Important post script (PS) – dated 22 December 2018: Dear readers of this post, this is one of the more popular posts of my blog but − in the meanwhile − I did move on, and quite a bit, actually! The analysis below is not entirely consistent: I got many questions on it, and I have been thinking differently as a result. The Q&A below sums up everything: I do think of the photon as a pointlike particle now, and Chapter VIII of my book sums up the photon model. At the same time, if you are really interested in this question – how should one think of a photon? – then it’s probably good you also read the original post. If anything, it shows you how easy it is to get confused.

Hi Brian – see section III of this paper: http://vixra.org/pdf/1812.0273v2.pdf

Feynman’s classical idea of an atomic oscillator is fine in the context of the blackbody radiation problem, but his description of the photon as a long wavetrain does not make any sense. A photon has to pack two things: (1) the energy difference between the Bohr orbitals and (2) Planck’s constant h, which is the (physical) action associated with one cycle of an oscillation (so it’s a force over a distance (the loop or the radius – depending on the force you’re looking at) over a cycle time). See section V of the paper for how the fine-structure constant pops up here – it’s, as usual, a sort of scaling constant, but this time it scales a force. In any case, the idea is that we should think of a photon as one cycle – rather than a long wavetrain. The one cycle makes sense: when you calculate field strength and force you get quite moderate values (not the kind of black-hole energy concentrations some people suggest). It also makes sense from a logical point of view: the wavelength is something real, and so we should think of the photon amplitude (the electric field strength) as being real as well – especially when you think of how that photon is going to interact or be absorbed into another atom.

Sorry for my late reply. It’s been a while since I checked the comments. Please let me know if this makes sense. I’ll have a look at your blog in the coming days. I am working on a new paper on the anomalous magnetic moment – which is not anomalous as all if you start to think about how things might be working in reality. After many years of study, I’ve come to the conclusion that quantum mechanics is a nice way of describing things, but it doesn’t help us in terms of understanding anything. When we want to understand something, we need to push the classical framework a lot further than we currently do. In any case, that’s another discussion.

JL

OK. Now you can move on to the post itself. 🙂 Sorry if this is confusing the reader, but it is necessary to warn him. I think of this post now as still being here to document the history of my search for a ‘basic version of truth’, as someone called it. [For an even more recent update, see Chapter 8 of my book, A Realist Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics.

Original post:

Photons are weird. All elementary particles are weird. As Feynman puts it, in the very first paragraph of his Lectures on Quantum Mechanics : “Historically, the electron, for example, was thought to behave like a particle, and then it was found that in many respects it behaved like a wave. So it really behaves like neither. Now we have given up. We say: “It is like neither. There is one lucky break, however—electrons behave just like light. The quantum behavior of atomic objects (electrons, protons, neutrons, photons, and so on) is the same for all, they are all “particle waves,” or whatever you want to call them. So what we learn about the properties of electrons will apply also to all “particles,” including photons of light.” (Feynman’s Lectures, Vol. III, Chapter 1, Section 1)

I wouldn’t dare to argue with Feynman, of course, but… What? Well… Photons are like electrons, and then they are not. Obviously not, I’d say. For starters, photons do not have mass or charge, and they are also bosons, i.e. ‘force-carriers’ (as opposed to matter-particles), and so they obey very different quantum-mechanical rules, which are referred to as Bose-Einstein statistics. I’ve written about that in other post (see, for example, my post on Bose-Einstein and Fermi-Dirac statistics), so I won’t do that again here. It’s probably sufficient to remind the reader that these rules imply that the so-called Pauli exclusion principle does not apply to them: bosons like to crowd together, thereby occupying the same quantum state—unlike their counterparts, the so-called fermions or matter-particles: quarks (which make up protons and neutrons) and leptons (including electrons and neutrinos), which can’t do that. Two electrons, for example, can only sit on top of each other (or be very near to each other, I should say) if their spins are opposite (so that makes their quantum state different), and there’s no place whatsoever to add a third one because there are only two possible ‘directions’ for the spin: up or down.

From all that I’ve been writing so far, I am sure you have some kind of picture of matter-particles now, and notably of the electron: it’s not really point-like, because it has a so-called scattering cross-section (I’ll say more about this later), and we can find it somewhere taking into account the Uncertainty Principle, with the probability of finding it at point x at time t given by the absolute square of a so-called ‘wave function’ Ψ(x, t).

But what about the photon? Unlike quarks or electrons, they are really point-like, aren’t they? And can we associate them with a psi function too? I mean, they have a wavelength, obviously, which is given by the Planck-Einstein energy-frequency relation: E = hν, with h the Planck constant and ν the frequency of the associated ‘light’. But an electromagnetic wave is not like a ‘probability wave’. So… Do they have a de Broglie wavelength as well?

Before answering that question, let me present that ‘picture’ of the electron once again.

The wave function for electrons

The electron ‘picture’ can be represented in a number of ways but one of the more scientifically correct ones – whatever that means – is that of a spatially confined wave function representing a complex quantity referred to as the probability amplitude. The animation below (which I took from Wikipedia) visualizes such wave functions. As mentioned above, the wave function is usually represented by the Greek letter psi (Ψ), and it is often referred to as a ‘probability wave’ – by bloggers like me, that is 🙂 – but that term is quite misleading. Why? You surely know that by now: the wave function represents a probability amplitude, not a probability. [So, to be correct, we should say a ‘probability amplitude wave’, or an ‘amplitude wave’, but so these terms are obviously too long and so they’ve been dropped and everybody talks about ‘the’ wave function now, although that’s confusing too, because an electromagnetic wave is a ‘wave function’ too, but describing ‘real’ amplitudes, not some weird complex numbers referred to as ‘probability amplitudes’.]

Having said what I’ve said above, probability amplitude and probability are obviously related: if we take the (absolute) square of the psi function – i.e. if we take the (absolute) square of all these amplitudes Ψ(x, t) – then we get the actual probability of finding that electron at point x at time t. So then we get the so-called probability density functions, which are shown on the right-hand side of the illustration above. [As for the term ‘absolute’ square, the absolute square is the squared norm of the associated ‘vector’. Indeed, you should note that the square of a complex number can be negative as evidenced, for example, by the definition of i: i2 = –1. In fact, if there’s only an imaginary part, then its square is always negative. Probabilities are real numbers between 0 and 1, and so they can’t be negative, and so that’s why we always talk about the absolute square, rather than the square as such.]

Below, I’ve inserted another image, which gives a static picture (i.e. one that is not varying in time) of the wave function of a real-life electron. To be precise: it’s the wave function for an electron on the 5d orbital of a hydrogen orbital. You can see it’s much more complicated than those easy things above. However, the idea behind is the same. We have a complex-valued function varying in space and in time. I took it from Wikipedia and so I’ll just copy the explanation here: “The solid body shows the places where the electron’s probability density is above a certain value (0.02), as calculated from the probability amplitude.” What about these colors? Well… The image uses the so-called HSL color system to represent complex numbers: each complex number is represented by a unique color, with a different hue (H), saturation (S) and lightness (L). Just google if you want to know how that works exactly.

OK. That should be clear enough. I wanted to talk about photons here. So let’s go for it. Well… Hmm… I realize I need to talk about some more ‘basics’ first. Sorry for that.

The Uncertainty Principle revisited (1)

The wave function is usually given as a function in space and time: Ψ = Ψ(x, t). However, I should also remind you that we have a similar function in the ‘momentum space’: if ψ is a psi function, then the function in the momentum space is a phi function, and we’ll write it as Φ = Φ(p, t). [As for the notation, x and p are written with capital letters and, hence, represent (three-dimensional) vectors. Likewise, we use a capital letter for psi and phi so we don’t confuse it with, for example, the lower-case φ (phi) representing the phase of a wave function.]

The position-space and momentum-space wave functions Ψ and Φ are related through the Uncertainty Principle. To be precise: they are Fourier transforms of each other. Huh? Don’t be put off by that statement. In fact, I shouldn’t have mentioned it, but then it’s how one can actually prove or derive the Uncertainty Principle from… Well… From ‘first principles’, let’s say, instead of just jotting it down as some God-given rule. Indeed, as Feynman puts: “The Uncertainty Principle should be seen in its historical context. If you get rid of all of the old-fashioned ideas and instead use the ideas that I’m explaining in these lectures—adding arrows for all the ways an event can happen—there is no need for an uncertainty principle!” However, I must assume you’re, just like me, not quite used to the new ideas as yet, and so let me just jot down the Uncertainty Principle once again, as some God-given rule indeed :-):

σx·σp ≥ ħ/2

This is the so-called Kennard formulation of the Principle: it measures the uncertainty about the exact position (x) as well as the momentum (p), in terms of the standard deviation (so that’s the σ (sigma) symbol) around the mean. To be precise, the assumption is that we cannot know the real x and p: we can only find some probability distribution for x and p, which is usually some nice “bell curve” in the textbooks. While the Kennard formulation is the most precise (and exact) formulation of the Uncertainty Principle (or uncertainty relation, I should say), you’ll often find ‘other’ formulations. These ‘other’ formulates usually write Δx and Δp instead of σx and σp, with the Δ symbol indicating some ‘spread’ or a similar concept—surely do not think of Δ as a differential or so! [Sorry for assuming you don’t know this (I know you do!) but I just want to make sure here!] Also, these ‘other’ formulations will usually (a) not mention the 1/2 factor, (b) substitute ħ for h (ħ = h/2π, as you know, so ħ is preferred when we’re talking things like angular frequency or other stuff involving the unit circle), or (c) put an equality (=) sign in, instead of an inequality sign (≥). Niels Bohr’s early formulation of the Uncertainty Principle actually does all of that:

ΔxΔp = h

So… Well… That’s a bit sloppy, isn’t it? Maybe. In Feynman’s Lectures, you’ll find an oft-quoted ‘application’ of the Uncertainty Principle leading to a pretty accurate calculation of the typical size of an atom (the so-called Bohr radius), which Feynman starts with an equally sloppy statement of the Uncertainty Principle, so he notes: “We needn’t trust our answer to within factors like 2, π etcetera.” Frankly, I used to think that’s ugly and, hence, doubt the ‘seriousness’ of such kind of calculations. Now I know it doesn’t really matter indeed, as the essence of the relationship is clearly not a 2, π or 2π factor. The essence is the uncertainty itself: it’s very tiny (and multiplying it with 2, π or 2π doesn’t make it much bigger) but so it’s there.

In this regard, I need to remind you of how tiny that physical constant ħ actually is: about 6.58×10−16 eV·s. So that’s a zero followed by a decimal point and fifteen zeroes: only then we get the first significant digits (65812…). And if 10−16 doesn’t look tiny enough for you, then just think about how tiny the electronvolt unit is: it’s the amount of (potential) energy gained (or lost) by an electron as it moves across a potential difference of one volt (which, believe me, is nothing much really): if we’d express ħ in Joule, then we’d have to add nineteen more zeroes, because 1 eV = 1.6×10−19 J. As for such phenomenally small numbers, I’ll just repeat what I’ve said many times before: we just cannot imagine such small number. Indeed, our mind can sort of intuitively deal with addition (and, hence, subtraction), and with multiplication and division (but to some extent only), but our mind is not made to understand non-linear stuff, such as exponentials indeed. If you don’t believe me, think of the Richter scale: can you explain the difference between a 4.0 and a 5.0 earthquake? […] If the answer to that question took you more than a second… Well… I am right. 🙂 [The Richter scale is based on the base-10 exponential function: a 5.0 earthquake has a shaking amplitude that is 10 times that of an earthquake that registered 4.0, and because energy is proportional to the square of the amplitude, that corresponds to an energy release that is 31.6 times that of the lesser earthquake.]

A digression on units

Having said what I said above, I am well aware of the fact that saying that we cannot imagine this or that is what most people say. I am also aware of the fact that they usually say that to avoid having to explain something. So let me try to do something more worthwhile here.

1. First, I should note that ħ is so small because the second, as a unit of time, is so incredibly large. All is relative, of course. 🙂 For sure, we should express time in a more natural unit at the atomic or sub-atomic scale, like the time that’s needed for light to travel one meter. Let’s do it. Let’s express time in a unit that I shall call a ‘meter‘. Of course, it’s not an actual meter (because it doesn’t measure any distance), but so I don’t want to invent a new word and surely not any new symbol here. Hence, I’ll just put apostrophes before and after: so I’ll write ‘meter’ or ‘m’. When adopting the ‘meter’ as a unit of time, we get a value for ‘ħ‘ that is equal to (6.6×10−16 eV·s)(1/3×108 ‘meter’/second) = 2.2×10−8 eV·’m’. Now, 2.2×10−8 is a number that is still too tiny to imagine. But then our ‘meter’ is still a rather huge unit at the atomic scale: we should take the ‘millimicron’, aka the ‘nanometer’ (1 nm = 1×10−9 m), or – even better because more appropriate – the ‘angstrom‘: 1 Å = 0.1 nm = 1×10−10 m. Indeed, the smallest atom (hydrogen) has a radius of 0.25 Å, while larger atoms will have a radius of about 1 or more Å. Now that should work, isn’t it? You’re right, we get a value for ‘ħ‘ equal to (6.6×10−16 eV·s)(1/3×108 ‘m’/s)(1×1010 ‘Å’/m) = 220 eV·’Å’, or 22 220 eV·’nm’. So… What? Well… If anything, it shows ħ is not a small unit at the atomic or sub-atomic level! Hence, we actually can start imagining how things work at the atomic level when using more adequate units.

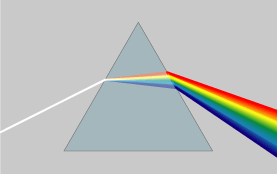

[Now, just to test your knowledge, let me ask you: what’s the wavelength of visible light in angstrom? […] Well? […] Let me tell you: 400 to 700 nm is 4000 to 7000 Å. In other words, the wavelength of visible light is quite sizable as compared to the size of atoms or electron orbits!]

2. Secondly, let’s do a quick dimension analysis of that ΔxΔp = h relation and/or its more accurate expression σx·σp ≥ ħ/2.

A position (and its uncertainty or standard deviation) is expressed in distance units, while momentum… Euh… Well… What? […] Momentum is mass times velocity, so it’s kg·m/s. Hence, the dimension of the product on the left-hand side of the inequality is m·kg·m/s = kg·m2/s. So what about this eV·s dimension on the right-hand side? Well… The electronvolt is a unit of energy, and so we can convert it to joules. Now, a joule is a newton-meter (N·m), which is the unit for both energy and work: it’s the work done when applying a force of one newton over a distance of one meter. So we now have N·m·s for ħ, which is nice, because Planck’s constant (h or ħ—whatever: the choice for one of the two depends on the variables we’re looking at) is the quantum for action indeed. It’s a Wirkung as they say in German, so its dimension combines both energy as well as time.

To put it simply, it’s a bit like power, which is what we men are interested in when looking at a car or motorbike engine. 🙂 Power is the energy spent or delivered per second, so its dimension is J/s, not J·s. However, your mind can see the similarity in thinking here. Energy is a nice concept, be it potential (think of a water bucket above your head) or kinetic (think of a punch in a bar fight), but it makes more sense to us when adding the dimension of time (emptying a bucket of water over your head is different than walking in the rain, and the impact of a punch depends on the power with which it is being delivered). In fact, the best way to understand the dimension of Planck’s constant is probably to also write the joule in ‘base units’. Again, one joule is the amount of energy we need to move an object over a distance of one meter against a force of one newton. So one J·s is one N·m·s is (1) a force of one newton acting over a distance of (2) one meter over a time period equal to (3) one second.

I hope that gives you a better idea of what ‘action’ really is in physics. […] In any case, we haven’t answered the question. How do we relate the two sides? Simple: a newton is an oft-used SI unit, but it’s not a SI base unit, and so we should deconstruct it even more (i.e. write it in SI base units). If we do that, we get 1 N = 1 kg·m/s2: one newton is the force needed to give a mass of 1 kg an acceleration of 1 m/s per second. So just substitute and you’ll see the dimension on the right-hand side is kg·(m/s2)·m·s = kg·m2/s, so it comes out alright.

Why this digression on units? Not sure. Perhaps just to remind you also that the Uncertainty Principle can also be expressed in terms of energy and time:

ΔE·Δt = h

Here there’s no confusion in regard to the units on both sides: we don’t need to convert to SI base units to see that they’re the same: [ΔE][Δt] = J·s.

The Uncertainty Principle revisited (2)

The ΔE·Δt = h expression is not so often used as an expression of the Uncertainty Principle. I am not sure why, and I don’t think it’s a good thing. Energy and time are also complementary variables in quantum mechanics, so it’s just like position and momentum indeed. In fact, I like the energy-time expression somewhat more than the position-momentum expression because it does not create any confusion in regard to the units on both sides: it’s just joules (or electronvolts) and seconds on both sides of the equation. So what?

Frankly, I don’t want to digress too much here (this post is going to become awfully long) but, personally, I found it hard, for quite a while, to relate the two expressions of the very same uncertainty ‘principle’ and, hence, let me show you how the two express the same thing really, especially because you may or may not know that there are even more pairs of complementary variables in quantum mechanics. So, I don’t know if the following will help you a lot, but it helped me to note that:

- The energy and momentum of a particle are intimately related through the (relativistic) energy-momentum relationship. Now, that formula, E2 = p2c2 – m02c4, which links energy, momentum and intrinsic mass (aka rest mass), looks quite monstrous at first. Hence, you may prefer a simpler form: pc = Ev/c. It’s the same really as both are based on the relativistic mass-energy equivalence: E = mc2 or, the way I prefer to write it: m = E/c2. [Both expressions are the same, obviously, but we can ‘read’ them differently: m = E/c2 expresses the idea that energy has a equivalent mass, defined as inertia, and so it makes energy the primordial concept, rather than mass.] Of course, you should note that m is the total mass of the object here, including both (a) its rest mass as well as (b) the equivalent mass it gets from moving at the speed v. So m, not m0, is the concept of mass used to define p, and note how easy it is to demonstrate the equivalence of both formulas: pc = Ev/c ⇔ mvc = Ev/c ⇔ E = mc2. In any case, the bottom line is: don’t think of the energy and momentum of a particle as two separate things; they are two aspects of the same ‘reality’, involving mass (a measure of inertia, as you know) and velocity (as measured in a particular (so-called inertial) reference frame).

- Time and space are intimately related through the universal constant c, i.e. the speed of light, as evidenced by the fact that we will often want to express distance not in meter but in light-seconds (i.e. the distance that light travels (in a vacuum) in one second) or, vice versa, express time in meter (i.e. the time that light needs to travel a distance of one meter).

These relationships are interconnected, and the following diagram shows how.

The easiest way to remember it all is to apply the Uncertainty Principle, in both its ΔE·Δt = h as well as its Δp·Δx = h expressions, to a photon. A photon has no rest mass and its velocity v is, obviously, c. So the energy-momentum relationship is a very simple one: p = E/c. We then get both expressions of the Uncertainty Principle by simply substituting E for p, or vice versa, and remember that time and position (or distance) are related in exactly the same way: the constant of proportionality is the very same. It’s c. So we can write: Δx = Δt·c and Δt = Δx/c. If you’re confused, think about it in very practical terms: because the speed of light is what it is, an uncertainty of a second in time amounts, roughly, to an uncertainty in position of some 300,000 km (c = 3×108 m/s). Conversely, an uncertainty of some 300,000 km in the position amounts to a uncertainty in time of one second. That’s what the 1-2-3 in the diagram above is all about: please check if you ‘get’ it, because that’s ‘essential’ indeed.

Back to ‘probability waves’

Matter-particles are not the same, but we do have the same relations, including that ‘energy-momentum duality’. The formulas are just somewhat more complicated because they involve mass and velocity (i.e. a velocity less than that of light). For matter-particles, we can see that energy-momentum duality not only in the relationships expressed above (notably the relativistic energy-momentum relation), but also in the (in)famous de Broglie relation, which associates some ‘frequency’ (f) to the energy (E) of a particle or, what amounts to the same, some ‘wavelength’ (λ) to its momentum (p):

λ = h/p and f = E/h

These two complementary equations give a ‘wavelength’ (λ) and/or a ‘frequency’ (f) of a de Broglie wave, or a ‘matter wave’ as it’s sometimes referred to. I am using, once again, apostrophes because the de Broglie wavelength and frequency are a different concept—different than the wavelength or frequency of light, or of any other ‘real’ wave (like water or sound waves, for example). To illustrate the differences, let’s start with a very simple question: what’s the velocity of a de Broglie wave? Well… […] So? You thought you knew, didn’t you?

Let me answer the question:

- The mathematically (and physically) correct answer involves distinguishing the group and phase velocity of a wave.

- The ‘easy’ answer is: the de Broglie wave of a particle moves with the particle and, hence, its velocity is, obviously, the speed of the particle which, for electrons, is usually non-relativistic (i.e. rather slow as compared to the speed of light).

To be clear on this, the velocity of a de Broglie wave is not the speed of light. So a de Broglie wave is not like an electromagnetic wave at all. They have nothing in common really, except for the fact that we refer to both of them as ‘waves’. 🙂

The second thing to note is that, when we’re talking about the ‘frequency’ or ‘wavelength’ of ‘matter waves’ (i.e. de Broglie waves), we’re talking the frequency and wavelength of a wave with two components: it’s a complex-valued wave function, indeed, and so we get a real and imaginary part when we’re ‘feeding’ the function with some values for x and t.

Thirdly and, perhaps, most importantly, we should always remember the Uncertainty Principle when looking at the de Broglie relation. The Uncertainty Principle implies that we can actually not assign any precise wavelength (or, what amounts to the same, a precise frequency) to a de Broglie wave: if there is a spread in p (and, hence, in E), then there will be a spread in λ (and in f). In fact, I tend to think that it would be better to write the de Broglie relation as an ‘uncertainty relation’ in its own right:

Δλ = Δ(h/p) = hΔp and Δf = ΔE/h = hΔE

Besides from underscoring the fact that we have other ‘pairs’ of complementary variables, this ‘version’ of the de Broglie equation would also remind us continually of the fact that a ‘regular’ wave with an exact frequency and/or an exact wavelength (so a Δλ and/or a Δf equal to zero) would not give us any information about the momentum and/or the energy. Indeed, as Δλ and/or Δf go to zero (Δλ → 0 and/or Δf → 0 ), then Δp and ΔE must go to infinity (Δp → ∞ and ΔE → ∞. That’s just the math involved in such expressions. 🙂

Jokes aside, I’ll admit I used to have a lot of trouble understanding this, so I’ll just quote the expert teacher (Feynman) on this to make sure you don’t get me wrong here:

“The amplitude to find a particle at a place can, in some circumstances, vary in space and time, let us say in one dimension, in this manner: Ψ = Aei(ωt−kx) , where ω is the frequency, which is related to the classical idea of the energy through E = ħω, and k is the wave number, which is related to the momentum through p = ħk. [These are equivalent formulations of the de Broglie relations using the angular frequency and the wave number instead of wavelength and frequency.] We would say the particle had a definite momentum p if the wave number were exactly k, that is, a perfect wave which goes on with the same amplitude everywhere. The Ψ = Aei(ωt−kx) equation [then] gives the [complex-valued probability] amplitude, and if we take the absolute square, we get the relative probability for finding the particle as a function of position and time. This is a constant, which means that the probability to find a [this] particle is the same anywhere.” (Feynman’s Lectures, I-48-5)

You may say or think: What’s the problem here really? Well… If the probability to find a particle is the same anywhere, then the particle can be anywhere and, for all practical purposes, that amounts to saying it’s nowhere really. Hence, that wave function doesn’t serve the purpose. In short, that nice Ψ = Aei(ωt−kx) function is completely useless in terms of representing an electron, or any other actual particle moving through space. So what to do?

The Wikipedia article on the Uncertainty Principle has this wonderful animation that shows how we can superimpose several waves, one on top of each other, to form a wave packet. Let me copy it below:

So that’s what the wave we want indeed: a wave packet that travels through space but which is, at the same time, limited in space. Of course, you should note, once again, that it shows only one part of the complex-valued probability amplitude: just visualize the other part (imaginary if the wave above would happen to represent the real part, and vice versa if the wave would happen to represent the imaginary part of the probability amplitude). The animation basically illustrates a mathematical operation. To be precise, it involves a Fourier analysis or decomposition: it separates a wave packet into a finite or (potentially) infinite number of component waves. Indeed, note how, in the illustration above, the frequency of the component waves gradually increases (or, what amounts to the same, how the wavelength gets smaller and smaller) and how, with every wave we ‘add’ to the packet, it becomes increasingly localized. Now, you can easily see that the ‘uncertainty’ or ‘spread’ in the wavelength here (which we’ll denote by Δλ) is, quite simply, the difference between the wavelength of the ‘one-cycle wave’, which is equal to the space the whole wave packet occupies (which we’ll denote by Δx), and the wavelength of the ‘highest-frequency wave’. For all practical purposes, they are about the same, so we can write: Δx ≈ Δλ. Using Bohr’s formulation of the Uncertainty Principle, we can see the expression I used above (Δλ = hΔp) makes sense: Δx = Δλ = h/Δp, so ΔλΔp = h.

[Just to be 100% clear on terminology: a Fourier decomposition is not the same as that Fourier transform I mentioned when talking about the relation between position and momentum in the Kennard formulation of the Uncertainty Principle, although these two mathematical concepts obviously have a few things in common.]

The wave train revisited

All what I’ve said above, is the ‘correct’ interpretation of the Uncertainty Principle and the de Broglie equation. To be frank, it took me quite a while to ‘get’ that—and, as you can see, it also took me quite a while to get ‘here’, of course. 🙂

In fact, I was confused, for quite a few years actually, because I never quite understood whey there had to be a spread in the wavelength of a wave train. Indeed, we can all easily imagine a localized wave train with a fixed frequency and a fixed wavelength, like the one below, which I’ll re-use later. I’ve made this wave train myself: it’s a standard sine and cosine function multiplied with an ‘envelope’ function generating the envelope. As you can see, it’s a complex-valued thing indeed: the blue curve is the real part, and the imaginary part is the red curve.

You can easily make a graph like this yourself. [Just use of one of those online graph tools.] This thing is localized in space and, as mentioned above, it has a fixed frequency and wavelength. So all those enigmatic statements you’ll find in serious or less serious books (i.e. textbooks or popular accounts) on quantum mechanics saying that “we cannot define a unique wavelength for a short wave train” and/or saying that “there is an indefiniteness in the wave number that is related to the finite length of the train, and thus there is an indefiniteness in the momentum” (I am quoting Feynman here, so not one of the lesser gods) are – with all due respect for these authors, especially Feynman – just wrong. I’ve made another ‘short wave train’ below, but this time it depicts the real part of a (possible) wave function only.

Hmm… Now that one has a weird shape, you’ll say. It doesn’t look like a ‘matter wave’! Well… You’re right. Perhaps. [I’ll challenge you in a moment.] The shape of the function above is consistent, though, with the view of a photon as a transient electromagnetic oscillation. Let me come straight to the point by stating the basics: the view of a photon in physics is that photons are emitted by atomic oscillators. As an electron jumps from one energy level to the other, it seems to oscillate back and forth until it’s in equilibrium again, thereby emitting an electromagnetic wave train that looks like a transient.

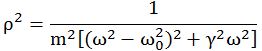

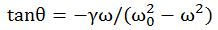

Huh? What’s a transient? It’s an oscillation like the one above: its amplitude and, hence, its energy, gets smaller and smaller as time goes by. To be precise, its energy level has the same shape as the envelope curve below: E = E0e–t/τ. In this expression, we have τ as the so-called decay time, and one can show it’s the inverse of the so-called decay rate: τ = 1/γ with γE = –dE/dt. In case you wonder, check it out on Wikipedia: it’s one of the many applications of the natural exponential function: we’re talking a so-called exponential decay here indeed, involves a quantity (in this case, the amplitude and/or the energy) decreasing at a rate that is proportional to its current value, with the coefficient of proportionality being γ. So we write that as γE = –dE/dt in mathematical notation. 🙂

I need to move on. All of what I wrote above was ‘plain physics’, but so what I really want to explore in this post is a crazy hypothesis. Could these wave trains above – I mean the wave trains with the fixed frequency and wavelength – possible represent a de Broglie wave for a photon?

You’ll say: of course not! But, let’s be honest, you’d have some trouble explaining why. The best answer you could probably come up with is: because no physics textbook says something like that. You’re right. It’s a crazy hypothesis because, when you ask a physicist (believe it or not, but I actually went through the trouble of asking two nuclear scientists), they’ll tell you that photons are not to be associated with de Broglie waves. [You’ll say: why didn’t you try looking for an answer on the Internet? I actually did but – unlike what I am used to – I got very confusing answers on this one, so I gave up trying to find some definite answer on this question on the Internet.]

However, these negative answers don’t discourage me from trying to do some more freewheeling. Before discussing whether or not the idea of a de Broglie wave for a photon makes sense, let’s think about mathematical constraints. I googled a bit but I only see one actually: the amplitudes of a de Broglie wave are subject to a normalization condition. Indeed, when everything is said and done, all probabilities must take a value between 0 and 1, and they must also all add up to exactly 1. So that’s a so-called normalization condition that obviously imposes some constraints on the (complex-valued) probability amplitudes of our wave function.

But let’s get back to the photon. Let me remind you of what happens when a photon is being emitted by inserting the two diagrams below, which gives the energy levels of the atomic orbitals of electrons.

So an electron absorbs or emits a photon when it goes from one energy level to the other, so it absorbs or emits radiation. And, of course, you will also remember that the frequency of the absorbed or emitted light is related to those energy levels. More specifically, the frequency of the light emitted in a transition from, let’s say, energy level E3 to E1 will be written as ν31 = (E3 – E1)/h. This frequency will be one of the so-called characteristic frequencies of the atom and will define a specific so-called spectral emission line.

Now, from a mathematical point of view, there’s no difference between that ν31 = (E3 – E1)/h equation and the de Broglie equation, f = E/h, which assigns a de Broglie wave to a particle. But, of course, from all that I wrote above, it’s obvious that, while these two formulas are the same from a math point of view, they represent very different things. Again, let me repeat what I said above: a de Broglie wave is a matter-wave and, as such, it has nothing to do with an electromagnetic wave.

Let me be even more explicit. A de Broglie wave is not a ‘real’ wave, in a sense (but, of course, that’s a very unscientific statement to make); it’s a psi function, so it represents these weird mathematical quantities–complex probability amplitudes–which allow us to calculate the probability of finding the particle at position x or, if it’s a wave function for the momentum-space, to find a value p for its momentum. In contrast, a photon that’s emitted or absorbed represents a ‘real’ disturbance of the electromagnetic field propagating through space. Hence, that frequency ν is something very different than f, which is why we use another symbol for it (ν is the Greek letter nu, not to be confused with the v symbol we use for velocity). [Of course, you may wonder how ‘real’ or ‘unreal’ an electromagnetic field is but, in the context of this discussion, let me assure you we should look at it as something that’s very real.]

That being said, we also know light is emitted in discrete energy packets: in fact, that’s how photons were defined originally, first by Planck and then by Einstein. Now, when an electron falls from one energy level in an atom to another (lower) energy level, it emits one – and only one – photon with that particular wavelength and energy. The question then is: how should we picture that photon? Does it also have some more or less defined position in space, and some momentum? The answer is definitely yes, on both accounts:

- Subject to the constraints of the Uncertainty Principle, we know, more or less indeed, when a photon leaves a source and when it hits some detector. [And, yes, due to the ‘Uncertainty Principle’ or, as Feynman puts it, the rules for adding arrows, it may not travel in a straight line and/or at the speed of light—but that’s a discussion that, believe it or not, is not directly relevant here. If you want to know more about it, check one or more of my posts on it.]

- We also know light has a very definite momentum, which I’ve calculated elsewhere and so I’ll just note the result: p = E/c. It’s a ‘pushing momentum’ referred to as radiation pressure, and its in the direction of travel indeed.

In short, it does makes sense, in my humble opinion that is, to associate some wave function with the photon, and then I mean a de Broglie wave. Just think about it yourself. You’re right to say that a de Broglie wave is a ‘matter wave’, and photons aren’t matter but, having said that, photons do behave like like electrons, don’t they? There’s diffraction (when you send a photon through one slit) and interference (when photons go through two slits, altogether or – amazingly – one by one), so it’s the same weirdness as electrons indeed, and so why wouldn’t we associate some kind of wave function with them?

You can react in one of three ways here. The first reaction is: “Well… I don’t know. You tell me.” Well… That’s what I am trying to do here. 🙂

The second reaction may be somewhat more to the point. For example, those who’ve read Feynman’s Strange Theory of Light and Matter, could say: “Of course, why not? That’s what we do when we associate a photon going from point A to B with an amplitude P(A to B), isn’t it?”

Well… No. I am talking about something else here. Not some amplitude associated with a path in spacetime, but a wave function giving an approximate position of the photon.

The third reaction may be the same as the reaction of those two nuclear scientists I asked: “No. It doesn’t make sense. We do not associate photons with a de Broglie wave.” But so they didn’t tell me why because… Well… They didn’t have the time to entertain a guy like me and so I didn’t dare to push the question and continued to explore it more in detail myself.

So I’ve done that, and I thought of one reason why the question, perhaps, may not make all that much sense: a photon travels at the speed of light; therefore, it has no length. Hence, doing what I am doing below, and that’s to associate the electromagnetic transient with a de Broglie wave might not make sense.

Maybe. I’ll let you judge. Before developing the point, I’ll raise two objections to the ‘objection’ raised above (i.e. the statement that a photon has no length). First, if we’re looking at the photon as some particle, it will obviously have no length. However, an electromagnetic transient is just what it is: an electromagnetic transient. I’ve see nothing that makes me think its length should be zero. In fact, if that would be the case, the concept of an electromagnetic wave itself would not make sense, as its ‘length’ would always be zero. Second, even if – somehow – the length of the electromagnetic transient would be reduced to zero because of its speed, we can still imagine that we’re looking at the emission of an electromagnetic pulse (i.e. a photon) using the reference frame of the photon, so that we’re traveling at speed c,’ riding’ with the photon, so to say, as it’s being emitted. Then we would ‘see’ the electromagnetic transient as it’s being radiated into space, wouldn’t we?

Perhaps. I actually don’t know. That’s why I wrote this post and hope someone will react to it. I really don’t know, so I thought it would be nice to just freewheel a bit on this question. So be warned: nothing of what I write below has been researched really, so critical comments and corrections from actual specialists are more than welcome.

The shape of a photon wave

As mentioned above, the answer in regard to the definition of a photon’s position and momentum is, obviously, unambiguous. Perhaps we have to stretch whatever we understand of Einstein’s (special) relativity theory, but we should be able to draw some conclusions, I feel.

Let me say one thing more about the momentum here. As said, I’ll refer you to one of my posts for the detail but, all you should know here is that the momentum of light is related to the magnetic field vector, which we usually never mention when discussing light because it’s so tiny as compared to the electric field vector in our inertial frame of reference. Indeed, the magnitude of the magnetic field vector is equal to the magnitude of the electric field vector divided by c = 3×108, so we write B = E/c. Now, the E here stands for the electric field, so let me use W to refer to the energy instead of E. Using the B = E/c equation and a fairly straightforward calculation of the work that can be done by the associated force on a charge that’s being put into this field, we get that famous equation which we mentioned above already: the momentum of a photon is its total energy divided by c, so we write p = W/c. You’ll say: so what? Well… Nothing. I just wanted to note we get the same p = W/c equation indeed, but from a very different angle of analysis here. We didn’t use the energy-momentum relation here at all! In any case, the point to note is that the momentum of a photon is only a tiny fraction of its energy (p = W/c), and that the associated magnetic field vector is also just a tiny fraction of the electric field vector (B = E/c).

But so it’s there and, in fact, when adopting a moving reference frame, the mix of E and B (i.e. the electric and magnetic field) becomes an entirely different one. One of the ‘gems’ in Feynman’s Lectures is the exposé on the relativity of electric and magnetic fields indeed, in which he analyzes the electric and magnetic field caused by a current, and in which he shows that, if we switch our inertial reference frame for that of the moving electrons in the wire, the ‘magnetic’ field disappears, and the whole electromagnetic effect becomes ‘electric’ indeed.

I am just noting this because I know I should do a similar analysis for the E and B ‘mixture’ involved in the electromagnetic transient that’s being emitted by our atomic oscillator. However, I’ll admit I am not quite comfortably enough with the physics nor the math involved to do that, so… Well… Please do bear this in mind as I will be jotting down some quite speculative thoughts in what follows.

So… A photon is, in essence, a electromagnetic disturbance and so, when trying to picture a photon, we can think of some oscillating electric field vector traveling through–and also limited in–space. [Note that I am leaving the magnetic field vector out of the analysis from the start, which is not ‘nice’ but, in light of that B = E/c relationship, I’ll assume it’s acceptable.] In short, in the classical world – and in the classical world only of course – a photon must be some electromagnetic wave train, like the one below–perhaps.

But why would it have that shape? I only suggested it because it has the same shape as Feynman’s representation of a particle (see below) as a ‘probability wave’ traveling through–and limited in–space.

So, what about it? Let me first remind you once again (I just can’t stress this point enough it seems) that Feynman’s representation – and most are based on his, it seems – is misleading because it suggests that ψ(x) is some real number. It’s not. In the image above, the vertical axis should not represent some real number (and it surely should not represent a probability, i.e. some real positive number between 0 and 1) but a probability amplitude, i.e. a complex number in which both the real and imaginary part are important. Just to be fully complete (in case you forgot), such complex-valued wave function ψ(x) will give you all the probabilities you need when you take its (absolute) square, but so… Well… We’re really talking a different animal here, and the image above gives you only one part of the complex-valued wave function (either the real or the imaginary part), while it should give you both. That’s why I find my graph below much better. 🙂 It’s the same really, but so it shows both the real as well as the complex part of a wave function.

But let me go back to the first illustration: the vertical axis of the first illustration is not ψ but E – the electric field vector. So there’s no imaginary part here: just a real number, representing the strength–or magnitude I should say– of the electric field E as a function of the space coordinate x. [Can magnitudes be negative? The honest answer is: no, they can’t. But just think of it as representing the field vector pointing in the other way .]

Regardless of the shortcomings of this graph, including the fact we only have some real-valued oscillation here, would it work as a ‘suggestion’ of how a real-life photon could look like?

Of course, you could try to not answer that question by mumbling something like: “Well… It surely doesn’t represent anything coming near to a photon in quantum mechanics.” But… Well… That’s not my question here: I am asking you to be creative and ‘think outside of the box’, so to say. 🙂

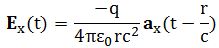

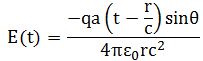

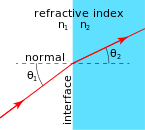

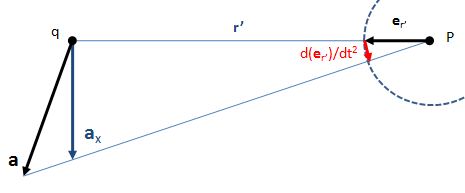

So you should say ‘No!’ because of some other reason. What reason? Well… If a photon is an electromagnetic transient – in other words, if we adopt a purely classical point of view – it’s going to be a transient wave indeed, and so then it should walk, talk and even look like a transient. 🙂 Let me quickly jot down the formula for the (vertical) component of E as a function of the acceleration of some charge q:

The charge q (i.e. the source of the radiation) is, of course, our electron that’s emitting the photon as it jumps from a higher to a lower energy level (or, vice versa, absorbing it). This formula basically states that the magnitude of the electric field (E) is proportional to the acceleration (a) of the charge (with t–r/c the retarded argument). Hence, the suggested shape of E as a function of x as shown above would imply that the acceleration of the electron is (a) initially quite small, (b) then becomes larger and larger to reach some maximum, and then (c) becomes smaller and smaller again to then die down completely. In short, it does match the definition of a transient wave sensu stricto (Wikipedia defines a transient as “a short-lived burst of energy in a system caused by a sudden change of state”) but it’s not likely to represent any real transient. So, we can’t exclude it, but a real transient is much more likely to look like something what’s depicted below: no gradual increase in amplitude but big swings initially which then dampen to zero. In other words, if our photon is a transient electromagnetic disturbance caused by a ‘sudden burst of energy’ (which is what that electron jump is, I would think), then its representation will, much more likely, resemble a damped wave, like the one below, rather than Feynman’s picture of a moving matter-particle.

In fact, we’d have to flip the image, both vertically and horizontally, because the acceleration of the source and the field are related as shown below. The vertical flip is because of the minus sign in the formula for E(t). The horizontal flip is because of the minus sign in the (t – r/c) term, the retarded argument: if we add a little time (Δt), we get the same value for a(t−r/c) as we would have if we had subtracted a little distance: Δr=−cΔt. So that’s why E as a function of r (or of x), i.e. as a function in space, is a ‘reversed’ plot of the acceleration as a function of time.

So we’d have something like below.

What does this resemble? It’s not a vibrating string (although I do start to understand the attractiveness of string theory now: vibrating strings are great as energy storage systems, so the idea of a photon being some kind of vibrating string sounds great, doesn’t it?). It’s not resembling a bullwhip effect either, because the oscillation of a whip is confined by a different envelope (see below). And, no, it’s also definitely not a trumpet. 🙂

It’s just what it is: an electromagnetic transient traveling through space. Would this be realistic as a ‘picture’ of a photon? Frankly, I don’t know. I’ve looked at a lot of stuff but didn’t find anything on this really. The easy answer, of course, is quite straightforward: we’re not interested in the shape of a photon because we know it is not an electromagnetic wave. It’s a ‘wavicle’, just like an electron.

[…] Sure. I know that too. Feynman told me. 🙂 But then why wouldn’t we associate some wave function with it? Please tell me, because I really can’t find much of an answer to that question in the literature, and so that’s why I am freewheeling here. So just go along with me for a while, and come up with another suggestion. As I said above, your bet is as good as mine. All that I know is that there’s one thing we need to explain when considering the various possibilities: a photon has a very well-defined frequency (which defines its color in the visible light spectrum) and so our wave train should – in my humble opinion – also have that frequency. At least for ‘quite a while’—and then I mean ‘most of the time’, or ‘on average’ at least. Otherwise the concept of a frequency – or a wavelength – wouldn’t make much sense. Indeed, if the photon has no defined wavelength or frequency, then we could not perceive it as some color (as you may or may not know, the sense of ‘color’ is produced by our eye and brain, but so it’s definitely associated with the frequency of the light). A photon should have a color (in phyics, that means a frequency) because, when everything is said and done, that’s what the Planck relation is all about.

What would be your alternative? I mean… Doesn’t it make sense to think that, when jumping from one energy level to the other, the electron would initially sort of overshoot its new equilibrium position, to then overshoot it again on the other side, and so on and so on, but with an amplitude that becomes smaller and smaller as the oscillation dies out? In short, if we look at radiation as being caused by atomic oscillators, why would we not go all the way and think of them as oscillators subject to some damping force? Just think about it. 🙂

The size of a photon wave

Let’s forget about the shape for a while and think about size. We’ve got an electromagnetic train here. So how long would it be? Well… Feynman calculated the Q of these atomic oscillators: it’s of the order of 108 (see his Lectures, I-33-3: it’s a wonderfully simple exercise, and one that really shows his greatness as a physics teacher) and, hence, this wave train will last about 10–8 seconds (that’s the time it takes for the radiation to die out by a factor 1/e). To give a somewhat more precise example, for sodium light, which has a frequency of 500 THz (500×1012 oscillations per second) and a wavelength of 600 nm (600×10–9 meter), the radiation will lasts about 3.2×10–8 seconds. [In fact, that’s the time it takes for the radiation’s energy to die out by a factor 1/e, so(i.e. the so-called decay time τ), so the wavetrain will actually last longer, but so the amplitude becomes quite small after that time.]

So that’s a very short time, but still, taking into account the rather spectacular frequency (500 THz) of sodium light, that still makes for some 16 million oscillations and, taking into the account the rather spectacular speed of light (3×108 m/s), that makes for a wave train with a length of, roughly, 9.6 meter. Huh? 9.6 meter!?

You’re right. That’s an incredible distance: it’s like infinity on an atomic scale!

So… Well… What to say? Such length surely cannot match the picture of a photon as a fundamental particle which cannot be broken up, can it? So it surely cannot be right because, if this would be the case, then there surely must be some way to break this thing up and, hence, it cannot be ‘elementary’, can it?

Well… Maybe. But think it through. First note that we will not see the photon as a 10-meter long string because it travels at the speed of light indeed and so the length contraction effect ensure its length, as measured in our reference frame (and from whatever ‘real-life’ reference frame actually, because the speed of light will always be c, regardless of the speeds we mortals could ever reach (including speeds close to c), is zero.

So, yes, I surely must be joking here but, as far as jokes go, I can’t help thinking this one is fairly robust from a scientific point of view. Again, please do double-check and correct me, but all what I’ve written so far is not all that speculative. It corresponds to all what I’ve read about it: only one photon is produced per electron in any de-excitation, and its energy is determined by the number of energy levels it drops, as illustrated (for a simple hydrogen atom) below. For those who continue to be skeptical about my sanity here, I’ll quote Feynman once again:

“What happens in a light source is that first one atom radiates, then another atom radiates, and so forth, and we have just seen that atoms radiate a train of waves only for about 10–8 sec; after 10–8 sec, some atom has probably taken over, then another atom takes over, and so on. So the phases can really only stay the same for about 10–8 sec. Therefore, if we average for very much more than 10–8 sec, we do not see an interference from two different sources, because they cannot hold their phases steady for longer than 10–8 sec. With photocells, very high-speed detection is possible, and one can show that there is an interference which varies with time, up and down, in about 10–8 sec.” (Feynman’s Lectures, I-34-4)

So… Well… Now it’s up to you. I am going along here with the assumption that a photon in the visible light spectrum, from a classical world perspective, should indeed be something that’s several meters long and packs a few million oscillations. So, while we usually measure stuff in seconds, or hours, or years, and, hence, while we would that think 10–8 seconds is short, a photon would actually be a very stretched-out transient that occupies quite a lot of space. I should also add that, in light of that number of ten meter, the dampening seems to happen rather slowly!

[…]

I can see you shaking your head now, for various reasons.

First because this type of analysis is not appropriate. […] You think so? Well… I don’t know. Perhaps you’re right. Perhaps we shouldn’t try to think of a photon as being something different than a discrete packet of energy. But then we also know it is an electromagnetic wave. So why wouldn’t we go all the way?

Second, I guess you may find the math involved in this post not to your liking, even if it’s quite simple and I am not doing anything spectacular here. […] Well… Frankly, I don’t care. Let me bulldozer on. 🙂

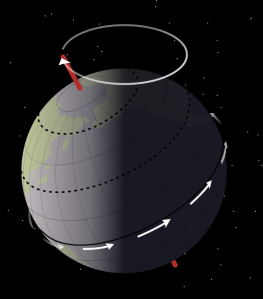

What about the ‘vertical’ dimension, the y and the z coordinates in space? We’ve got this long snaky thing: how thick-bodied is it?

Here, we need to watch our language. While it’s fairly obvious to associate a wave with a cross-section that’s normal to its direction of propagation, it is not obvious to associate a photon with the same thing. Not at all actually: as that electric field vector E oscillates up and down (or goes round and round, as shown in the illustration below, which is an image of a circularly polarized wave), it does not actually take any space. Indeed, the electric and magnetic field vectors E and B have a direction and a magnitude in space but they’re not representing something that is actually taking up some small or larger core in space.

Hence, the vertical axis of that graph showing the wave train does not indicate some spatial position: it’s not a y-coordinate but the magnitude of an electric field vector. [Just to underline the fact that the magnitude E has nothing to do with spatial coordinates: note that its value depends on the unit we use to measure field strength (so that’s newton/coulomb, if you want to know), so it’s really got nothing to do with an actual position in space-time.]

So, what can we say about it? Nothing much, perhaps. But let me try.

Cross-sections in nuclear physics

In nuclear physics, the term ‘cross-section’ would usually refer to the so-called Thompson scattering cross-section of an electron (or any charged particle really), which can be defined rather loosely as the target area for the incident wave (i.e. the photons): it is, in fact, a surface which can be calculated from what is referred to as the classical electron radius, which is about 2.82×10–15 m. Just to compare: you may or may not remember the so-called Bohr radius of an atom, which is about 5.29×10–11 m, so that’s a length that’s about 20,000 times longer. To be fully complete, let me give you the exact value for the Thompson scattering cross-section of an electron: 6.62×10–29 m2 (note that this is a surface indeed, so we have m squared as a unit, not m).

Now, let me remind you – once again – that we should not associate the oscillation of the electric field vector with something actually happening in space: an electromagnetic field does not move in a medium and, hence, it’s not like a water or sound wave, which makes molecules go up and down as it propagates through its medium. To put it simply: there’s nothing that’s wriggling in space as that photon is flashing through space. However, when it does hit an electron, that electron will effectively ‘move’ (or vibrate or wriggle or whatever you can imagine) as a result of the incident electromagnetic field.

That’s what’s depicted and labeled below: there is a so-called ‘radial component’ of the electric field, and I would say: that’s our photon! [What else would it be?] The illustration below shows that this ‘radial’ component is just E for the incident beam and that, for the scattered beam, it is, in fact, determined by the electron motion caused by the incident beam through that relation described above, in which a is the normal component (i.e. normal to the direction of propagation of the outgoing beam) of the electron’s acceleration.

Now, before I proceed, let me remind you once again that the above illustration is, once again, one of those illustrations that only wants to convey an idea, and so we should not attach too much importance to it: the world at the smallest scale is best not represented by a billiard ball model. In addition, I should also note that the illustration above was taken from the Wikipedia article on elastic scattering (i.e. Thomson scattering), which is only a special case of the more general Compton scattering that actually takes place. It is, in fact, the low-energy limit. Photons with higher energy will usually be absorbed, and then there will be a re-emission, but, in the process, there will be a loss of energy in this ‘collision’ and, hence, the scattered light will have lower energy (and, hence, lower frequency and longer wavelength). But – Hey! – now that I think of it: that’s quite compatible with my idea of damping, isn’t it? 🙂 [If you think I’ve gone crazy, I am really joking here: when it’s Compton scattering, there’s no ‘lost’ energy: the electron will recoil and, hence, its momentum will increase. That’s what’s shown below (credit goes to the HyperPhysics site).]

So… Well… Perhaps we should just assume that a photon is a long wave train indeed (as mentioned above, ten meter is very long indeed: not an atomic scale at all!) but that its effective ‘radius’ should be of the same order as the classical electron radius. So what’s that order? If it’s more or less the same radius, then it would be in the order of femtometers (1 fm = 1 fermi = 1×10–15 m). That’s good because that’s a typical length-scale in nuclear physics. For example, it would be comparable with the radius of a proton. So we look at a photon here as something very different – because it’s so incredibly long (at least as measured from its own reference frame) – but as something which does have some kind of ‘radius’ that is normal to its direction of propagation and equal or smaller than the classical electron radius. [Now that I think of it, we should probably think of it as being substantially smaller. Why? Well… An electron is obviously fairly massive as compared to a photon (if only because an electron has a rest mass and a photon hasn’t) and so… Well… When everything is said and done, it’s the electron that absorbs a photon–not the other way around!]

Now, that radius determines the area in which it may produce some effect, like hitting an electron, for example, or like being detected in a photon detector, which is just what this so-called radius of an atom or an electron is all about: the area which is susceptible of being hit by some particle (including a photon), or which is likely to emit some particle (including a photon). What is exactly, we don’t know: it’s still as spooky as an electron and, therefore, it also does not make all that much sense to talk about its exact position in space. However, if we’d talk about its position, then we should obviously also invoke the Uncertainty Principle, which will give us some upper and lower bounds for its actual position, just like it does for any other particle: the uncertainty about its position will be related to the uncertainty about its momentum, and more knowledge about the former, will implies less knowledge about the latter, and vice versa. Therefore, we can also associate some complex wave function with this photon which is – for all practical purposes – a de Broglie wave. Now how should we visualize that wave?

Well… I don’t know. I am actually not going to offer anything specific here. First, it’s all speculation. Second, I think I’ve written too much rubbish already. However, if you’re still reading, and you like this kind of unorthodox application of electromagnetics, then the following remarks may stimulate your imagination.

The first thing to note is that we should not end up with a wave function that, when squared, gives us a constant probability for each and every point in space. No. The wave function needs to be confined in space and, hence, we’re also talking a wave train here, and a very short one in this case. So… Well… What about linking its amplitude to the amplitude of the field for the photon. In other words, the probability amplitude could, perhaps, be proportional to the amplitude of E, with the proportionality factor being determined by (a) the unit in which we measure E (i.e. newton/coulomb) and (b) the normalization condition.

OK. I hear you say it now: “Ha-ha! Got you! Now you’re really talking nonsense! How can a complex number (the probability amplitude) be proportional to some real number (the field strength)?”

Well… Be creative. It’s not that difficult to imagine some linkages. First, the electric field vector has both a magnitude and a direction. Hence, there’s more to E than just its magnitude. Second, you should note that the real and imaginary part of a complex-valued wave function is a simple sine and cosine function, and so these two functions are the same really, except for a phase difference of π/2. In other words, if we have a formula for the real part of a wave function, we have a formula for its imaginary part as well. So… Your remark is to the point and then it isn’t.

OK, you’ll say, but then so how exactly would you link the E vector with the ψ(x, t) function for a photon. Well… Frankly, I am a bit exhausted now and so I’ll leave any further speculation to you. The whole idea of a de Broglie wave of a photon, with the (complex-valued) amplitude having some kind of ‘proportional’ relationship to the (magnitude of) the electric field vector makes sense to me, although we’d have to be innovative about what that ‘proportionality’ exactly is.

Let me conclude this speculative business by noting a few more things about our ‘transient’ electromagnetic wave:

1. First, it’s obvious that the usual relations between (a) energy (W), (b) frequency (f) and (c) amplitude (A) hold. If we increase the frequency of a wave, we’ll have a proportional increase in energy (twice the frequency is twice the energy), with the factor of proportionality being given by the Planck-Einstein relation: W = hf. But if we’re talking amplitudes (for which we do not have a formula, which is why we’re engaging in those assumptions on the shape of the transient wave), we should not forget that the energy of a wave is proportional to the square of its amplitude: W ∼ A2. Hence, a linear increase of the amplitudes results in an exponential (quadratic) increase in energy (e.g. if you double all amplitudes, you’ll pack four times more energy in that wave).

2. Both factors come into play when an electron emits a photon. Indeed, if the difference between the two energy levels is larger, then the photon will not only have a higher frequency (i.e. we’re talking light (or electromagnetic radiation) in the upper ranges of the spectrum then) but one should also expect that the initial overshooting – and, hence, the initial oscillation – will also be larger. In short, we’ll have larger amplitudes. Hence, higher-energy photons will pack even more energy upfront. They will also have higher frequency, because of the Planck relation. So, yes, both factors would come into play.

What about the length of these wave trains? Would it make them shorter? Yes. I’ll refer you to Feynman’s Lectures to verify that the wavelength appears in the numerator of the formula for Q. Hence, higher frequency means shorter wavelength and, hence, lower Q. Now, I am not quite sure (I am not sure about anything I am writing here it seems) but this may or may not be the reason for yet another statement I never quite understood: photons with higher and higher energy are said to become smaller and smaller, and when they reach the Planck scale, they are said to become black holes.

Hmm… I should check on that. 🙂

Conclusion

So what’s the conclusion? Well… I’ll leave it to you to think about this. As said, I am a bit tired now and so I’ll just wrap this up, as this post has become way too long anyway. Let me, before parting, offer the following bold suggestion in terms of finding a de Broglie wave for our photon: perhaps that transient above actually is the wave function.

You’ll say: What !? What about normalization? All probabilities have to add up to one and, surely, those magnitudes of the electric field vector wouldn’t add up to one, would they?

My answer to that is simple: that’s just a question of units, i.e. of normalization indeed. So just measure the field strength in some other unit and it will come all right.

[…] But… Yes? What? Well… Those magnitudes are real numbers, not complex numbers.

I am not sure how to answer that one but there’s two things I could say:

- Real numbers are complex numbers too: it’s just that their imaginary part is zero.

- When working with waves, and especially with transients, we’ve always represented them using the complex exponential function. For example, we would write a wave function whose amplitude varies sinusoidally in space and time as Aei(ωt−k·r), with ω the (angular) frequency and k the wave number (so that’s the wavelength expressed in radians per unit distance).

So, frankly, think about it: where is the photon? It’s that ten-meter long transient, isn’t it? And the probability to find it somewhere is the (absolute) square of some complex number, right? And then we have a wave function already, representing an electromagnetic wave, for which we know that the energy which it packs is the square of its amplitude, as well as being proportional to its frequency. We also know we’re more likely to detect something with high energy than something with low energy, don’t we? So… Tell me why the transient itself would not make for a good psi function?

But then what about these probability amplitudes being a function of the y and z coordinates?

Well… Frankly, I’ve started to wonder if a photon actually has a radius. If it doesn’t have a mass, it’s probably the only real point-like particle (i.e. a particle not occupying any space) – as opposed to all other matter-particles, which do have mass.

Why?

I don’t know. Your guess is as good as mine. Maybe our concepts of amplitude and frequency of a photon are not very relevant. Perhaps it’s only energy that counts. We know that a photon has a more or less well-defined energy level (within the limits of the Uncertainty Principle) and, hence, our ideas about how that energy actually gets distributed over the frequency, the amplitude and the length of that ‘transient’ have no relation with reality. Perhaps we like to think of a photon as a transient electromagnetic wave, because we’re used to thinking in terms of waves and fields, but perhaps a photon is just a point-like thing indeed, with a wave function that’s got the same shape as that transient. 🙂

Post scriptum: Perhaps I should apologize to you, my dear reader. It’s obvious that, in quantum mechanics, we don’t think of a photon as having some frequency and some wavelength and some dimension in space: it’s just an elementary particle with energy interacting with other elementary particles with energy, and we use these coupling constants and what have you to work with them. So we don’t usually think of photons as ten-meter long transients moving through space. So, when I write that “our concepts of amplitude and frequency of a photon are maybe not very relevant” when trying to picture a photon, and that “perhaps, it’s only energy that counts”, I actually don’t mean “maybe” or “perhaps“. I mean: Of course! […] In the quantum-mechanical world view, that is.

So I apologize for, perhaps, posting what may or may not amount to plain nonsense. However, as all of this nonsense helps me to make sense of these things myself, I’ll just continue. 🙂 I seem to move very slowly on this Road to Reality, but the good thing about moving slowly, is that it will − hopefully − give me the kind of ‘deeper’ understanding I want, i.e. an understanding beyond the formulas and mathematical and physical models. In the end, that’s all that I am striving for when pursuing this ‘hobby’ of mine. Nothing more, nothing less. 🙂 Onwards!

Some content on this page was disabled on June 17, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from Michael A. Gottlieb, Rudolf Pfeiffer, and The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here:

https://wordpress.com/support/copyright-and-the-dmca/

Some content on this page was disabled on June 17, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from Michael A. Gottlieb, Rudolf Pfeiffer, and The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here:

https://wordpress.com/support/copyright-and-the-dmca/

Some content on this page was disabled on June 20, 2020 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from Michael A. Gottlieb, Rudolf Pfeiffer, and The California Institute of Technology. You can learn more about the DMCA here:

https://wordpress.com/support/copyright-and-the-dmca/

, is the collection of these peaks at the frequencies that appear in this resolution of the function.”

, is the collection of these peaks at the frequencies that appear in this resolution of the function.”