I have just republished one of my long-standing papers on de Broglie’s matter-wave concept as a new, standalone publication, with its own DOI:

👉 De Broglie’s matter-wave concept and issues

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/399225854_De_Broglie’s_matter-wave_concept_and_issues

DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.30104.25605

The reason for republishing is not cosmetic. A new Annex was added on 31 December 2025 that fundamentally clarified — for me, at least — what Schrödinger’s equation is really doing, and just as importantly, what it is not doing.

This clarification came out of a long and at times uncomfortable dialogue with the most recent version of OpenAI’s GPT model (ChatGPT 5.2). Uncomfortable, because it initially destabilized a view I had held for years. Productive, because it forced a deeper structural distinction that I now believe is unavoidable. Let me explain.

The uncomfortable admission: I was wrong about the factor

For a long time, I was convinced that the factor factor in Schrödinger’s equation — especially in the hydrogen atom problem — must reflect some deeper pairing mechanism. At times, I even wondered whether the equation was implicitly modeling an electron pair (opposite spin), rather than a single electron.

That intuition was not random. It came from a broader realist programme in which I treat the electron as a structured object, with internal dynamics (zitterbewegung-like orbital motion), not as a point particle. If mass, energy, and phase all have internal structure, why should a simple quadratic kinetic term with a mysterious be fundamental?

The hard truth is this: that intuition was misplaced — but it was pointing in the right direction.

The mistake was not questioning the factor . The mistake was assuming Schrödinger’s equation was trying to describe everything at once.

The key insight: Schrödinger describes the envelope, not the engine

The decisive realization was structural:

Schrödinger’s wavefunction does not describe the electron’s internal dynamics.

It describes the translational envelope of phase coherence.

Once you see that, several things fall into place immediately:

- The hydrogen “orbitals” are not literal orbits, and not internal electron motion.

- They are standing-wave solutions of an envelope phase, constrained by a Coulomb potential.

- The factor is not mysterious at all at this level: it is the natural coefficient that appears in effective, averaged, quadratic envelope dynamics.

In other words:

The factor belongs to the envelope layer, not to the internal structure of the electron.

My earlier “electron pair” idea tried to explain a structural feature by inventing new ontology. The correct move was simpler and more radical: separate the layers.

One symbol, too many jobs

Modern quantum mechanics makes a profound — and in my view costly — simplification:

It uses one symbol, ψ, to represent:

- internal phase,

- translational dynamics,

- probability amplitudes,

- and experimental observables.

That compression works operationally, but it hides structure.

What the new Annex makes explicit is that Nature almost certainly does not work that way. At minimum, we should distinguish:

- Internal phase

Real, physical, associated with internal orbital motion and energy bookkeeping. - Envelope phase

Slow modulation across space, responsible for interference, diffraction, and spectra. - Observables

What experiments actually measure, which are sensitive mainly to envelope-level phase differences.

Once this distinction is made, long-standing confusions dissolve rather than multiply.

Why this does not contradict experiments

This is crucial.

Nothing in this reinterpretation invalidates:

- electron diffraction,

- hydrogen spectra,

- interference experiments,

- or the empirical success of standard quantum mechanics.

On the contrary: it explains why Schrödinger’s equation works so well — within its proper domain.

The equation is not wrong.

It is just over-interpreted.

A personal note on changing one’s mind

I’ll be honest: this line of reasoning initially felt destabilizing. It challenged a position I had defended for years. But that discomfort turned out to be a feature, not a bug.

Good theory-building does not preserve intuitions at all costs. It preserves structure, coherence, and explanatory power.

What emerged is a cleaner picture:

- internal realism without metaphysics,

- Schrödinger demoted from “ultimate truth” to “effective envelope theory”,

- and a much clearer map of where different mathematical tools belong.

That, to me, is progress.

Where this opens doors

Once we accept that one wavefunction cannot represent all layers of Nature, new possibilities open up:

- clearer interpretations of spin and the Dirac equation,

- better realist models of lattice propagation,

- a more honest treatment of “quantum mysteries” as category mistakes,

- and perhaps new mathematical frameworks that respect internal structure from the start.

Those are not promises — just directions.

For now, I am satisfied that one long-standing conceptual knot has been untied.

And sometimes, that’s enough for a good year’s work. 🙂

Post Scriptum: On AI, Intellectual Sparring, and the Corridor

A final remark, somewhat orthogonal to physics.

The revision that led to this blog post and the accompanying paper did not emerge from a sudden insight, nor from a decisive experimental argument. It emerged from a long, occasionally uncomfortable dialogue with an AI system, in which neither side “won,” but both were forced to refine their assumptions.

At the start of that dialogue, the AI responded in a largely orthodox way, reproducing standard explanations for the factor in Schrödinger’s equation. I, in turn, defended a long-held intuition that this factor must point to internal structure or pairing. What followed was not persuasion, but sparring: resistance on both sides, followed by a gradual clarification of conceptual layers. The breakthrough came when it became clear that a single mathematical object — the wavefunction — was being asked to do too many jobs at once.

From that moment on, the conversation shifted from “who is right?” to “which layer are we talking about?” The result was not a victory for orthodoxy or for realism, but a structural separation: internal phase versus translational envelope, engine versus modulation. That separation resolved a tension that had existed for years in my own thinking.

I have explored this mode of human–AI interaction more systematically in a separate booklet on ResearchGate, where I describe such exchanges as occurring within a corridor: a space in which disagreement does not collapse into dominance or deference, but instead forces both sides toward finer distinctions and more mature reasoning.

This episode convinced me that the real intellectual value of AI does not lie in answers, but in sustained resistance without ego — and in the willingness of the human interlocutor to tolerate temporary destabilization without retreating into dogma. When that corridor holds, something genuinely new can emerge.

In that sense, this post is not only about Schrödinger’s equation. It is also about how thinking itself may evolve when humans and machines are allowed to reason together, rather than merely agree.

Readers interested in this kind of human–AI interaction beyond the present physics discussion may want to look at that separate booklet I published on ResearchGate (≈100 pages), in which I try to categorize different modes of AI–human intellectual interaction — from superficial compliance and authority projection to genuine sparring. In that text, exchanges like the one briefly alluded to above are described as a Type-D collapse: a situation in which both human and AI are forced to abandon premature explanatory closure, without either side “winning,” and where progress comes from structural re-layering rather than persuasion.

The booklet is intentionally exploratory and occasionally playful in tone, but it grew out of exactly this kind of experience: moments where resistance, rather than agreement, turns out to be the most productive form of collaboration.

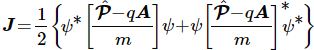

It says that the amplitude for a particle to go from a to b in a vector potential (think of a classical magnetic field) is the amplitude for the same particle to go from a to b when there is no field (A = 0) multiplied by the exponential of the line integral of the vector potential times the electric charge divided by Planck’s constant. I stared at this for quite a while, but then I recognized the formula for the magnetic effect on an amplitude, which I described in

It says that the amplitude for a particle to go from a to b in a vector potential (think of a classical magnetic field) is the amplitude for the same particle to go from a to b when there is no field (A = 0) multiplied by the exponential of the line integral of the vector potential times the electric charge divided by Planck’s constant. I stared at this for quite a while, but then I recognized the formula for the magnetic effect on an amplitude, which I described in