop. As the velocity is constant, the current is just the charge q times the frequency of rotation. The frequency of rotation is, of course, the velocity (i.e. the distance traveled per second) divided by the circumference of the orbit (i.e. 2π·r). Hence, we write: I = (qe·v)/(2π·r) and, therefore: μ = (qe/·v)·π·r2)/(2π·r) = qe·v·r/2. Note that, as per the convention, current is defined as a flow of positive charges, so the illustration above actually assumes we’re talking some proton in orbit, so q = qe would be the elementary charge +1. If we’d be talking an electron, then its charge is to be denoted as –qe (minus qe, i.e. −1), and we’d need to reverse the direction of μ, which we’ll do in a moment. However, to simplify the discussion, you should just think of some positive charge orbiting the way it does in the illustration above.

OK. That’s all there’s to say about the magnetic moment—for the time being, that is. Let’s think about the angular momentum now. It’s orbital angular momentum here, and so that’s the type of angular momentum we discussed in our post on gyroscopes. We denoted it as L indeed – i.e. not as J, but that’s just a matter of conventions – and we noted that L could be calculated as the vector cross product of the position vector r and the momentum vector p, as shown in the animation below, which also shows the torque vector τ.

The angular momentum L changes in the animation above. In our J case above, it doesn’t. Also, unlike what’s happening with the angular momentum of that swinging ball above, the magnitude of our J doesn’t change. It remains constant, and it’s equal to |J| = J = |r×p| = |r|·|p|·sinθ = r·p = r·m·v. One should note this is a non-relativistic formula, but as the relative velocity of an electron v/c is equal to the fine-structure constant, so that’s α ≈ 0.0073 (see my post on the fine-structure constant if you wonder where this formula comes from), it’s OK to not include the Lorentz factor in our formulas as for now.

Now, as I mentioned already, the illustration we’re using to explain μ and J is somewhat unreal because it assumes a positive charge q, and so μ and J point in the same direction in this case, which is not the case if we’d be talking an actual atomic system with an electron orbiting around a proton. But let’s go along with it as for now and so we’ll put the required minus sign in later. We can combine the J = r·m·v and μ = q·v·r/2 formulas to write:

μ = (q/2m)·J or μ/J = (q/2m) (electron orbit)

In other words, the ratio of the magnetic moment and the angular moment depends on (1) the charge (q) and (2) the mass of the charge, and on those two variables only. So the ratio does not depend on the velocity v nor on the radius r. It can be noted that the q/2m factor is often referred to as the gyromagnetic factor (not to be confused with the g-factor, which we’ll introduce shortly). It’s good to do a quick dimensional check of this relation: the magnetic moment is expressed in ampère per second times the loop area, so that’s (C/s)·m2. On the right-hand side, we have the dimension of the gyromagnetic factor, which is C/kg, times the dimension of the angular momentum, which is m·kg·m/s, so we have the same units on both sides: C·m2/s, which is often written as joule per tesla (J/T): the joule is the energy unit (1 J = 1 N·m), and the tesla measures the strength of the magnetic field (1 T = 1 (N·s)/(C·m). OK. So that works out.

So far, so good. The story is a little bit different for the spin angular momentum and the spin magnetic moment. The formula is the following:

μ = (q/m)·J (electron spin)

This formula says that the μ/J ratio is twice what it is for the orbital motion of the electron. Why is that? Feynman says “the reasons are pure quantum-mechanical—there is no classical explanation.” So I’d suggest we just leave that question open for the moment and see if we’re any wiser once we’ve worked ourselves through all of his Lectures on quantum physics. 🙂 Let’s just go along with it as for now.

Now, we can write both formulas – i.e. the formula for the spin and the orbital angular momentum – in a more general way using the format below:

μ = –g·(qe/2me)·J

Why the minus sign? Well… I wanted to get the sign right this time. Our model assumed some positive charge in orbit, but so we want a formula for a atomic system, and so our circling charge should be an electron. So the formula above is the formula for a electron, and the direction of the magnetic moment and of the angular motion will be opposite for electrons: it just replaces q by –qe. The format above also applies to any atomic system: as Feynman writes, “For an isolated atom, the direction of the magnetic moment will always be exactly opposite to the direction of the angular momentum.” So the g-factor will be characteristic of the state of the atom. It will be 1 for a pure orbital moment, 2 for a pure spin moment, or some other number in-between for a complicated system like an atom, indeed.

You may have one last question: why qe/2m instead of qe/m in the middle? Well… If we’d take qe/m, then g would be 1/2 for the orbital angular momentum, and the initial idea with g was that it would be some integer (we’ll quickly see that’s an idea only). So… Well… It’s just one more convention. Of course, conventions are not always respected so sometimes you’ll see the expression above written without the minus sign, so you may see it as μ = g·(qe/2me)·J. In that case, the g-factor for our example involving the spin angular momentum and the spin magnetic moment, will obviously have to be written as minus 2.

Of course, it’s easy to see that the formula for the spin of a proton will look the same, except that we should take the mass of the proton in the formula, so that’s mp instead of me. Having said that, the elementary charge remains what it is, but so we write it without the minus sign here. To make a long story short, the formula for the proton is:

μ = g·(qe/2mp)·J

OK. That’s clear enough. For electrons, the g-factor is referred to as the Landé g-factor, while the g-factor for protons or, more generally, for any spinning nucleus, is referred to as the nuclear g-factor. Now, you may or may not be surprised, but there’s a g-factor for neutrons too, despite the fact that they do not carry a net charge: the explanation for it must have something to do with the quarks that make up the neutron but that’s a complicated matter which we will not get into here. Finally, there is a g-factor for a whole atom, or a whole atomic system, and that’s referred to as… Well… Just the g-factor. 🙂 It’s, obviously, a number that’s characteristic of the state of the atom.

So… This was a big step forward. We’ve got all of the basics on that ‘magical’ spin number here, and so I hope it’s somewhat less ‘magical’ now. 🙂 Let me just copy the values of the g-factor for some elementary particles. It also shows how hard physicists have been trying to narrow down the uncertainty in the measurement. Quite impressive! The table comes from the Wikipedia article on it. I hope the explanations above will now enable you to read and understand that. 🙂

Let’s now move on to the next topic.

Spin numbers and states

Of course, we’re talking quantum mechanics and, therefore, J can only take on a finite number of values. While that’s weird – as weird as other quantum-mechanical things, such as the boson-fermion math, for example – it should not surprise us. As we will see in a moment, the values of J will determine the magnetic energy our system will acquire when we put in some magnetic field and, as Feynman writes: “That the energy of an atom in the magnetic field can have only certain discrete energies is really not more surprising than the fact that atoms in general have only certain discrete energy levels. Why should the same thing not hold for atoms in a magnetic field? It does. It is just correlation of this with the idea of an oriented magnetic moment that brings out some of the strange implications of quantum mechanics.” Yep. That’s true. We’ll talk about that later.

Of course, you’ll probably want some ‘easier’ explanation. I am afraid I can’t give you that. All I can say is that, perhaps, you should think of our discussion on the fine-structure constant, which made it clear that the various radii of the electron, its velocity and its mass and/or energy are all related one to another and, hence, that they can only take on certain values. Indeed, of all the relations we discussed, there’s two you should always remember. The first relationship is the U = (e2/r) = α/r. So that links the energy (which we can express in equivalent mass units), the electron charge and its radius. The second thing you should remember is that the Bohr radius and the classical electron radius are also related through α: α re/r = α2. So you may want to think of the different values for J as being associated with different ‘orbitals’, so to speak. But that’s a very crude way of thinking about it, so I’d say: just accept the fact and see where it leads us. You’ll see, in a few moments from now, that the whole thing is not unlike the quantum-mechanical explanation of the blackbody radiation problem, which assumes that the permitted energy levels (or states) are equally spaced and h·f apart, with f the frequency of the light that’s being absorbed and/or emitted. So the atom takes up energies only h·f at a time. Here we’ve got something similar: the energy levels that we’ll associate with the discrete values of J – or J‘s components , I should say – will also be equally spaced. Let me show you how it works, as that will make things somewhat more clear.

If we have an object with a given total angular momentum J in classical mechanics, then any of its components x, y or z, could take on any value from +J to −J. That’s not the case here. The rule is that the ‘system’ – the atom, the nucleus, or anything really – will have a characteristic number, which is referred to as the ‘spin’ of the system and, somewhat confusingly, it’s denoted by j (as you can, it’s extremely important, indeed, to distinguish capital letters (like J) from small letters (like j) if you want to keep track of what we’re explaining here). Now, if we have that characteristic spin number j, then any component of J (think of the z-direction, for example) can take on only (one of) the following values:

Note that we will always have 2j + 1 values. For example, if j = 3/2, we’ll have 2·(3/2) + 1 = 4 permitted values, and in the extreme case where j is zero, we’ll still have 2·0 + 1 = 1 permitted value: zero itself. So that basically says we have no angular momentum. […] OK. That should be clear enough, but let’s pause here for a moment and analyze this—just to make sure we ‘get’ this indeed. What’s being written here? What are those numbers? Let’s do a quick dimensional analysis first. Because j, j − 1, j − 2, etcetera are pure numbers, it’s only the dimension of ħ that we need to look at. We know ħ: it’s the Planck constant h, which is expressed in joule·second, i.e. J·s = N·m·s, divided by 2π. That makes sense, because we get the same dimension for the angular momentum. Indeed, the L or J = r·m·v formula also gives us the dimension of physical action, i.e. N·m·s. Just check it: [r]·[m]·[v] = m·kg·m/s = m·(N·s2/m)·m/s = N·m·s. Done!

So we’ve got some kind of unit of action once more here, even if it’s not h but ħ = h/2π. That makes it a quantum of action expressed for a radian, so that’s a unit of length, rather than for a full cycle. Just so you know, ħ = h/2π is 1×10−34 J·s ≈ 6.6×10−16 eV·s, and we could chose to express the components of J in terms of h by multiplying the whole thing with 2π. That would boil down to saying that our unit length is not unity but the unit circle, which is 2π times unity. Huh? Just think about it: h is a fundamental unit linked to one full cycle of something, so it all makes sense. Before we move on, you may want to compare the value of h or ħ with the energy of a photon, which is 1.6 to 3.2 eV in the visible light spectrum, but you should note that energy does not have the time dimension, and a second is an eternity in quantum physics, so the comparison is a bit tricky. So… […] Well… Let’s just move on. What about those coefficients? What constraints are there?

Well… The constraint is that the difference between +j and −j must be some integer, so +j−(−j) = 2j must be an integer. That implies that the spin number j is always an integer or a half-integer, depending on whether j is even or odd. Let’s do a few examples:

- A lithium (Li-7) nucleus has spin j = 3/2 and, therefore, the permitted values for the angular momentum around any axis (the z-axis, for example) are: 3/2, 3/2−1=1/2, 3/2−2=−1/2, and −3/2—all times ħ of course! Note that the difference between +j and –j is 3, and each ‘step’ between those two levels is ħ, as we’d like it to be.

- The nucleus of the much rarer Lithium-6 isotope is one of the few stable nuclei that has spin j = 1, so the permitted values are 1, 0 and −1. Again, all needs to be multiplied with ħ to get the actual value for the J-component that we’re looking at. So each step is ‘one’ again, and the total difference (between +j and –j) is 2.]

- An electron is a spin-1/2 particle, and so there are only two permitted values: +ħ/2 and −ħ/2. So there is just one ‘step’ and it’s equal to the whole difference between +j and –j. In fact, this is the most common situation, because we’ll be talking elementary fermions most of the time.

- Photons are an example of spin-1 ‘particles’, and ‘particles’ with integer spin are referred to as bosons. In this regard, you may heard of superfluid Helium-4, which is caused by Bose-Einstein condensation near the zero temperature point, and demonstrates the integer spin number of Helium-4, so it resembles Lithium-6 in this regard.

The four ‘typical’ examples makes it clear that the actual situations that we’ll be analyzing will usually be quite simple: we’ll only have 2, 3 or 4 permitted values only. As mentioned, there is this fundamental dichotomy between fermions and bosons. Fermions have half-integer spin, and all elementary fermions, such as protons, neutrons, electrons, neutrinos and quarks are spin-1/2 particles. [Note that a proton and a neutron are, strictly speaking, not elementary, as their constituent parts are quarks.] Bosons have integer spin, and the bosons we know of are spin-one particles, (except for the newly discovered Higgs boson, which is an actual spin-zero particle). The photon is an example, but the helium nucleus (He-4) also has spin one, which – as mentioned above – gives rise to superfluidity when its cooled near the absolute zero point.

In any case, to make a long story short, in practice, we’ll be dealing almost exclusively with spin-1, spin-1/2 particles and, occasionally, with spin-3/2 particles. In addition, to analyze simple stuff, we’ll often pretend particles do not have any spin, so our ‘theoretical’ particles will often be spin zero. That’s just to simplify stuff.

We now need to learn how to do a bit of math with all of this. Before we do so, let me make some additional remarks on these permitted values. Regardless of whether or not J is ‘wobbling’ or moving or not – let me be clear: J is not moving in the analysis above, but we’ll discuss the phenomenon of precession in the next post, and that will involve a J like that J circling around the Jz axis, so I am just preparing the terrain here – J‘s magnitude will always be some constant, which we denoted by |J| = J.

Now there’s something really interesting here, which again distinguishes classical mechanics from quantum mechanics. As mentioned, in classical mechanics, any of J‘s components Jx, Jy or Jz, could take on any value from +J to −J and, therefore, the maximum value of any component of J – say Jz – would be equal to J. To be precise, J would be the value of the component of J in the direction of J itself. So, in classical mechanics, we’d write: |J| = +√(J·J) = +√J2 = J, and it would be the maximum value of any component of J. But so we said that, if the spin number of J is j, then the maximum value of any component of J was equal to j·ħ. So, naturally, one would think that J = |J| = +√(J·J) = +√J2 = j·ħ.

However, that’s not the case in quantum mechanics: the maximum value of any component of J is not J = j·ħ but the square root of j·(j+1)·ħ.

Huh? Yes. Let me spell it out: |J| = +√(J·J) = +√J2 ≠ jħ. Indeed, quantum math has many particularities, and this is one of them. The magnitude of J is not equal to the largest possible value of any component of J:

J‘s magnitude is not jħ but √(j(j+1)ħ).

As for the proof of this, let me simplify my life and just copy Feynman here:

The formula can be easily generalized for j ≠ 3/2. Also note that we used a fact that we didn’t mention as yet: all possible values of the z-component (or of whatever component) of J are equally likely.

Now, the result is fascinating, but the implications are even better. Let me paraphrase Feynman as he relates them:

- From what we have so far, we can get another interesting and somewhat surprising conclusion. In certain classical calculations the quantity that appears in the final result is the square of the magnitude of the angular momentum J—in other words, J⋅J = J2. It turns out that it is often possible to guess at the correct quantum-mechanical formula by using the classical calculation and the following simple rule: Replace J2 = J⋅J by j(j+1)ħ. This rule is commonly used, and usually gives the correct result.

- The second implication is the one we announced already: although we would think classically that the largest possible value of the any component of J is just the magnitude of J, quantum-mechanically the maximum of any component of J is always less than that, because jħ is always less than √(j(j+1)ħ). For example, for j = 3/2 = 1.5, we have j(j+1) = (3/2)·(5/2) = 15/4 = 3.75. Now, the square root of this value is √3.75 ≈ 1.9365, so the magnitude of J is about 30% larger than the maximum value of any of J‘s components. That’s a pretty spectacular difference, obviously!

The second point is quite deep: it implies that the angular momentum is ‘never completely along any direction’. Why? Well… Think of it: “any of J‘s components” also includes the component in the direction of J itself! But if the maximum value of that component is 30% less than the magnitude of J, what does that mean really? All we can say is that it implies that the concept of the direction of the magnitude itself is actually quite fuzzy in quantum mechanics! Of course, that’s got to do with the Uncertainty Principle, and so we’ll come back to this later.

In fact, if you look at the math, you may think: what’s that business with those average or expected values? A magnitude is a magnitude, isn’t it? It’s supposed to be calculated from the actual values of Jx, Jy and Jz, not from some average that’s based on the (equal) likelihoods of the permitted values. You’re right. Feynman’s derivation here is quantum-mechanical from the start and, therefore, we get a quantum-mechanical result indeed: the magnitude of J is calculated as the magnitude of a quantum-mechanical variable in the derivation above, not as the magnitude of a classical variable.

[…] OK. On to the next.

The magnetic energy of atoms

Before we start talking about this topic, we should, perhaps, relate the angular momentum to the magnetic moment once again. We can do that using the μ = (q/2m)·J and/or μ = (q/m)·J formula (so that’s the simple formulas for the orbital and spin angular momentum respectively) or, else, by using the more general μ = – g·(q/2m)·J formula.

Let’s use the simpler μ = (qe/2m)·J formula, which is the one for the orbital angular momentum. What’s qe/2m? It should be equal to 1.6×10−19 C divided by 2·9.1×10−31 kg, so that’s about 0.0879×1012 C/kg, or 0.0879×1012 (C·m)/(N·s2). Now we multiply by ħ/2 ≈ 0.527×10−34 J·s. We get something like 0.0463×10−22 m2·C/s or J/T. These numbers are ridiculously small, so they’re usually measured in terms of a so-called natural unit: the Bohr magneton, which I’ll explain in a moment but so here we’re interested in its value only, which is μB = 9.274×10−24 J/T. Hence, μ/μB = 0.5 = 1/2. What a nice number!

Hmm… This cannot be a coincidence… […] You’re right. It isn’t. To get the full picture, we need to include the spin angular momentum, so we also need to see what the μ = (q/m)·J will yield. That’s easy, of course, as it’s twice the value of (q/2m)·J, so μ/μB = 1, and so the total is equal to 3/2. So the magnetic moment of an electron has the same value (when expressed in terms of the Bohr magneton) as the spin (when expressed in terms of ħ). Now that’s just sweet!

Yes, it is. All our definitions and formulas were formulated so as to make it sweet. Having said that, we do have a tiny little problem. If we use the general μ = −g·(q/2m)·J to write the result we found for the spin of the electron only (so we’re not looking at the orbital momentum here), then we’d write: μ = 2·(q/2m)·J = (q/m)·J and, hence, the g-factor here is −2. Yes. We know that. You told me so already. What’s the issue? Well… The problem is: experiments reveal the actual value of g is not exactly −2: it’s −2.00231930436182(52) instead, with the last two digits (in brackets) the uncertainty in the current measurements. Just check it for yourself on the NIST website. 🙂 [Please do check it: it brings some realness to this discussion.]

Hmm…. The accuracy of the measurement suggests we should take it seriously, even if we’re talking a difference of 0.1% only. We should. It can be explained, of course: it’s something quantum-mechanical. However, we’ll talk about this later. As for now, just try to understand the basics here. It’s complicated enough already, and so we’ll stay away from the nitty-gritty as long as we can.

Let’s now get back to the magnetic energy of our atoms. From our discussion on the torque on a magnetic dipole in an external magnetic field, we know that our magnetic atoms will have some extra magnetic energy when placed in an external field. So now we have an external magnetic field B, and we derived the formula for the energy is

Umag = −μ·B·cosθ = −μ·B

I won’t explain the whole thing once again, but it might help to visualize the situation, which we do below. The loop here is not circular but square, and it’s a current-carrying wire instead of an electron in orbit, but I hope you get the point.

We need to chose some coordinate system to calculate stuff and so we’ll just choose our z-axis along the direction of the external magnetic field B so as to simplify those calculations. If we do that, we can just take the z-component of μ and then combine the interim result with our general μ = – g·(q/2m)·J formula, so we write:

Umag = −μz·B = g·(q/2m)·Jz·B

Now, we know that the maximum value of Jz is equal to j·ħ, and so the maximum value of Umag will be equal g(q/2m)jħB. Let’s now simplify this expression by choosing some natural unit, and that’s the unit we introduced already above: the Bohr magneton. It’s equal to (qeħ)/(2me) and its value is μB ≈ 9.274×10−24 J/T. So we get the result we wanted, and that is:

Let me make a few remarks here. First on that magneton: you should note there’s also something which is known as the nuclear magneton which, you guessed it, is calculated using the proton charge and the proton mass: μN = (qpħ)/(2mp) ≈ 5.05×10−27 J/T. My second remark is a question: what does that formula mean, really? Well… Let me quote Feynman on that. The formula basically says the following:

“The energy of an atomic system is changed when it is put in a magnetic field by an amount that is proportional to the field, and proportional to Jz. We say that the energy of an atomic system is ‘split’ into 2j + 1 ‘levels’ by a magnetic field. For instance, an atom whose energy is U0 outside a magnetic field and whose j is 3/2, will have four possible energies when placed in a field. We can show these energies by an energy-level diagram like that drawn below. Any particular atom can have only one of the four possible energies in any given field B. That is what quantum mechanics says about the behavior of an atomic system in a magnetic field.”

Of course, the simplest ‘atomic’ system is a single electron, which has spin 1/2 only (like most fermions really: the example in the diagram above, with spin 3/2, would be that Li-7 system or something similar). If the spin is 1/2, then there are only two energy levels, with Jz = ±ħ/2 and, as we mentioned already, the g-factor for an electron is −2 (again, the use of minus signs (or not) is quite confusing: I am sorry for that), and so our formula above becomes very simple:

Umag = ± μB·B

The graph above becomes the graph below, and we can now speak more loosely and say that the electron either has its spin ‘up’ (so that’s along the field), or ‘down’ (so that’s opposite the field).

By now, you’re probably tired of the math and you’ll wonder: how can we prove all of this permitted value business? Well… That question leads me to the last topic of my post: the Stern-Gerlach experiment.

The Stern-Gerlach experiment

Here again, I can just copy straight of out of Feynman, and so I hope you’ll forgive me if I just do that, as I don’t think there’s any advantage to me trying to summarize what he writes on it:

“The fact that the angular momentum is quantized is such a surprising thing that we will talk a little bit about it historically. It was a shock from the moment it was discovered (although it was expected theoretically). It was first observed in an experiment done in 1922 by Stern and Gerlach. If you wish, you can consider the experiment of Stern-Gerlach as a direct justification for a belief in the quantization of angular momentum. Stern and Gerlach devised an experiment for measuring the magnetic moment of individual silver atoms. They produced a beam of silver atoms by evaporating silver in a hot oven and letting some of them come out through a series of small holes. This beam was directed between the pole tips of a special magnet, as shown in the illustration below. Their idea was the following. If the silver atom has a magnetic moment μ, then in a magnetic field B it has an energy −μzB, where z is the direction of the magnetic field. In the classical theory, μz would be equal to the magnetic moment times the cosine of the angle between the moment and the magnetic field, so the extra energy in the field would be

ΔU = −μ·B·cosθ

Of course, as the atoms come out of the oven, their magnetic moments would point in every possible direction, so there would be all values of θ. Now if the magnetic field varies very rapidly with z—if there is a strong field gradient—then the magnetic energy will also vary with position, and there will be a force on the magnetic moments whose direction will depend on whether cosine θ is positive or negative. The atoms will be pulled up or down by a force proportional to the derivative of the magnetic energy; from the principle of virtual work,

Stern and Gerlach made their magnet with a very sharp edge on one of the pole tips in order to produce a very rapid variation of the magnetic field. The beam of silver atoms was directed right along this sharp edge, so that the atoms would feel a vertical force in the inhomogeneous field. A silver atom with its magnetic moment directed horizontally would have no force on it and would go straight past the magnet. An atom whose magnetic moment was exactly vertical would have a force pulling it up toward the sharp edge of the magnet. An atom whose magnetic moment was pointed downward would feel a downward push. Thus, as they left the magnet, the atoms would be spread out according to their vertical components of magnetic moment. In the classical theory all angles are possible, so that when the silver atoms are collected by deposition on a glass plate, one should expect a smear of silver along a vertical line. The height of the line would be proportional to the magnitude of the magnetic moment. The abject failure of classical ideas was completely revealed when Stern and Gerlach saw what actually happened. They found on the glass plate two distinct spots. The silver atoms had formed two beams.

That a beam of atoms whose spins would apparently be randomly oriented gets split up into two separate beams is most miraculous. How does the magnetic moment know that it is only allowed to take on certain components in the direction of the magnetic field? Well, that was really the beginning of the discovery of the quantization of angular momentum, and instead of trying to give you a theoretical explanation, we will just say that you are stuck with the result of this experiment just as the physicists of that day had to accept the result when the experiment was done. It is an experimental fact that the energy of an atom in a magnetic field takes on a series of individual values. For each of these values the energy is proportional to the field strength. So in a region where the field varies, the principle of virtual work tells us that the possible magnetic force on the atoms will have a set of separate values; the force is different for each state, so the beam of atoms is split into a small number of separate beams. From a measurement of the deflection of the beams, one can find the strength of the magnetic moment.”

I should note one point which Feynman hardly addresses in the analysis above: why do we need a non-homogeneous field? Well… Think of it. The individual silver atoms are not like electrons in some electric field. They are tiny little magnets, and magnets do not behave like electrons. Remember we said there’s no such thing as a magnetic charge? So that applies here. If the silver atoms are tiny magnets, with a magnetic dipole moment, then the only thing they will do is turn, so as to minimize their energy U = −μBcosθ.

That energy is minimized when μ and B are at right angles of each other, so as to make the cosθ factor zero, which happens when θ = π/2. Hence, in a homogeneous magnetic field, we will have a torque on the loop of current – think of our electron(s) in orbit here – but no net force pulling it in this or that direction as a whole. So the atoms would just rotate but not move in our classical analysis here.

To make the atoms themselves move towards or away one of the poles (with or without a sharp tip), the magnetic field must be non-homogeneous, so as to ensure that the force that’s pulling on one side of the loop of current is slightly different from the force that’s pulling (in the opposite direction) on the other side of the loop of current. So that’s why the field has to be non-homogeneous (or inhomogeneous as Feynman calls it), and so that’s why one pole needs to have a sharply pointed tip.

As for the force formula, it’s crucial to remember that energy (or work) is force times distance. To be precise, it’s the ∫F∙ds integral. This integral will have a minus sign in front when we’re doing work against the force, so that’s when we’re increasing the potential energy of an object. Conversely, we’ll just take the positive value when we’re converting potential energy into kinetic energy. So that explains the F = −∂U/∂z formula above. In fact, in the analysis above, Feynman assumes the magnetic moment doesn’t turn at all. That’s pretty obvious from the Fz = −∂U/∂z = −μ∙cosθ∙∂B/∂z formula, in which μ is clearly being treated as a constant. So the Fz in this formula is a net force in the z-direction, and it’s crucially dependent on the variation of the magnetic field in the z-direction. If the field would not be varying, ∂B/∂z would be zero and, therefore, we would not have any net force in the z-direction. As mentioned above, we would only have a torque.

Well… This sort of covers all of what we wanted to cover today. 🙂 I hope you enjoyed it.

Some content on this page was disabled on June 16, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here:

https://wordpress.com/support/copyright-and-the-dmca/

Some content on this page was disabled on June 16, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here:https://wordpress.com/support/copyright-and-the-dmca/

Some content on this page was disabled on June 16, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here: