I’ve been looking at chapter 4 of Feynman’s Lectures on Quantum Mechanics (the chapter on identical particles) for at least a dozen times now—probably more. This and the following chapters spell out the mathematical framework and foundations of mainstream quantum mechanics: the grand distinction between fermions and bosons, symmetric and asymmetric wavefunctions, Bose-Einstein versus Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics, and whatever else comes out of that—including the weird idea that (force) fields should also come in lumps (think of quantum field theory here). These ‘field lumps’ are then thought of as ‘virtual’ particles that, somehow, ‘mediate’ the force.

The idea that (kinetic and/or potential) energy and (linear and/or angular) momentum are being continually transferred – somehow, and all over space – by these ‘messenger’ particles sounds like medieval philosophy to me. However, to be fair, Feynman does actually not present these more advanced medieval ideas in his Lectures on Quantum Physics. I have always found that somewhat strange: he was about to receive a Nobel Prize for his path integral formulation of quantum mechanics and other contributions to what has now become the mainstream interpretation of quantum mechanics, so why wouldn’t he talk about it to his students, for which he wrote these lectures? In contrast, he does include a preview of Gell-Mann’s quark theory, although he does say – in a footnote – that “the material of this section is longer and harder than is appropriate at this point” and he, therefore, suggests to skip it and move to the next chapter.

[As for the path integral formulation of QM, I would think the mere fact that we have three alternative formulations of QM (matrix, wave-mechanical and path integral) would be sufficient there’s something wrong with these theories: reality is one, so we should have one unique (mathematical) description of it).]

Any case. I am probably doing too much Hineininterpretierung here. Let us return to the basic stuff that Feynman wanted his students to accept as a truthful description of reality: two kinds of statistics. Two different ways of interaction. Two kinds of particles. That’s what post-WW II gurus such as Feynman – all very much inspired by the ‘Club of Copenhagen’—aka known as the ‘Solvay Conference Club‘ – want us to believe: interactions with ‘Bose particles’ – this is the term Feynman uses in this text of 1963 – involve adding amplitudes with a + (plus) sign. In contrast, interactions between ‘Fermi particles’ involve a minus (−) sign when ‘adding’ the amplitudes.

The confusion starts early on: Feynman makes it clear he actually talks about the amplitude for an event to happen or not. Two possibilities are there: two ‘identical’ particles either get ‘swapped’ after the collision or, else, they don’t. However, in the next sections of this chapter – where he ‘proves’ or ‘explains’ the principle of Bose condensation for bosons and then the Pauli exclusion principle for fermions – it is very clear the amplitudes are actually associated with the particles themselves.

So his argument starts rather messily—conceptually, that is. Feynman also conveniently skips the most basic ontological or epistemological question here: how would a particle ‘know‘ how to choose between this or that kind of statistics? In other words, how does it know it should pick the plus or the minus sign when combining its amplitude with the amplitude of the other particle? It makes one think of Feynman’s story of the Martian in his Lecture on symmetries in Nature: what handshake are we going to do here? Left or right? And who sticks out his hand first? The Martian or the Earthian? A diplomat would ask: who has precedence when the two particles meet?

The question also relates to the nature of the wavefunction: if it doesn’t describe anything real, then where is it? In our mind only? But if it’s in our mind only, how comes we get real-life probabilities out of them, and real-life energy levels, or real-life momenta, etcetera? The core question (physical, epistemological, philosophical, esoterical or whatever you’d want to label it) is this: what’s the connection between these concepts and whatever it is that we are trying to describe? The only answer mainstream physicists can provide here is blabber. That’s why the mainstream interpretation of physics may be acceptable to physicists, but not to the general public. That’s why the debate continues to rage: no one believes the Standard Model. Full stop. The intuition of the masses here is very basic and, therefore, probably correct: if you cannot explain something in clear and unambiguous terms, then you probably do not understand it.

Hence, I suspect mainstream academic physicists probably do not understand whatever it is they are talking about. Feynman, by the way, admitted as much when writing – in the very first lines of the introduction to his Lectures on Quantum Mechanics – that “even the experts do not understand it the way they would like to.”

I am actually appalled by all of this. Worse, I am close to even stop talking or writing about it. I only kept going because a handful of readers send me a message of sympathy from time to time. I then feel I am actually not alone in what often feels like a lonely search in what a friend of mine refers to as ‘a basic version of truth.’ I realize I am getting a bit emotional here – or should I say: upset? – so let us get back to Feynman’s argument again.

Feynman starts by introducing the idea of a ‘particle’—a concept he does not define – not at all, really – but, as the story unfolds, we understand this concept somehow combines the idea of a boson and a fermion. He doesn’t motivate why he feels like he should lump photons and electrons together in some more general category, which he labels as ‘particles’. Personally, I really do not see the need to do that: I am fine with thinking of a photon as an electromagnetic oscillation (a traveling field, that is), and of electrons, protons, neutrons and whatever composite particle out there that is some combination of the latter as matter-particles. Matter-particles carry charge: electric charge and – who knows – perhaps some strong charge too. Photons don’t. So they’re different. Full stop. Why do we want to label everything out there as a ‘particle’?

Indeed, when everything is said and done, there is no definition of fermions and bosons beyond this magical spin-1/2 and spin-1 property. That property is something we cannot measure: we can only measure the magnetic moment of a particle: any assumption on their angular momentum assumes you know the mass (or energy) distribution of the particle. To put it more plainly: do you think of a particle as a sphere, a disk, or what? Mainstream physicists will tell you that you shouldn’t think that way: particles are just pointlike. They have no dimension whatsoever – in their mathematical models, that is – because all what experimentalists is measuring scattering or charge radii, and these show the assumption of an electron or a proton being pointlike is plain nonsensical.

Needless to say, besides the perfect scattering angle, Feynman also assumes his ‘particles’ have no spatial dimension whatsoever: he’s just thinking in terms of mathematical lines and points—in terms of mathematical limits, not in terms of the physicality of the situation.

Hence, Feynman just buries us under a bunch of tautologies here: weird words are used interchangeably without explaining what they actually mean. In everyday language and conversation, we’d think of that as ‘babble’. The only difference between physicists and us commoners is that physicists babble using mathematical language.

[…]

I am digressing again. Let us get back to Feynman’s argument. So he tells us we should just accept this theoretical ‘particle’, which he doesn’t define: he just thinks about two of these discrete ‘things’ going into some ‘exchange’ or ‘interaction’ and then coming out of it and going into one of the two detectors. The question he seeks to answer is this: can we still distinguish what is what after the ‘interaction’?

The level of abstraction here is mind-boggling. Sadly, it is actually worse than that: it is also completely random. Indeed, the only property of this mystical ‘particle’ in this equally mystical thought experiment of Mr. Feynman is that it scatters elastically with some other particle. However, that ‘other’ particle is ‘of the same kind’—so it also has no other property than that it scatters equally elastically from the first particle. Hence, I would think the question of whether the two particles are identical or not is philosophically empty.

To be rude, I actually wonder what Mr. Feynman is actually talking about here. Every other line in the argument triggers another question. One should also note, for example, that this elastic scattering happens in a perfect angle: the whole argument of adding or subtracting amplitudes effectively depends on the idea of a perfectly measurable angle here. So where is the Uncertainty Principle here, Mr. Feynman? It all makes me think that Mr. Feynman’s seminal lecture may well be the perfect example of what Prof. Dr. John P. Ralston wrote about his own profession:

“Quantum mechanics is the only subject in physics where teachers traditionally present haywire axioms they don’t really believe, and regularly violate in research.” (1)

Let us continue exposing Mr. Feynman’s argument. After this introduction of this ‘particle’ and the set-up with the detectors and other preconditions, we then get two or three paragraphs of weird abstract reasoning. Please don’t get me wrong: I am not saying the reasoning is difficult (it is not, actually): it is just weird and abstract because it uses complex number logic. Hence, Feynman implicitly requests the reader to believe that complex numbers adequately describes whatever it is that he is thinking of (I hope – but I am not so sure – he was trying to describe reality). In fact, this is the one point I’d agree with him: I do believe Euler’s function adequately describes the reality of both photons and electrons (see our photon and electron models), but then I also think +i and −i are two very different things. Feynman doesn’t, clearly.

It is, in fact, very hard to challenge Feynman’s weird abstract reasoning here because it all appears to be mathematically consistent—and it is, up to the point of the tricky physical meaning of the imaginary unit: Feynman conveniently forgets the imaginary unit represents a rotation of 180 degrees and that we, therefore, need to distinguish between these two directions so as to include the idea of spin. However, that is my interpretation of the wavefunction, of course, and I cannot use it against Mr. Feynman’s interpretation because his and mine are equally subjective. One can, therefore, only credibly challenge Mr. Feynman’s argument by pointing out what I am trying to point out here: the basic concepts don’t make any sense—none at all!

Indeed, if I were a student of Mr. Feynman, I would have asked him questions like this:

“Mr. Feynman, I understand your thought experiment applies to electrons as well as to photons. In fact, the argument is all about the difference between these two very different ‘types’ of ‘particles’. Can you please tell us how you’d imagine two photons scattering off each other elastically? Photons just pile on top of each other, don’t they? In fact, that’s what you prove next. So they don’t scatter off each other, do they? Your thought experiment, therefore, seems to apply to fermions only. Hence, it would seem we should not use it to derive properties for bosons, isn’t it?”

“Mr. Feynman, how should an electron (a fermion – so you say we should ‘add’ amplitudes using a minus sign) ‘think’ about what sign to use for interaction when a photon is going to hit it? A photon is a boson – so its sign for exchange is positive – so should we have an ‘exchange’ or ‘interaction’ with the plus or the minus sign then? More generally, who takes the ‘decisions’ here? Do we expect God – or Maxwell’s demon – to be involved in every single quantum-mechanical event?”

Of course, Mr. Feynman might have had trouble answering the first question, but he’d probably would not hesitate to produce some kind of rubbish answer to the second: “Mr. Van Belle, we are thinking of identical particles here. Particles of the same kind, if you understand what I mean.”

Of course, I obviously don’t understand what he means but so I can’t tell him that. So I’d just ask the next logical question to try to corner him:

“Of course, Mr. Feynman. Identical particles. Yes. So, when thinking of fermion-on-fermion scattering, what mechanism do you have in mind? At the very least, we should be mindful of the difference between Compton versus Thomson scattering, shouldn’t we? How does your ‘elastic’ scattering relate to these two very different types of scattering? What is your theoretical interaction mechanism here?”

I can actually think of some more questions, but I’ll leave it at this. Well… No… Let me add another one:

“Mr. Feynman, this theory of interaction between ‘identical’ or ‘like’ particles (fermions and bosons) looks great but, in reality, we will also have non-identical particles interacting with each other—or, more generally speaking, particles that are not ‘of the same kind’. To be very specific, reality sees many electrons and many photons interacting with each other—not just once, at the occasion of some elastic collision, but all of the time, really. So could we, perhaps, generalize this to some kind of ‘three- or n-particle problem’?”

This sounds like a very weird question, which even Mr. Feynman might not immediately understand. So, if he didn’t shut me up already, he may have asked me to elaborate: “What do you mean, Mr. Van Belle? What kind of three- or n-particle problem are you talking about?” I guess I’d say something like this:

“Well… Already in classical physics, we do not have an analytical solution for the ‘three-body problem’, but at least we have the equations. So we have the underlying mechanism. What are the equations here? I don’t see any. Let us suppose we have three particles colliding or scattering or interacting or whatever it is we are trying to think of. How does any of the three particles know what the other two particles are going to be: a boson or a fermion? And what sign should they then use for the interaction? In fact, I understand you are talking amplitudes of events here. If three particles collide, how many events do you count: one, two, three, or six?”

One, two, three or six? Yes. Do we think of the interaction between three particles as one event, or do we split it up as a triangular thing? Or is it one particle interacting, somehow, with the two other, in which case we’re having two events, taking into account this weird plus or minus sign rule for interaction.

Crazy? Yes. Of course. But the questions are logical, aren’t they? I can think of some more. Here is one that, in my not-so-humble view, shows how empty these discussions on the theoretical properties of theoretical bosons and theoretical fermions actually are:

“Mr. Feynman, you say a photon is a boson—a spin-one particle, so its spin state is either 1, 0 or −1. How comes photons – the only boson that we actually know to exist from real-life experiments – do not have a spin-zero state? Their spin is always up or down. It’s never zero. So why are we actually even talking about spin-one particles, if the only boson we know – the photon – does not behave like it should behave according to your boson-fermion theory?” (2)

Am I joking? I am not. I like to think I am just asking very reasonable questions here—even if all of this may sound like a bit of a rant. In fact, it probably is, but so that’s why I am writing this up in a blog rather than in a paper. Let’s continue.

The subsequent chapters are about the magical spin-1/2 and spin-1 properties of fermions and bosons respectively. I call them magical, because – as mentioned above – all we can measure is the magnetic moment. Any assumption that the angular momentum of a particle – a ‘boson’ or a ‘fermion’, whatever it is – is ±1 or ±1/2, assumes we have knowledge of some form factor, which is determined by the shape of that particle and which tells us how the mass (or the energy) of a particle is distributed in space.

Again, that may sound sacrilegious: according to mainstream physicists, particles are supposed to be pointlike—which they interpret as having no spatial dimension whatsoever. However, as I mentioned above, that sounds like a very obvious oxymoron to me.

Of course, I know I would never have gotten my degree. When I did the online MIT course, the assistants of Prof. Dr. Zwieback also told me I asked too many questions: I should just “shut up and calculate.” You may think I’m joking again but, no: that’s the feedback I got. Needless to say, I went through the course and did all of the stupid exercises, but I didn’t bother doing the exams. I don’t mind calculating. I do a lot of calculations as a finance consultant. However, I do mind mindless calculations. Things need to make sense to me. So, yes, I will always be an ‘amateur physicist’ and a ‘blogger’—read: someone whom you shouldn’t take very seriously. I just hope my jokes are better than Feynman’s.

I’ve actually been thinking that getting a proper advanced degree in physics might impede understanding, so it’s good I don’t have one. I feel these mainstream courses do try to ‘brainwash’ you. They do not encourage you to challenge received wisdom. On the contrary, it all very much resembles rote learning: memorization based on repetition. Indeed, more modern textbooks – I looked at the one of my son, for example – immediately dive into the hocus-pocus—totally shamelessly. They literally start by saying you should not try to understand and that you just get through the math and accept the quantum-mechanical dogmas and axioms! Despite the appalling logic in the introductory chapters, Mr. Feynman, in contrast, at least has the decency to try to come up with some classical arguments here and there (although he also constantly adds that the student should just accept the hocus-pocus approach and the quantum-mechanical dogmas and not think too much about what it might or might not represent).

My son got high marks on his quantum mechanics exam: a 19/20, to be precise, and so I am really proud of him—and I also feel our short discussions on this or that may have helped him to get through it. Fortunately, he was doing it as part of getting a civil engineering degree (Bachelor’s level), and he was (also) relieved he would never have to study the subject-matter again. Indeed, we had a few discussions and, while he (also) thinks I am a bit of a crackpot theorist, he does agree “the math must describe something real” and that “therefore, something doesn’t feel right in all of that math.” I told him that I’ve got this funny feeling that, 10 or 20 years from now, 75% (more?) of post-WW II research in quantum physics – most of the theoretical research, at least (3) – may be dismissed as some kind of collective psychosis or, worse, as ‘a bright shining lie’ (title of a book I warmly recommend – albeit on an entirely different topic). Frankly, I think many academics completely forgot Boltzmann’s motto for the physicist:

“Bring forward what is true. Write it so that it is clear. Defend it to your last breath.”

[…]

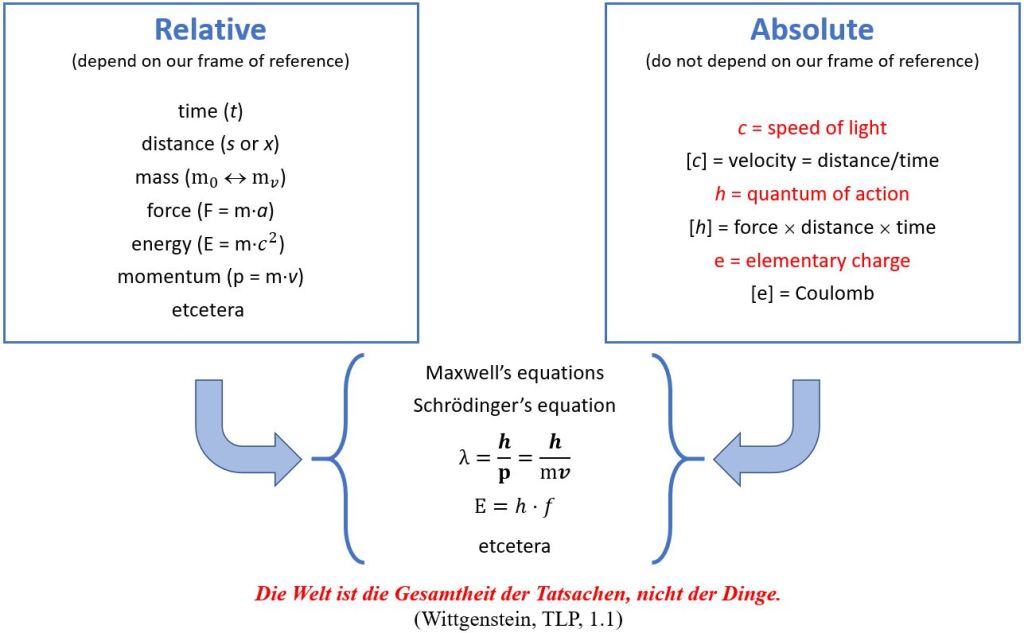

OK, you’ll say: get real! So what is the difference between bosons and fermions, then? I told you already: I think it’s a useless distinction. Worse, I think it’s not only useless but it’s also untruthful. It has, therefore, hampered rather than promoted creative thinking. I distinguish matter-particles – electrons, protons, neutrons – from photons (and neutrinos). Matter-particles carry charge. Photons (and neutrinos) do not. (4) Needless to say, I obviously don’t believe in ‘messenger particles’ and/or ‘Higgs’ or other ‘mechanisms’ (such as the ‘weak force’ mechanism). That sounds too much like believing in God or some other non-scientific concept. [I don’t mind you believing in God or some other non-scientific concept – I actually do myself – but we should not confuse it with doing physics.]

And as for the question on what would be my theory of interaction? It’s just the classical theory: charges attract or repel, and one can add electromagnetic fields—all in respect of the Planck-Einstein law, of course. Charges have some dimension (and some mass), so they can’t take up the same space. And electrons, protons and neutrons have some structure, and physicists should focus on modeling those structures, so as to explain the so-called intrinsic properties of these matter-particles. As for photons, I think of them as an oscillating electromagnetic field (respecting the Planck-Einstein law, of course), and so we can simply add them. What causes them to lump together? Not sure: the Planck-Einstein law (being in some joint excited state, in other words) or gravity, perhaps. In any case: I am confident it is something real—i.e. not Feynman’s weird addition or subtraction rules for amplitudes.

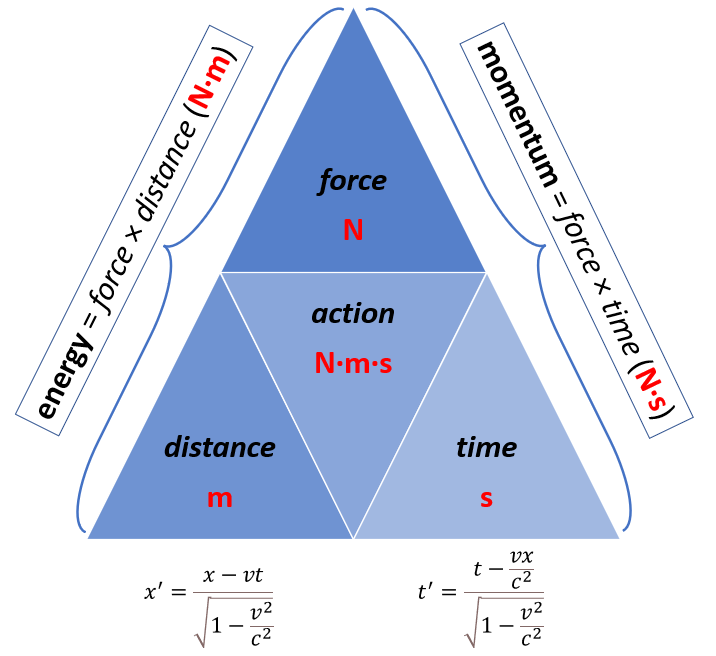

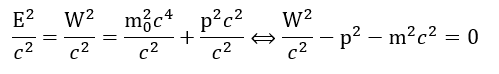

However, this is not the place to re-summarize all of my papers. I’d just sum them up by saying this: not many physicists seem to understand Planck’s constant or, what amounts to the same, the concept of an elementary cycle. And their unwillingness to even think about the possible structure of photons, electrons and protons is… Well… I’d call it criminal.

[…]

I will now conclude my rant with another down-to-earth question: would I recommend reading Feynman’s Lectures? Or recommend youngsters to take up physics as a study subject?

My answer in regard to the first question is ambiguous: yes, and no. When you’d push me on this, I’d say: more yes than no. I do believe Feynman’s Lectures are much better than the modern-day textbook that was imposed on my son during his engineering studies and so, yes, I do recommend the older textbooks. But please be critical as you go through them: do ask yourself the same kind of questions that I’ve been asking myself while building up this blog: think for yourself. Don’t go by ‘authority’. Why not? Because the possibility that a lot of what labels itself as science may be nonsensical. As nonsensical as… Well… All what goes on in national and international politics for the moment, I guess. 🙂

In regard to the second question – should youngsters be encouraged to study physics? – I’d say what my father told me when I was hesitating to pick a subject for study: “Do what earns respect and feeds your family. You can do philosophy and other theoretical things on the side.”

With the benefit of hindsight, I can say he was right. I’ve done the stuff I wanted to do—on the side, indeed. So I told my son to go for engineering – rather than pure math or pure physics. 🙂 And he’s doing great, fortunately !

Jean Louis Van Belle

Notes:

(1) Dr. Ralston’s How To Understand Quantum Mechanics is fun for the first 10 pages or so, but I would not recommend it. We exchanged some messages, but then concluded that our respective interpretations of quantum mechanics are very different (I feel he replaces hocus-pocus by other hocus-pocus) and, hence, that we should not “waste any electrons” (his expression) on trying to convince each other.

(2) It is really one of the most ridiculous things ever. Feynman spends several chapters on explaining spin-one particles to, then, in some obscure footnote, suddenly write this: “The photon is a spin-one particle which has, however, no “zero” state.” From all of his jokes, I think this is his worst. It just shows how ‘rotten’ or ‘random’ the whole conceptual framework of mainstream QM really is. There is, in fact, another glaring inconsistency in Feynman’s Lectures: in the first three chapters of Volume III, he talks about adding wavefunctions and the basic rules of quantum mechanics, and it all happens with a plus sign. In this chapter, he suddenly says the amplitudes of fermions combine with a minus sign. If you happen to know a physicist who can babble his way of out this inconsistency, please let me know.

(3) There are exceptions, of course. I mentioned very exciting research in various posts, but most of it is non-mainstream. The group around Herman Batalaan at the University of Nebraska and various ‘electron modellers’ are just one of the many examples. I contacted a number of these ‘particle modellers’. They’re all happy I show interest, but puzzled themselves as to why their research doesn’t get all that much attention. If it’s a ‘historical accident’ in mankind’s progress towards truth, then it’s a sad one.

(4) We believe a neutron is neutral because it has both positive and negative charge in it (see our paper on protons and neutrons). as for neutrinos, we have no idea what they are, but our wild guess is that they may be the ‘photons’ of the strong force: if a photon is nothing but an oscillating electromagnetic field traveling in space, then a neutrino might be an oscillating strong field traveling in space, right? To me, it sounds like a reasonable hypothesis, but who am I, right? 🙂 If I’d have to define myself, it would be as one of Feynman’s ideal students: someone who thinks for himself. In fact, perhaps I would have been able to entertain him as much as he entertained me— and so, who knows, I like to think he might actually have given me some kind of degree for joking too ! 🙂

(5) There is no (5) in the text of my blog post, but I just thought I would add one extra note here. 🙂 Herman Batelaan and some other physicists wrote a Letter to the Physical Review Journal back in 1997. I like Batelaan’s research group because – unlike what you might think – most of Feynman’s thought experiments have actually never been done. So Batelaan – and some others – actually did the double-slit experiment with electrons, and they are doing very interesting follow-on research on it.

However, let me come to the point I want to mention here. When I read these lines in that very serious Letter, I didn’t know whether to laugh or to cry:

“Bohr’s assertion (on the impossibility of doing a Stern-Gerlach experiment on electrons or charged particles in general) is thus based on taking the classical limit for ħ going to 0. For this limit not only the blurring, but also the Stern-Gerlach splitting vanishes. However, Dehmelt argues that ħ is a nonzero constant of nature.”

I mean… What do you make of this? Of course, ħ is a nonzero constant, right? If it was zero, the Planck-Einstein relation wouldn’t make any sense, would it? What world were Bohr, Heisenberg, Pauli and others living in? A different one than ours, I guess. But that’s OK. What is not OK, is that these guys were ignoring some very basic physical laws and just dreamt up – I am paraphrasing Ralston here – “haywire axioms they did not really believe in, and regularly violated themselves.” And they didn’t know how to physically interpret the Planck-Einstein relation and/or the mass-energy equivalence relation. Sabine Hossenfelder would say they were completely lost in math. 🙂

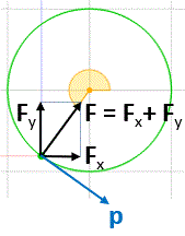

What are the implications for the assumed centripetal force keeping the elementary charge in motion? The centripetal acceleration is equal to ac = vt2/a = a·ω2. It is probably useful to remind ourselves how we get this result so as to make sure our calculations are relativistically correct. The position vector r (which describes the position of the zbw charge) has a horizontal and a vertical component: x = a·cos(ωt) and y = a·sin(ωt). We can now calculate the two components of the (tangential) velocity vector v = dr/dt as vx = –a·ω·sin(ωt) and vy y = –a· ω·cos(ωt) and, in the next step, the components of the (centripetal) acceleration vector ac: ax = –a·ω2·cos(ωt) and ay = –a·ω2·sin(ωt). The magnitude of this vector is then calculated as follows:

What are the implications for the assumed centripetal force keeping the elementary charge in motion? The centripetal acceleration is equal to ac = vt2/a = a·ω2. It is probably useful to remind ourselves how we get this result so as to make sure our calculations are relativistically correct. The position vector r (which describes the position of the zbw charge) has a horizontal and a vertical component: x = a·cos(ωt) and y = a·sin(ωt). We can now calculate the two components of the (tangential) velocity vector v = dr/dt as vx = –a·ω·sin(ωt) and vy y = –a· ω·cos(ωt) and, in the next step, the components of the (centripetal) acceleration vector ac: ax = –a·ω2·cos(ωt) and ay = –a·ω2·sin(ωt). The magnitude of this vector is then calculated as follows: