Pre-scriptum (dated 26 June 2020): This post suffered from the DMCA take-down of material from Feynman’s Lectures, so some graphs are lacking and the layout was altered as a result. In any case, I now think the distinction between bosons and fermions is one of the most harmful scientific myths in physics. I deconstructed quite a few myths in my realist interpretation of QM, but I focus on this myth in particular in this paper: Feynman’s Worst Jokes and the Boson-Fermion Theory.

Original post:

Probability amplitudes: what are they?

Instead of reading Penrose, I’ve started to read Richard Feynman again. Of course, reading the original is always better than whatever others try to make of that, so I’d recommend you read Feynman yourself – instead of this blog. But then you’re doing that already, aren’t you? 🙂

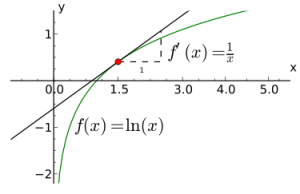

Let’s explore those probability amplitudes somewhat more. They are complex numbers. In a fine little book on quantum mechanics (QED, 1985), Feynman calls them ‘arrows’ – and that’s what they are: two-dimensional vectors, aka complex numbers. So they have a direction and a length (or magnitude). When talking amplitudes, the direction and length are known as the phase and the modulus (or absolute value) respectively and you also know by now that the modulus squared represents a probability or probability density, such as the probability of detecting some particle (a photon or an electron) at some location x or some region Δx, or the probability of some particle going from A to B, or the probability of a photon being emitted or absorbed by an electron (or a proton), etcetera. I’ve inserted two illustrations below to explain the matter.

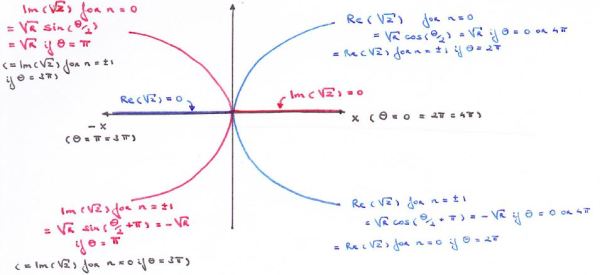

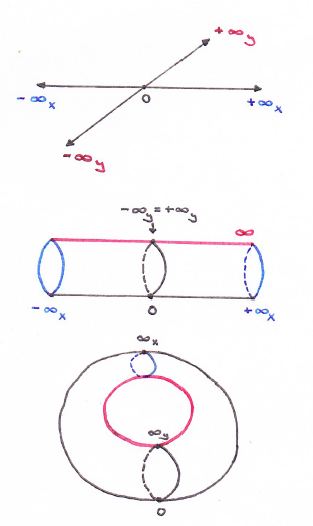

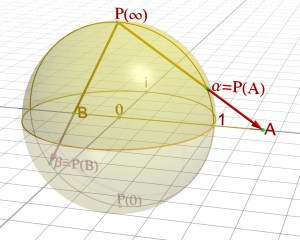

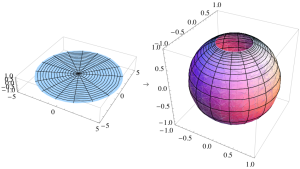

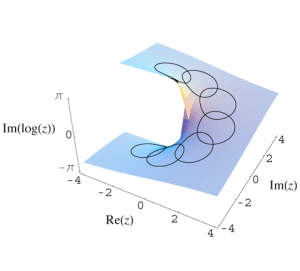

The first illustration just shows what a complex number really is: a two-dimensional number (z) with a real part (Re(z) = x) and an imaginary part (Im(z) = y). We can represent it in two ways: one uses the (x, y) coordinate system (z = x + iy), and the other is the so-called polar form: z = reiφ. The (real) number e in the latter equation is just Euler’s number, so that’s a mathematical constant (just like π). The little i is the imaginary unit, so that’s the thing we introduce to add a second (vertical) dimension to our analysis: i can be written as 0+i = (0, 1) indeed, and so it’s like a (second) basis vector in the two-dimensional (Cartesian or complex) plane.

I should not say much more about this, but I must list some essential properties and relationships:

- The coordinate and polar form are related through Euler’s formula: z = x + iy = reiφ = r(cosφ + isinφ).

- From this, and the fact that cos(-φ) = cosφ and sin(-φ) = –sinφ, it follows that the (complex) conjugate z* = x – iy of a complex number z = x + iy is equal to z* = re–iφ. [I use z* as a symbol, instead of z-bar, because I can’t find a z-bar in the character set here.] This equality is illustrated above.

- The length/modulus/absolute value of a complex number is written as |z| and is equal to |z| = (x2 + y2)1/2 = |reiφ| = r (so r is always a positive (real) number).

- As you can see from the graph, a complex number z and its conjugate z* have the same absolute value: |z| = |x+iy| = |z*| = |x-iy|.

- Therefore, we have the following: |z||z|=|z*||z*|=|z||z*|=|z|2, and we can use this result to calculate the (multiplicative) inverse: z-1 = 1/z = z*/|z|2.

- The absolute value of a product of complex numbers equals the product of the absolute values of those numbers: |z1z2| = |z1||z2|.

- Last but not least, it is important to be aware of the geometric interpretation of the sum and the product of two complex numbers:

- The sum of two complex numbers amounts to adding vectors, so that’s the familiar parallelogram law for vector addition: (a+ib) + (c+id) = (a+b) + i(c+d).

- Multiplying two complex numbers amounts to adding the angles and multiplying their lengths – as evident from writing such product in its polar form: reiθseiΘ = rsei(θ+Θ). The result is, quite obviously, another complex number. So it is not the usual scalar or vector product which you may or may not be familiar with.

[For the sake of completeness: (i) the scalar product (aka dot product) of two vectors (a•b) is equal to the product of is the product of the magnitudes of the two vectors and the cosine of the angle between them: a•b = |a||b|cosα; and (ii) the result of a vector product (or cross product) is a vector which is perpendicular to both, so it’s a vector that is not in the same plane as the vectors we are multiplying: a×b = |a||b| sinα n, with n the unit vector perpendicular to the plane containing a and b in the direction given by the so-called right-hand rule. Just be aware of the difference.]

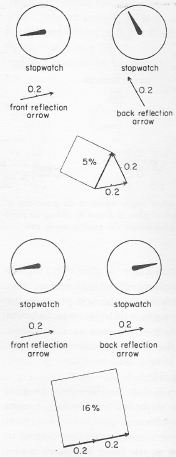

The second illustration (see below) comes from that little book I mentioned above already: Feynman’s exquisite 1985 Alix G. Mautner Memorial Lectures on Quantum Electrodynamics, better known as QED: the Strange Theory of Light and Matter. It shows how these probability amplitudes, or ‘arrows’ as he calls them, really work, without even mentioning that they are ‘probability amplitudes’ or ‘complex numbers’. That being said, these ‘arrows’ are what they are: probability amplitudes.

To be precise, the illustration below shows the probability amplitude of a photon (so that’s a little packet of light) reflecting from the front surface (front reflection arrow) and the back (back reflection arrow) of a thin sheet of glass. If we write these vectors in polar form (reiφ), then it is obvious that they have the same length (r = 0.2) but their phase φ is different. That’s because the photon needs to travel a bit longer to reach the back of the glass: so the phase varies as a function of time and space, but the length doesn’t. Feynman visualizes that with the stopwatch: as the photon is emitted from a light source and travels through time and space, the stopwatch turns and, hence, the arrow will point in a different direction.

[To be even more precise, the amplitude for a photon traveling from point A to B is a (fairly simple) function (which I won’t write down here though) which depends on the so-called spacetime interval. This spacetime interval (written as I or s2) is equal to I = [(x2 -x1)2+(y2 -y1)2+(z2 -z1)2] – (t2 -t1)2. So the first term in this expression is the square of the distance in space, and the second term is the difference in time, or the ‘time distance’. Of course, we need to measure time and distance in equivalent units: we do that either by measuring spatial distance in light-seconds (i.e. the distance traveled by light in one second) or by expressing time in units that are equal to the time it takes for light to travel one meter (in the latter case we ‘stretch’ time (by multiplying it with c, i.e. the speed of light) while in the former, we ‘stretch’ our distance units). Because of the minus sign between the two terms, the spacetime interval can be negative, zero, or positive, and we call these intervals time-like (I < 0), light-like (I = 0) or space-like (I > 0). Because nothing travels faster than light, two events separated by a space-like interval cannot have a cause-effect relationship. I won’t go into any more detail here but, at this point, you may want to read the article on the so-called light cone relating past and future events in Wikipedia, because that’s what we’re talking about here really.]

Feynman adds the two arrows, because a photon may be reflected either by the front surface or by the back surface and we can’t know which of the two possibilities was the case. So he adds the amplitudes here, not the probabilities. The probability of the photon bouncing off the front surface is the modulus of the amplitude squared, (i.e. |reiφ|2 = r2), and so that’s 4% here (0.2·0.2). The probability for the back surface is the same: 4% also. However, the combined probability of a photon bouncing back from either the front or the back surface – we cannot know which path was followed – is not 8%, but some value between 0 and 16% (5% only in the top illustration, and 16% (i.e. the maximum) in the bottom illustration). This value depends on the thickness of the sheet of glass. That’s because it’s the thickness of the sheet that determines where the hand of our stopwatch stops. If the glass is just thick enough to make the stopwatch make one extra half turn as the photon travels through the glass from the front to the back, then we reach our maximum value of 16%, and so that’s what shown in the bottom half of the illustration above.

For the sake of completeness, I need to note that the full explanation is actually a bit more complex. Just a little bit. 🙂 Indeed, there is no such thing as ‘surface reflection’ really: a photon has an amplitude for scattering by each and every layer of electrons in the glass and so we have actually have many more arrows to add in order to arrive at a ‘final’ arrow. However, Feynman shows how all these arrows can be replaced by two so-called ‘radius arrows’: one for ‘front surface reflection’ and one for ‘back surface reflection’. The argument is relatively easy but I have no intention to fully copy Feynman here because the point here is only to illustrate how probabilities are calculated from probability amplitudes. So just remember: probabilities are real numbers between 0 and 1 (or between 0 and 100%), while amplitudes are complex numbers – or ‘arrows’ as Feynman calls them in this popular lectures series.

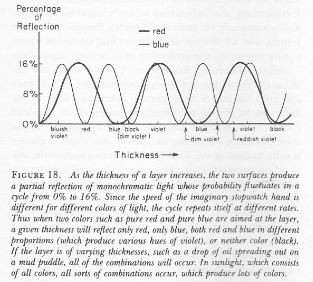

In order to give somewhat more credit to Feynman – and also to be somewhat more complete on how light really reflects from a sheet of glass (or a film of oil on water or a mud puddle), I copy one more illustration here – with the text – which speaks for itself: “The phenomenon of colors produced by the partial reflection of white light by two surfaces is called iridescence, and can be found in many places. Perhaps you have wondered how the brilliant colors of hummingbirds and peacocks are produced. Now you know.” The iridescence phenomenon is caused by really small variations in the thickness of the reflecting material indeed, and it is, perhaps, worth noting that Feynman is also known as the father of nanotechnology… 🙂

Light versus matter

So much for light – or electromagnetic waves in general. They consist of photons. Photons are discrete wave-packets of energy, and their energy (E) is related to the frequency of the light (f) through the Planck relation: E = hf. The factor h in this relation is the Planck constant, or the quantum of action in quantum mechanics as this tiny number (6.62606957×10−34) is also being referred to. Photons have no mass and, hence, they travel at the speed of light indeed. But what about the other wave-like particles, like electrons?

For these, we have probability amplitudes (or, more generally, a wave function) as well, the characteristics of which are given by the de Broglie relations. These de Broglie relations also associate a frequency and a wavelength with the energy and/or the momentum of the ‘wave-particle’ that we are looking at: f = E/h and λ = h/p. In fact, one will usually find those two de Broglie relations in a slightly different but equivalent form: ω = E/ħ and k = p/ħ. The symbol ω stands for the angular frequency, so that’s the frequency expressed in radians. In other words, ω is the speed with which the hand of that stopwatch is going round and round and round. Similarly, k is the wave number, and so that’s the wavelength expressed in radians (or the spatial frequency one might say). We use k and ω in wave functions because the argument of these wave functions is the phase of the probability amplitude, and this phase is expressed in radians. For more details on how we go from distance and time units to radians, I refer to my previous post. [Indeed, I need to move on here otherwise this post will become a book of its own! Just check out the following: λ = 2π/k and f = ω/2π.]

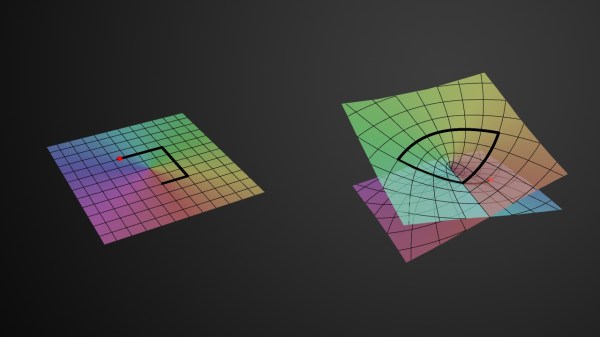

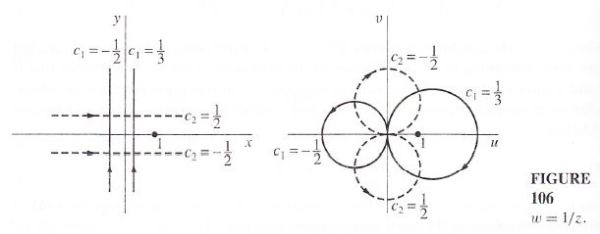

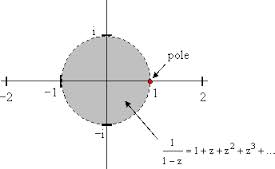

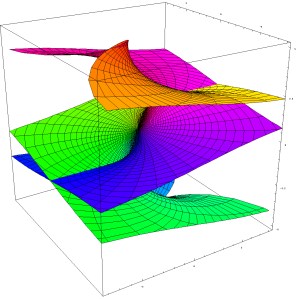

How should we visualize a de Broglie wave for, let’s say, an electron? Well, I think the following illustration (which I took from Wikipedia) is not too bad.

Let’s first look at the graph on the top of the left-hand side of the illustration above. We have a complex wave function Ψ(x) here but only the real part of it is being graphed. Also note that we only look at how this function varies over space at some fixed point of time, and so we do not have a time variable here. That’s OK. Adding the complex part would be nice but it would make the graph even more ‘complex’ :-), and looking at one point in space only and analyzing the amplitude as a function of time only would yield similar graphs. If you want to see an illustration with both the real as well as the complex part of a wave function, have a look at my previous post.

We also have the probability – that’s the red graph – as a function of the probability amplitude: P = |Ψ(x)|2 (so that’s just the modulus squared). What probability? Well, the probability that we can actually find the particle (let’s say an electron) at that location. Probability is obviously always positive (unlike the real (or imaginary) part of the probability amplitude, which oscillate around the x-axis). The probability is also reflected in the opacity of the little red ‘tennis ball’ representing our ‘wavicle’: the opacity varies as a function of the probability. So our electron is smeared out, so to say, over the space denoted as Δx.

Δx is the uncertainty about the position. The question mark next to the λ symbol (we’re still looking at the graph on the top left-hand side of the above illustration only: don’t look at the other three graphs now!) attributes this uncertainty to uncertainty about the wavelength. As mentioned in my previous post, wave packets, or wave trains, do not tend to have an exact wavelength indeed. And so, according to the de Broglie equation λ = h/p, if we cannot associate an exact value with λ, we will not be able to associate an exact value with p. Now that’s what’s shown on the right-hand side. In fact, because we’ve got a relatively good take on the position of this ‘particle’ (or wavicle we should say) here, we have a much wider interval for its momentum : Δpx. [We’re only considering the horizontal component of the momentum vector p here, so that’s px.] Φ(p) is referred to as the momentum wave function, and |Φ(p)|2 is the corresponding probability (or probability density as it’s usually referred to).

The two graphs at the bottom present the reverse situation: fairly precise momentum, but a lot of uncertainty about the wavicle’s position (I know I should stick to the term ‘particle’ – because that’s what physicists prefer – but I think ‘wavicle’ describes better what it’s supposed to be). So the illustration above is not only an illustration of the de Broglie wave function for a particle, but it also illustrates the Uncertainty Principle.

Now, I know I should move on to the thing I really want to write about in this post – i.e. bosons and fermions – but I feel I need to say a few things more about this famous ‘Uncertainty Principle’ – if only because I find it quite confusing. According to Feynman, one should not attach too much importance to it. Indeed, when introducing his simple arithmetic on probability amplitudes, Feynman writes the following about it: “The uncertainty principle needs to be seen in its historical context. When the revolutionary ideas of quantum physics were first coming out, people still tried to understand them in terms of old-fashioned ideas (such as, light goes in straight lines). But at a certain point, the old-fashioned ideas began to fail, so a warning was developed that said, in effect, ‘Your old-fashioned ideas are no damn good when…’ If you get rid of all the old-fashioned ideas and instead use the ideas that I’m explaining in these lectures – adding arrows for all the ways an event can happen – there is no need for the uncertainty principle!” So, according to Feynman, wave function math deals with all and everything and therefore we should, perhaps, indeed forget about this rather mysterious ‘principle’.

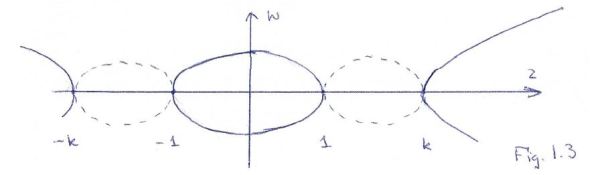

However, because it is mentioned so much (especially in the more popular writing), I did try to find some kind of easy derivation of its standard formulation: ΔxΔp ≥ ħ (ħ = h/2π, i.e. the quantum of angular momentum in quantum mechanics). To my surprise, it’s actually not easy to derive the uncertainty principle from other basic ‘principles’. As mentioned above, it follows from the de Broglie equation λ = h/p that momentum (p) and wavelength (λ) are related, but so how do we relate the uncertainty about the wavelength (Δλ) or the momentum (Δp) to the uncertainty about the position of the particle (Δx)? The illustration below, which analyzes a wave packet (aka a wave train), might provide some clue. Before you look at the illustration and start wondering what it’s all about, remember that a wave function with a definite (angular) frequency ω and wave number k (as described in my previous post), which we can write as Ψ = Aei(ωt-k•x), represents the amplitude of a particle with a known momentum p = ħ/k at some point x and t, and that we had a big problem with such wave, because the squared modulus of this function is a constant: |Ψ|2 = |Aei(ωt-k•x)|2 = A2. So that means that the probability of finding this particle is the same at all points. So it’s everywhere and nowhere really (so it’s like the second wave function in the illustration above, but then with Δx infinitely long and the same wave shape all along the x-axis). Surely, we can’t have this, can we? Now we cannot – if only because of the fact that if we add up all of the probabilities, we would not get some finite number. So, in reality, particles are effectively confined to some region Δx or – if we limit our analysis to one dimension only (for the sake of simplicity) – Δx (remember that bold-type symbols represent vectors). So the probability amplitude of a particle is more likely to look like something that we refer to as a wave packet or a wave train. And so that’s what’s explained more in detail below.

Now, I said that localized wave trains do not tend to have an exact wavelength. What do I mean with that? It doesn’t sound very precise, does it? In fact, we actually can easily sketch a graph of a wave packet with some fixed wavelength (or fixed frequency), so what am I saying here? I am saying that, in quantum physics, we are only looking at a very specific type of wave train: they are a composite of a (potentially infinite) number of waves whose wavelengths are distributed more or less continuously around some average, as shown in the illustration below, and so the addition of all of these waves – or their superposition as the process of adding waves is usually referred to – results in a combined ‘wavelength’ for the localized wave train that we cannot, indeed, equate with some exact number. I have not mastered the details of the mathematical process referred to as Fourier analysis (which refers to the decomposition of a combined wave into its sinusoidal components) as yet, and, hence, I am not in a position to quickly show you how Δx and Δλ are related exactly, but the point to note is that a wider spread of wavelengths results in a smaller Δx. Now, a wider spread of wavelengths corresponds to a wider spread in p too, and so there we have the Uncertainty Principle: the more we know about Δx, the less we know about Δx, and so that’s what the inequality ΔxΔp ≥ h/2π represents really.

[Those who like to check things out may wonder why a wider spread in wavelength implies a wider spread in momentum. Indeed, if we just replace λ and p with Δλ and Δp in the de Broglie equation λ = h/p, we get Δλ = h/Δp and so we have an inversely proportional relationship here, don’t we? No. We can’t just write that Δλ = Δ(h/p) but this Δ is not some mathematical operator than you can simply move inside of the brackets. What is Δλ? Is it a standard deviation? Is it the spread and, if so, what’s the spread? We could, for example, define it as the difference between some maximum value λmax and some minimum value λmin, so as Δλ = λmax – λmin. These two values would then correspond with pmax =h/λmin and pmin =h/λmax and so the corresponding spread in momentum would be equal to Δp = pmax – pmin = h/λmin – h/λmax = h(λmax – λmin)/(λmaxλmin). So a wider spread in wavelength does result in a wider spread in momentum, but the relationship is more subtle than you might think at first. In fact, in a more rigorous approach, we would indeed see the standard deviation (represented by the sigma symbol σ) from some average as a measure of the ‘uncertainty’. To be precise, the more precise formulation of the Uncertainty Principle is: σxσp ≥ ħ/2, but don’t ask me where that 2 comes from!]

I really need to move on now, because this post is already way too lengthy and, hence, not very readable. So, back to that very first question: what’s that wave function math? Well, that’s obviously too complex a topic to be fully exhausted here. 🙂 I just wanted to present one aspect of it in this post: Bose-Einstein statistics. Huh? Yes.

When we say Bose-Einstein statistics, we should also say its opposite: Fermi-Dirac statistics. Bose-Einstein statistics were ‘discovered’ by the Indian scientist Satyanendra Nath Bose (the only thing Einstein did was to give Bose’s work on this wider recognition) and they apply to bosons (so they’re named after Bose only), while Fermi-Dirac statistics apply to fermions (‘Fermi-Diraqions’ doesn’t sound good either obviously). Any particle, or any wavicle I should say, is either a fermion or a boson. There’s a strict dichotomy: you can’t have characteristics of both. No split personalities. Not even for a split second.

The best-known examples of bosons are photons and the recently experimentally confirmed Higgs particle. But, in case you have heard of them, gluons (which mediate the so-called strong interactions between particles), and the W+, W– and Z particles (which mediate the so-called weak interactions) are bosons too. Protons, neutrons and electrons, on the other hand, are fermions.

More complex particles, such as atomic nuclei, are also either bosons or fermions. That depends on the number of protons and neutrons they consist of. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Here, I’ll just note that bosons – unlike fermions – can pile on top of one another without limit, all occupying the same ‘quantum state’. This explains superconductivity, superfluidity and Bose-Einstein condensation at low temperatures. Indeed, these phenomena usually involve (bosonic) helium. You can’t do it with fermions. Superfluid helium has very weird properties, including zero viscosity – so it flows without dissipating energy and it creeps up the wall of its container, seemingly defying gravity: just Google one of the videos on the Web! It’s amazing stuff! Bose statistics also explain why photons of the same frequency can form coherent and extremely powerful laser beams, with (almost) no limit as to how much energy can be focused in a beam.

Fermions, on the other hand, avoid one another. Electrons, for example, organize themselves in shells around a nucleus stack. They can never collapse into some kind of condensed cloud, as bosons can. If electrons would not be fermions, we would not have such variety of atoms with such great range of chemical properties. But, again, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Back to the math.

Bose versus Fermi particles

When adding two probability amplitudes (instead of probabilities), we are adding complex numbers (or vectors or arrows or whatever you want to call them), and so we need to take their phase into account or – to put it simply – their direction. If their phase is the same, the length of the new vector will be equal to the sum of the lengths of the two original vectors. When their phase is not the same, then the new vector will be shorter than the sum of the lengths of the two amplitudes that we are adding. How much shorter? Well, that obviously depends on the angle between the two vectors, i.e. the difference in phase: if it’s 180 degrees (or π radians), then they will cancel each other out and we have zero amplitude! So that’s destructive or negative interference. If it’s less than 90 degrees, then we will have constructive or positive interference.

It’s because of this interference effect that we have to add probability amplitudes first, before we can calculate the probability of an event happening in one or the other (indistinguishable) way (let’s say A or B) – instead of just adding probabilities as we would do in the classical world. It’s not subtle. It makes a big difference: |ΨA + ΨB|2 is the probability when we cannot distinguish the alternatives (so when we’re in the world of quantum mechanics and, hence, we have to add amplitudes), while |ΨA|2 + |ΨB|2 is the probability when we can see what happens (i.e. we can see whether A or B was the case). Now, |ΨA + ΨB|2 is definitely not the same as |ΨA|2 + |ΨB|2 – not for real numbers, and surely not for complex numbers either. But let’s move on with the argument – literally: I mean the argument of the wave function at hand here.

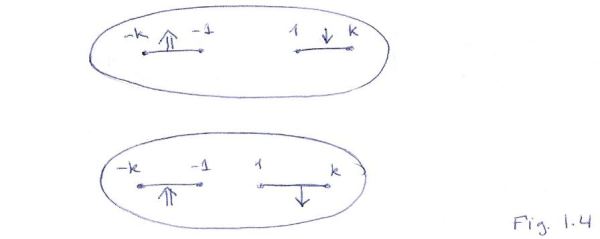

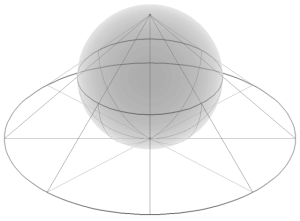

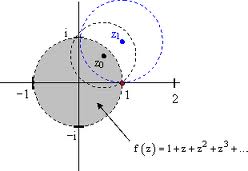

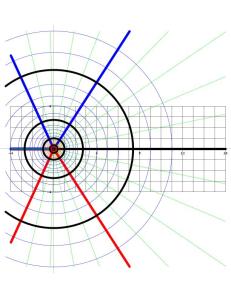

That stopwatch business above makes it easier to introduce the thought experiment which Feynman also uses to introduce Bose versus Fermi statistics (Feynman Lectures (1965), Vol. III, Lecture 4). The experimental set-up is shown below. We have two particles, which are being referred to as particle a and particle b respectively (so we can distinguish the two), heading straight for each other and, hence, they are likely to collide and be scattered in some other direction. The experimental set-up is designed to measure where they are likely to end up, i.e. to measure probabilities. [There’s no certainty in the quantum-mechanical world, remember?] So, in this experiment, we have a detector (or counter) at location 1 and a detector/counter at location 2 and, after many many measurements, we have some value for the (combined) probability that particle a goes to detector 1 and particle b goes to counter 2. This amplitude is a complex number and you may expect it will depend on the angle θ as shown in the illustration below.

So this angle θ will obviously show up somehow in the argument of our wave function. Hence, the wave function, or probability amplitude, describing the amplitude of particle a ending up in counter 1 and particle b ending up in counter 2 will be some (complex) function Ψ1= f(θ). Please note, once again, that θ is not some (complex) phase but some real number (expressed in radians) between 0 and 2π that characterizes the set-up of the experiment above. It is also worth repeating that f(θ) is not the amplitude of particle a hitting detector 1 only but the combined amplitude of particle a hitting counter 1 and particle b hitting counter 2! It makes a big difference and it’s essential in the interpretation of this argument! So, the combined probability of a going to 1 and of particle b going to 2, which we will write as P1, is equal to |Ψ1|2 = |f(θ)|2.

OK. That’s obvious enough. However, we might also find particle a in detector 2 and particle b in detector 1. Surely, the probability amplitude probability for this should be equal to f(θ+π)? It’s just a matter of switching counter 1 and 2 – i.e. we rotate their position over 180 degrees, or π (in radians) – and then we just insert the new angle of this experimental set-up (so that’s θ+π) into the very same wave function and there we are. Right?

Well… Maybe. The probability of a going to 2 and b going to 1, which we will write as P2, will be equal to |f(θ+π)|2 indeed. However, our probability amplitude, which I’ll write as Ψ2, may not be equal to f(θ+π). It’s just a mathematical possibility. I am not saying anything definite here. Huh? Why not?

Well… Think about the thing we said about the phase and the possibility of a phase shift: f(θ+π) is just one of the many mathematical possibilities for a wave function yielding a probability P2 =|Ψ2|2 = |f(θ+π)|2. But any function eiδf(θ+π) will yield the same probability. Indeed, |z1z2| = |z1||z2| and so |eiδ f(θ+π)|2 = (|eiδ||f(θ+π)|)2 = |eiδ|2|f(θ+π)|2 = |f(θ+π)|2 (the square of the modulus of a complex number on the unit circle is always one – because the length of vectors on the unit circle is equal to one). It’s a general thing: if Ψ is some wave function (i.e. it describes some complex amplitude in space and time, then eiδΨ is the same wave function but with a phase shift equal to δ. Huh? Yes. Think about it: we’re multiplying complex numbers here, so that’s adding angles and multiplying lengths. Now the length of eiδ is 1 (because it’s a complex number on the unit circle) but its phase is δ. So multiplying Ψ with eiδ does not change the length of Ψ but it does shift its phase by an amount (in radians) equal to δ. That should be easy enough to understand.

You probably wonder what I am being so fussy, and what that δ could be, or why it would be there. After all, we do have a well-behaved wave function f(θ) here, depending on x, t and θ, and so the only thing we did was to change the angle θ (we added π radians to it). So why would we need to insert a phase shift here? Because that’s what δ really is: some random phase shift. Well… I don’t know. This phase factor is just a mathematical possibility as for now. So we just assume that, for some reason which we don’t understand right now, there might be some ‘arbitrary phase factor’ (that’s how Feynman calls δ) coming into play when we ‘exchange’ the ‘role’ of the particles. So maybe that δ is there, but maybe not. I admit it looks very ugly. In fact, if the story about Bose’s ‘discovery’ of this ‘mathematical possibility’ (in 1924) is correct, then it all started with an obvious ‘mistake’ in a quantum-mechanical calculation – but a ‘mistake’ that, miraculously, gave predictions that agreed with experimental results that could not be explained without introducing this ‘mistake’. So let the argument go full circle – literally – and take your time to appreciate the beauty of argumentation in physics.

Let’s swap detector 1 and detector 2 a second time, so we ‘exchange’ particle a and b once again. So then we need to apply this phase factor δ once again and, because of symmetry in physics, we obviously have to use the same phase factor δ – not some other value γ or something. We’re only rotating our detectors once again. That’s it. So all the rest stays the same. Of course, we also need to add π once more to the argument in our wave function f. In short, the amplitude for this is:

eiδ[eiδf(θ+π+π)] = (eiδ)2 f(θ) = ei2δ f(θ)

Indeed, the angle θ+2π is the same as θ. But so we have twice that phase shift now: 2δ. As ugly as that ‘thing’ above: eiδf(θ+π). However, if we square the amplitude, we get the same probability: P1 = |Ψ1|2 = |ei2δ f(θ)| = |f(θ)|2. So it must be right, right? Yes. But – Hey! Wait a minute! We are obviously back at where we started, aren’t we? We are looking at the combined probability – and amplitude – for particle a going to counter 1 and particle b going to counter 2, and the angle is θ! So it’s the same physical situation, and – What the heck! – reality doesn’t change just because we’re rotating these detectors a couple of times, does it? [In fact, we’re actually doing nothing but a thought experiment here!] Hence, not only the probability but also the amplitude must be the same. So (eiδ)2f(θ) must equal f(θ) and so… Well… If (eiδ)2f(θ) = f(θ), then (eiδ)2 must be equal to 1. Now, what does that imply for the value of δ?

Well… While the square of the modulus of all vectors on the unit circle is always equal to 1, there are only two cases for which the square of the vector itself yields 1: (I) eiδ = eiπ = e–iπ = –1 (check it: (eiπ)2 = (–1)2 = ei2π = ei0 = +1), and (II) eiδ = ei2π = ei0 = e0 = +1 (check it: ei2π)2 = (+1)2 = ei4π = ei0 = +1). In other words, our phase factor δ is either δ = 0 (or 0 ± 2nπ) or, else, δ = π (or π ± 2nπ). So eiδ = ± 1 and Ψ2 is either +f(θ+π) or, else, –f(θ+π). What does this mean? It means that, if we’re going to be adding the amplitudes, then the ‘exchanged case’ may contribute with the same sign or, else, with the opposite sign.

But, surely, there is no need to add amplitudes here, is there? Particle a can be distinguished from particle b and so the first case (particle a going into counter 1 and particle b going into counter 2) is not the same as the ‘exchanged case’ (particle a going into counter 2 and b going into counter 1). So we can clearly distinguish or verify which of the two possible paths are followed and, hence, we should be adding probabilities if we want to get the combined probability for both cases, not amplitudes. Now that is where the fun starts. Suppose that we have identical particles here – so not some beam of α-particles (i.e. helium nuclei) bombarding beryllium nuclei for instance but, let’s say, electrons on electrons, or photons on photons indeed – then we do have to add the amplitudes, not the probabilities, in order to calculate the combined probability of a particle going into counter 1 and the other particle going into counter 2, for the simple reason that we don’t know which is which and, hence, which is going where.

Let me immediately throw in an important qualifier: defining ‘identical particles’ is not as easy as it sounds. Our ‘wavicle’ of choice, for example, an electron, can have its spin ‘up’ or ‘down’ – and so that’s two different things. When an electron arrives in a counter, we can measure its spin (in practice or in theory: it doesn’t matter in quantum mechanics) and so we can distinguish it and, hence, an electron that’s ‘up’ is not identical to one that’s ‘down’. [I should resist the temptation but I’ll quickly make the remark: that’s the reason why we have two electrons in one atomic orbital: one is ‘up’ and the other one is ‘down’. Identical particles need to be in the same ‘quantum state’ (that’s the standard expression for it) to end up as ‘identical particles’ in, let’s say, a laser beam or so. As Feynman states it: in this (theoretical) experiment, we are talking polarized beams, with no mixture of different spin states.]

The wonderful thing in quantum mechanics is that mathematical possibility usually corresponds with reality. For example, electrons with positive charge, or anti-matter in general, is not only a theoretical possibility: they exist. Likewise, we effectively have particles which interfere with positive sign – these are called Bose particles – and particles which interfere with negative sign – Fermi particles.

So that’s reality. The factor eiδ = ± 1 is there, and it’s a strict dichotomy: photons, for example, always behave like Bose particles, and protons, neutrons and electrons always behave like Fermi particles. So they don’t change their mind and switch from one to the other category, not for a short while, and not for a long while (or forever) either. In fact, you may or may not be surprised to hear that there are experiments trying to find out if they do – just in case. 🙂 For example, just Google for Budker and English (2010) from the University of California at Berkeley. The experiments confirm the dichotomy: no split personalities here, not even for a nanosecond (10−9 s), or a picosecond (10−12 s). [A picosecond is the time taken by light to travel 0.3 mm in a vacuum. In a nanosecond, light travels about one foot.]

In any case, does all of this really matter? What’s the difference, in practical terms that is? Between Bose or Fermi, I must assume we prefer the booze.

It’s quite fundamental, however. Hang in there for a while and you’ll see why.

Bose statistics

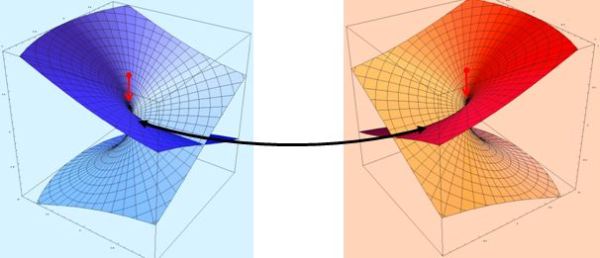

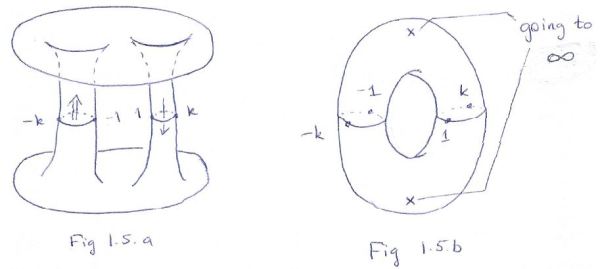

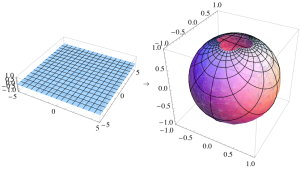

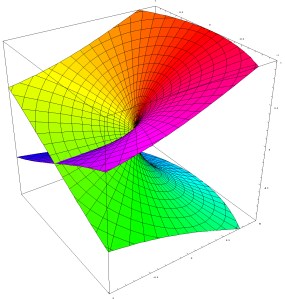

Suppose we have, once again, some particle a and b that (i) come from different directions (but, this time around, not necessarily in the experimental set-up as described above: the two particles may come from any direction really), (ii) are being scattered, at some point in space (but, this time around, not necessarily the same point in space), (iii) end up going in one and the same direction and – hopefully – (iv) arrive together at some other point in space. So they end up in the same state, which means they have the same direction and energy (or momentum) and also whatever other condition that’s relevant. Again, if the particles are not identical, we can catch both of them and identify which is which. Now, if it’s two different particles, then they won’t take exactly the same path. Let’s say they travel along two infinitesimally close paths referred to as path 1 and 2 and so we should have two infinitesimally small detectors: one at location 1 and the other at location 2. The illustration below (credit to Feynman once again!) is for n particles, but here we’ll limit ourselves to the calculations for just two.

Let’s denote the amplitude of a to follow path 1 (and end up in counter 1) as a1, and the amplitude of b to follow path 2 (and end up in counter 2) as b1. Then the amplitude for these two scatterings to occur at the same time is the product of these two amplitudes, and so the probability is equal to |a1b1|2 = [|a1||b1|]2 = |a1|2|b1|2. Similarly, the combined amplitude of a following path 2 (and ending up in counter 2) and b following path 1 (etcetera) is |a2|2|b2|2. But so we said that the directions 1 and 2 were infinitesimally close and, hence, the values for a1 and a2, and for b1 and b2, should also approach each other, so we can equate them with a and b respectively and, hence, the probability of some kind of combined detector picking up both particles as they hit the counter is equal to P = 2|a|2|b|2 (just substitute and add). [Note: For those who would think that separate counters and ‘some kind of combined detector’ radically alter the set-up of this thought experiment (and, hence, that we cannot just do this kind of math), I refer to Feynman (Vol. III, Lecture 4, section 4): he shows how it works using differential calculus.]

Now, if the particles cannot be distinguished – so if we have ‘identical particles’ (like photons, or polarized electrons) – and if we assume they are Bose particles (so they interfere with a positive sign – i.e. like photons, but not like electrons), then we should no longer add the probabilities but the amplitudes, so we get a1b2 + a2b1 = 2ab for the amplitude and – lo and behold! – a probability equal to P = 4|a|2|b|2. So what? Well… We’ve got a factor 2 difference here: 4|a|2|b|2 is two times 2|a|2|b|2.

This is a strange result: it means we’re twice as likely to find two identical Bose particles scattered into the same state as you would assuming the particles were different. That’s weird, to say the least. In fact, it gets even weirder, because this experiment can easily be extended to a situation where we have n particles present (which is what the illustration suggests), and that makes it even more interesting (more ‘weird’ that is). I’ll refer to Feynman here for the (fairly easy but somewhat lengthy) calculus in case we have n particles, but the conclusion is rock-solid: if we have n bosons already present in some state, then the probability of getting one extra boson is n+1 times greater than it would be if there were none before.

So the presence of the other particles increases the probability of getting one more: bosons like to crowd. And there’s no limit to it: the more bosons you have in one space, the more likely it is another one will want to occupy the same space. It’s this rather weird phenomenon which explains equally weird things such as superconductivity and superfluidity, or why photons of the same frequency can form such powerful laser beams: they don’t mind being together – literally on the same spot – in huge numbers. In fact, they love it: a laser beam, superfluidity or superconductivity are actually quantum-mechanical phenomena that are visible at a macro-scale.

OK. I won’t go into any more detail here. Let me just conclude by showing how interference works for Fermi particles. Well… That doesn’t work or, let me be more precise, it leads to the so-called (Pauli) Exclusion Principle which, for electrons, states that “no two electrons can be found in exactly the same state (including spin).” Indeed, we get a1b2 – a2b1= ab – ab = 0 (zero!) if we let the values of a1 and a2, and b1 and b2, come arbitrarily close to each other. So the amplitude becomes zero as the two directions (1 and 2) approach each other. That simply means that it is not possible at all for two electrons to have the same momentum, location or, in general, the same state of motion – unless they are spinning opposite to each other (in which case they are not ‘identical’ particles). So what? Well… Nothing much. It just explains all of the chemical properties of atoms. 🙂

In addition, the Pauli exclusion principle also explains the stability of matter on a larger scale: protons and neutrons are fermions as well, and so they just “don’t get close together with one big smear of electrons around them”, as Feynman puts it, adding: “Atoms must keep away from each other, and so the stability of matter on a large scale is really a consequence of the Fermi particle nature of the electrons, protons and neutrons.”

Well… There’s nothing much to add to that, I guess. 🙂

Post scriptum:

I wrote that “more complex particles, such as atomic nuclei, are also either bosons or fermions”, and that this depends on the number of protons and neutrons they consist of. In fact, bosons are, in general, particles with integer spin (0 or 1), while fermions have half-integer spin (1/2). Bosonic Helium-4 (He4) has zero spin. Photons (which mediate electromagnetic interactions), gluons (which mediate the so-called strong interactions between particles), and the W+, W– and Z particles (which mediate the so-called weak interactions) all have spin one (1). As mentioned above, Lithium-7 (Li7) has half-integer spin (3/2). The underlying reason for the difference in spin between He4 and Li7 is their composition indeed: He4 consists of two protons and two neutrons, while Li7 consists of three protons and four neutrons.

However, we have to go beyond the protons and neutrons for some better explanation. We now know that protons and neutrons are not ‘fundamental’ any more: they consist of quarks, and quarks have a spin of 1/2. It is probably worth noting that Feynman did not know this when he wrote his Lectures in 1965, although he briefly sketches the findings of Murray Gell-Man and Georg Zweig, who published their findings in 1961 and 1964 only, so just a little bit before, and describes them as ‘very interesting’. I guess this is just another example of Feynman’s formidable intellect and intuition… In any case, protons and neutrons are so-called baryons: they consist of three quarks, as opposed to the short-lived (unstable) mesons, which consist of one quark and one anti-quark only (you may not have heard about mesons – they don’t live long – and so I won’t say anything about them). Now, an uneven number of quarks result in half-integer spin, and so that’s why protons and neutrons have half-integer spin. An even number of quarks result in integer spin, and so that’s why mesons have spin zero 0 or 1. Two protons and two neutrons together, so that’s He4, can condense into a bosonic state with spin zero, because four half-integer spins allows for an integer sum. Seven half-integer spins, however, cannot be combined into some integer spin, and so that’s why Li7 has half-integer spin (3/2). Electrons also have half-integer spin (1/2) too. So there you are.

Now, I must admit that this spin business is a topic of which I understand little – if anything at all. And so I won’t go beyond the stuff I paraphrased or quoted above. The ‘explanation’ surely doesn’t ‘explain’ this fundamental dichotomy between bosons and fermions. In that regard, Feynman’s 1965 conclusion still stands: “It appears to be one of the few places in physics where there is a rule which can be stated very simply, but for which no one has found a simple and easy explanation. The explanation is deep down in relativistic quantum mechanics. This probably means that we do not have a complete understanding of the fundamental principle involved. For the moment, you will just have to take it as one of the rules of the world.”

Some content on this page was disabled on June 20, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from Michael A. Gottlieb, Rudolf Pfeiffer, and The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here:

https://wordpress.com/support/copyright-and-the-dmca/

Some content on this page was disabled on June 20, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from Michael A. Gottlieb, Rudolf Pfeiffer, and The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here: