Pre-script (dated 26 June 2020): Our ideas have evolved into a full-blown realistic (or classical) interpretation of all things quantum-mechanical. So no use to read this. Read my recent papers instead. 🙂

Original post:

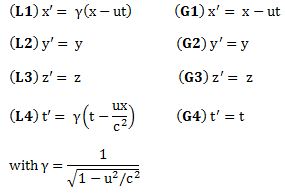

You know the two de Broglie relations, also known as matter-wave equations:

f = E/h and λ = h/p

You’ll find them in almost any popular account of quantum mechanics, and the writers of those popular books will tell you that f is the frequency of the ‘matter-wave’, and λ is its wavelength. In fact, to add some more weight to their narrative, they’ll usually write them in a somewhat more sophisticated form: they’ll write them using ω and k. The omega symbol (using a Greek letter always makes a big impression, doesn’t it?) denotes the angular frequency, while k is the so-called wavenumber. Now, k = 2π/λ and ω = 2π·f and, therefore, using the definition of the reduced Planck constant, i.e. ħ = h/2π, they’ll write the same relations as:

- λ = h/p = 2π/k ⇔ k = 2π·p/h

- f = E/h = (ω/2π)

⇒ k = p/ħ and ω = E/ħ

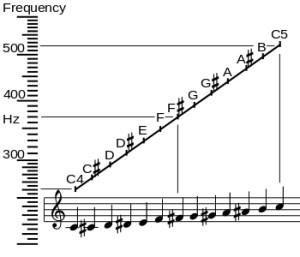

They’re the same thing: it’s just that working with angular frequencies and wavenumbers is more convenient, from a mathematical point of view that is: it’s why we prefer expressing angles in radians rather than in degrees (k is expressed in radians per meter, while ω is expressed in radians per second). In any case, the ‘matter wave’ – even Wikipedia uses that term now – is, of course, the amplitude, i.e. the wave-function ψ(x, t), which has a frequency and a wavelength, indeed. In fact, as I’ll show in a moment, it’s got two frequencies: one temporal, and one spatial. I am modest and, hence, I’ll admit it took me quite a while to fully distinguish the two frequencies, and so that’s why I always had trouble connecting these two ‘matter wave’ equations.

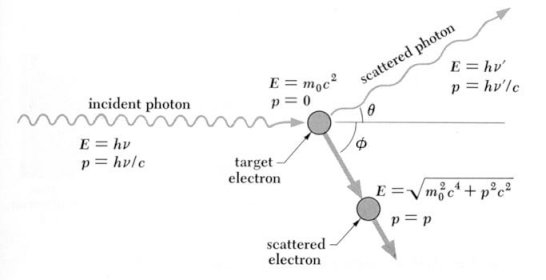

Indeed, if they represent the same thing, they must be related, right? But how exactly? It should be easy enough. The wavelength and the frequency must be related through the wave velocity, so we can write: f·λ = v, with v the velocity of the wave, which must be equal to the classical particle velocity, right? And then momentum and energy are also related. To be precise, we have the relativistic energy-momentum relationship: p·c = mv·v·c = mv·c2·v/c = E·v/c. So it’s just a matter of substitution. We should be able to go from one equation to the other, and vice versa. Right?

Well… No. It’s not that simple. We can start with either of the two equations but it doesn’t work. Try it. Whatever substitution you try, there’s no way you can derive one of the two equations above from the other. The fact that it’s impossible is evidenced by what we get when we’d multiply both equations. We get:

- f·λ = (E/h)·(h/p) = E/p

- v = f·λ ⇒ f·λ = v = E/p ⇔ E = v·p = v·(m·v)

⇒ E = m·v2

Huh? What kind of formula is that? E = m·v2? That’s a formula you’ve never ever seen, have you? It reminds you of the kinetic energy formula of course—K.E. = m·v2/2—but… That factor 1/2 should not be there. Let’s think about it for a while. First note that this E = m·v2 relation makes perfectly sense if v = c. In that case, we get Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence (E = m·c2), but that’s besides the point here. The point is: if v = c, then our ‘particle’ is a photon, really, and then the E = h·f is referred to as the Planck-Einstein relation. The wave velocity is then equal to c and, therefore, f·λ = c, and so we can effectively substitute to find what we’re looking for:

E/p = (h·f)/(h/λ) = f·λ = c ⇒ E = p·c

So that’s fine: we just showed that the de Broglie relations are correct for photons. [You remember that E = p·c relation, no? If not, check out my post on it.] However, while that’s all nice, it is not what the de Broglie equations are about: we’re talking the matter-wave here, and so we want to do something more than just re-confirm that Planck-Einstein relation, which you can interpret as the limit of the de Broglie relations for v = c. In short, we’re doing something wrong here! Of course, we are. I’ll tell you what exactly in a moment: it’s got to do with the fact we’ve got two frequencies really.

Let’s first try something else. We’ve been using the relativistic E = mv·c2 equation above. Let’s try some other energy concept: let’s substitute the E in the f = E/h by the kinetic energy and then see where we get—if anywhere at all. So we’ll use the Ekinetic = m∙v2/2 equation. We can then use the definition of momentum (p = m∙v) to write E = p2/(2m), and then we can relate the frequency f to the wavelength λ using the v = λ∙f formula once again. That should work, no? Let’s do it. We write:

- E = p2/(2m)

- E = h∙f = h·v/λ

⇒ λ = h·v/E = h·v/(p2/(2m)) = h·v/[m2·v2/(2m)] = h/[m·v/2] = 2∙h/p

So we find λ = 2∙h/p. That is almost right, but not quite: that factor 2 should not be there. Well… Of course you’re smart enough to see it’s just that factor 1/2 popping up once more—but as a reciprocal, this time around. 🙂 So what’s going on? The honest answer is: you can try anything but it will never work, because the f = E/h and λ = h/p equations cannot be related—or at least not so easily. The substitutions above only work if we use that E = m·v2 energy concept which, you’ll agree, doesn’t make much sense—at first, at least. Again: what’s going on? Well… Same honest answer: the f = E/h and λ = h/p equations cannot be related—or at least not so easily—because the wave equation itself is not so easy.

Let’s review the basics once again.

The wavefunction

The amplitude of a particle is represented by a wavefunction. If we have no information whatsoever on its position, then we usually write that wavefunction as the following complex-valued exponential:

ψ(x, t) = a·e−i·[(E/ħ)·t − (p/ħ)∙x] = a·e−i·(ω·t − k∙x) = a·ei(k∙x−ω·t) = a·eiθ = a·(cosθ + i·sinθ)

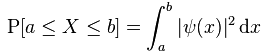

θ is the so-called phase of our wavefunction and, as you can see, it’s the argument of a wavefunction indeed, with temporal frequency ω and spatial frequency k (if we choose our x-axis so its direction is the same as the direction of k, then we can substitute the k and x vectors for the k and x scalars, so that’s what we’re doing here). Now, we know we shouldn’t worry too much about a, because that’s just some normalization constant (remember: all probabilities have to add up to one). However, let’s quickly develop some logic here. Taking the absolute square of this wavefunction gives us the probability of our particle being somewhere in space at some point in time. So we get the probability as a function of x and t. We write:

P(x ,t) = |a·e−i·[(E/ħ)·t − (p/ħ)∙x]|2 = a2

As all probabilities have to add up to one, we must assume we’re looking at some box in spacetime here. So, if the length of our box is Δx = x2 − x1, then (Δx)·a2 = (x2−x1)·a2 = 1 ⇔ Δx = 1/a2. [We obviously simplify the analysis by assuming a one-dimensional space only here, but the gist of the argument is essentially correct.] So, freezing time (i.e. equating t to some point t = t0), we get the following probability density function:

That’s simple enough. The point is: the two de Broglie equations f = E/h and λ = h/p give us the temporal and spatial frequencies in that ψ(x, t) = a·e−i·[(E/ħ)·t − (p/ħ)∙x] relation. As you can see, that’s an equation that implies a much more complicated relationship between E/ħ = ω and p/ħ = k. Or… Well… Much more complicated than what one would think of at first.

To appreciate what’s being represented here, it’s good to play a bit. We’ll continue with our simple exponential above, which also illustrates how we usually analyze those wavefunctions: we either assume we’re looking at the wavefunction in space at some fixed point in time (t = t0) or, else, at how the wavefunction changes in time at some fixed point in space (x = x0). Of course, we know that Einstein told us we shouldn’t do that: space and time are related and, hence, we should try to think of spacetime, i.e. some ‘kind of union’ of space and time—as Minkowski famously put it. However, when everything is said and done, mere mortals like us are not so good at that, and so we’re sort of condemned to try to imagine things using the classical cut-up of things. 🙂 So we’ll just an online graphing tool to play with that a·ei(k∙x−ω·t) = a·eiθ = a·(cosθ + i·sinθ) formula.

Compare the following two graps, for example. Just imagine we either look at how the wavefunction behaves at some point in space, with the time fixed at some point t = t0, or, alternatively, that we look at how the wavefunction behaves in time at some point in space x = x0. As you can see, increasing k = p/ħ or increasing ω = E/ħ gives the wavefunction a higher ‘density’ in space or, alternatively, in time.

That makes sense, intuitively. In fact, when thinking about how the energy, or the momentum, affects the shape of the wavefunction, I am reminded of an airplane propeller: as it spins, faster and faster, it gives the propeller some ‘density’, in space as well as in time, as its blades cover more space in less time. It’s an interesting analogy: it helps—me, at least—to think through what that wavefunction might actually represent.

That makes sense, intuitively. In fact, when thinking about how the energy, or the momentum, affects the shape of the wavefunction, I am reminded of an airplane propeller: as it spins, faster and faster, it gives the propeller some ‘density’, in space as well as in time, as its blades cover more space in less time. It’s an interesting analogy: it helps—me, at least—to think through what that wavefunction might actually represent.

So as to stimulate your imagination even more, you should also think of representing the real and complex part of that ψ = a·ei(k∙x−ω·t) = a·eiθ = a·(cosθ + i·sinθ) formula in a different way. In the graphs above, we just showed the sine and cosine in the same plane but, as you know, the real and the imaginary axis are orthogonal, so Euler’s formula a·eiθ = a·(cosθ + i·sinθ) = a·cosθ + i·a·sinθ = Re(ψ) + i·Im(ψ) may also be graphed as follows:

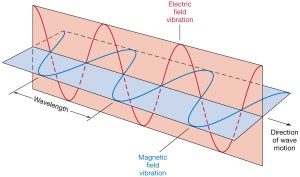

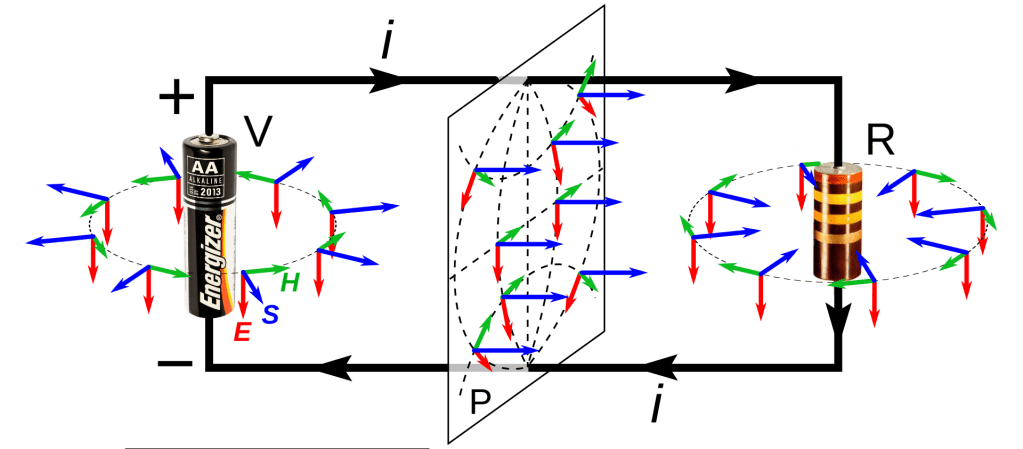

The illustration above should make you think of yet another illustration you’ve probably seen like a hundred times before: the electromagnetic wave, propagating through space as the magnetic and electric field induce each other, as illustrated below. However, there’s a big difference: Euler’s formula incorporates a phase shift—remember: sinθ = cos(θ − π/2)—and you don’t have that in the graph below. The difference is much more fundamental, however: it’s really hard to see how one could possibly relate the magnetic and electric field to the real and imaginary part of the wavefunction respectively. Having said that, the mathematical similarity makes one think!

Of course, you should remind yourself of what E and B stand for: they represent the strength of the electric (E) and magnetic (B) field at some point x at some time t. So you shouldn’t think of those wavefunctions above as occupying some three-dimensional space. They don’t. Likewise, our wavefunction ψ(x, t) does not occupy some physical space: it’s some complex number—an amplitude that’s associated with each and every point in spacetime. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, the visuals make one think and, as such, do help us as we try to understand all of this in a more intuitive way.

Let’s now look at that energy-momentum relationship once again, but using the wavefunction, rather than those two de Broglie relations.

Energy and momentum in the wavefunction

I am not going to talk about uncertainty here. You know that Spiel. If there’s uncertainty, it’s in the energy or the momentum, or in both. The uncertainty determines the size of that ‘box’ (in spacetime) in which we hope to find our particle, and it’s modeled by a splitting of the energy levels. We’ll say the energy of the particle may be E0, but it might also be some other value, which we’ll write as En = E0 ± n·ħ. The thing to note is that energy levels will always be separated by some integer multiple of ħ, so ħ is, effectively , the quantum of energy for all practical—and theoretical—purposes. We then super-impose the various wave equations to get a wave function that might—or might not—resemble something like this:

Who knows? 🙂 In any case, that’s not what I want to talk about here. Let’s repeat the basics once more: if we write our wavefunction a·e−i·[(E/ħ)·t − (p/ħ)∙x] as a·e−i·[ω·t − k∙x], we refer to ω = E/ħ as the temporal frequency, i.e. the frequency of our wavefunction in time (i.e. the frequency it has if we keep the position fixed), and to k = p/ħ as the spatial frequency (i.e. the frequency of our wavefunction in space (so now we stop the clock and just look at the wave in space). Now, let’s think about the energy concept first. The energy of a particle is generally thought of to consist of three parts:

Who knows? 🙂 In any case, that’s not what I want to talk about here. Let’s repeat the basics once more: if we write our wavefunction a·e−i·[(E/ħ)·t − (p/ħ)∙x] as a·e−i·[ω·t − k∙x], we refer to ω = E/ħ as the temporal frequency, i.e. the frequency of our wavefunction in time (i.e. the frequency it has if we keep the position fixed), and to k = p/ħ as the spatial frequency (i.e. the frequency of our wavefunction in space (so now we stop the clock and just look at the wave in space). Now, let’s think about the energy concept first. The energy of a particle is generally thought of to consist of three parts:

- The particle’s rest energy m0c2, which de Broglie referred to as internal energy (Eint): it includes the rest mass of the ‘internal pieces’, as Feynman puts it (now we call those ‘internal pieces’ quarks), as well as their binding energy (i.e. the quarks’ interaction energy);

- Any potential energy it may have because of some field (so de Broglie was not assuming the particle was traveling in free space), which we’ll denote by U, and note that the field can be anything—gravitational, electromagnetic: it’s whatever changes the energy because of the position of the particle;

- The particle’s kinetic energy, which we write in terms of its momentum p: m·v2/2 = m2·v2/(2m) = (m·v)2/(2m) = p2/(2m).

So we have one energy concept here (the rest energy) that does not depend on the particle’s position in spacetime, and two energy concepts that do depend on position (potential energy) and/or how that position changes because of its velocity and/or momentum (kinetic energy). The two last bits are related through the energy conservation principle. The total energy is E = mvc2, of course—with the little subscript (v) ensuring the mass incorporates the equivalent mass of the particle’s kinetic energy.

So what? Well… In my post on quantum tunneling, I drew attention to the fact that different potentials , so different potential energies (indeed, as our particle travels one region to another, the field is likely to vary) have no impact on the temporal frequency. Let me re-visit the argument, because it’s an important one. Imagine two different regions in space that differ in potential—because the field has a larger or smaller magnitude there, or points in a different direction, or whatever: just different fields, which corresponds to different values for U1 and U2, i.e. the potential in region 1 versus region 2. Now, the different potential will change the momentum: the particle will accelerate or decelerate as it moves from one region to the other, so we also have a different p1 and p2. Having said that, the internal energy doesn’t change, so we can write the corresponding amplitudes, or wavefunctions, as:

- ψ1(θ1) = Ψ1(x, t) = a·e−iθ1 = a·e−i[(Eint + p12/(2m) + U1)·t − p1∙x]/ħ

- ψ2(θ2) = Ψ2(x, t) = a·e−iθ2 = a·e−i[(Eint + p22/(2m) + U2)·t − p2∙x]/ħ

Now how should we think about these two equations? We are definitely talking different wavefunctions. However, their temporal frequencies ω1 = Eint + p12/(2m) + U1 and ω1 = Eint + p22/(2m) + U2 must be the same. Why? Because of the energy conservation principle—or its equivalent in quantum mechanics, I should say: the temporal frequency f or ω, i.e. the time-rate of change of the phase of the wavefunction, does not change: all of the change in potential, and the corresponding change in kinetic energy, goes into changing the spatial frequency, i.e. the wave number k or the wavelength λ, as potential energy becomes kinetic or vice versa. The sum of the potential and kinetic energy doesn’t change, indeed. So the energy remains the same and, therefore, the temporal frequency does not change. In fact, we need this quantum-mechanical equivalent of the energy conservation principle to calculate how the momentum and, hence, the spatial frequency of our wavefunction, changes. We do so by boldly equating ω1 = Eint + p12/(2m) + U1 and ω2 = Eint + p22/(2m) + U2, and so we write:

ω1 = ω2 ⇔ Eint + p12/(2m) + U1 = Eint + p22/(2m) + U2

⇔ p12/(2m) − p22/(2m) = U2 – U1 ⇔ p22 = (2m)·[p12/(2m) – (U2 – U1)]

⇔ p2 = (p12 – 2m·ΔU )1/2

We played with this in a previous post, assuming that p12 is larger than 2m·ΔU, so as to get a positive number on the right-hand side of the equation for p22, so then we can confidently take the positive square root of that (p12 – 2m·ΔU ) expression to calculate p2. For example, when the potential difference ΔU = U2 – U1 was negative, so ΔU < 0, then we’re safe and sure to get some real positive value for p2.

Having said that, we also contemplated the possibility that p22 = p12 – 2m·ΔU was negative, in which case p2 has to be some pure imaginary number, which we wrote as p2 = i·p’ (so p’ (read: p prime) is a real positive number here). We could work with that: it resulted in an exponentially decreasing factor e−p’·x/ħ that ended up ‘killing’ the wavefunction in space. However, its limited existence still allowed particles to ‘tunnel’ through potential energy barriers, thereby explaining the quantum-mechanical tunneling phenomenon.

This is rather weird—at first, at least. Indeed, one would think that, because of the E/ħ = ω equation, any change in energy would lead to some change in ω. But no! The total energy doesn’t change, and the potential and kinetic energy are like communicating vessels: any change in potential energy is associated with a change in p, and vice versa. It’s a really funny thing. It helps to think it’s because the potential depends on position only, and so it should not have an impact on the temporal frequency of our wavefunction. Of course, it’s equally obvious that the story would change drastically if the potential would change with time, but… Well… We’re not looking at that right now. In short, we’re assuming energy is being conserved in our quantum-mechanical system too, and so that implies what’s described above: no change in ω, but we obviously do have changes in p whenever our particle goes from one region in space to another, and the potentials differ. So… Well… Just remember: the energy conservation principle implies that the temporal frequency of our wave function doesn’t change. Any change in potential, as our particle travels from one place to another, plays out through the momentum.

Now that we know that, let’s look at those de Broglie relations once again.

Re-visiting the de Broglie relations

As mentioned above, we usually think in one dimension only: we either freeze time or, else, we freeze space. If we do that, we can derive some funny new relationships. Let’s first simplify the analysis by re-writing the argument of the wavefunction as:

θ = E·t − p·x

Of course, you’ll say: the argument of the wavefunction is not equal to E·t − p·x: it’s (E/ħ)·t − (p/ħ)∙x. Moreover, θ should have a minus sign in front. Well… Yes, you’re right. We should put that 1/ħ factor in front, but we can change units, and so let’s just measure both E as well as p in units of ħ here. We can do that. No worries. And, yes, the minus sign should be there—Nature choose a clockwise direction for θ—but that doesn’t matter for the analysis hereunder.

The E·t − p·x expression reminds one of those invariant quantities in relativity theory. But let’s be precise here. We’re thinking about those so-called four-vectors here, which we wrote as pμ = (E, px, py, pz) = (E, p) and xμ = (t, x, y, z) = (t, x) respectively. [Well… OK… You’re right. We wrote those four-vectors as pμ = (E, px·c , py·c, pz·c) = (E, p·c) and xμ = (c·t, x, y, z) = (t, x). So what we write is true only if we measure time and distance in equivalent units so we have c = 1. So… Well… Let’s do that and move on.] In any case, what was invariant was not E·t − p·x·c or c·t − x (that’s a nonsensical expression anyway: you cannot subtract a vector from a scalar), but pμ2 = pμpμ = E2 − (p·c)2 = E2 − p2·c2 = E2 − (px2 + py2 + pz2)·c2 and xμ2 = xμxμ = (c·t)2 − x2 = c2·t2 − (x2 + y2 + z2) respectively. [Remember pμpμ and xμxμ are four-vector dot products, so they have that +— signature, unlike the p2 and x2 or a·b dot products, which are just a simple sum of the squared components.] So… Well… E·t − p·x is not an invariant quantity. Let’s try something else.

Let’s re-simplify by equating ħ as well as c to one again, so we write: ħ = c = 1. [You may wonder if it is possible to ‘normalize’ both physical constants simultaneously, but the answer is yes. The Planck unit system is an example.] then our relativistic energy-momentum relationship can be re-written as E/p = 1/v. [If c would not be one, we’d write: E·β = p·c, with β = v/c. So we got E/p = c/β. We referred to β as the relative velocity of our particle: it was the velocity, but measured as a ratio of the speed of light. So here it’s the same, except that we use the velocity symbol v now for that ratio.]

Now think of a particle moving in free space, i.e. without any fields acting on it, so we don’t have any potential changing the spatial frequency of the wavefunction of our particle, and let’s also assume we choose our x-axis such that it’s the direction of travel, so the position vector (x) can be replaced by a simple scalar (x). Finally, we will also choose the origin of our x-axis such that x = 0 zero when t = 0, so we write: x(t = 0) = 0. It’s obvious then that, if our particle is traveling in spacetime with some velocity v, then the ratio of its position x and the time t that it’s been traveling will always be equal to v = x/t. Hence, for that very special position in spacetime (t, x = v·t) – so we’re talking the actual position of the particle in spacetime here – we get: θ = E·t − p·x = E·t − p·v·t = E·t − m·v·v·t= (E − m∙v2)·t. So… Well… There we have the m∙v2 factor.

The question is: what does it mean? How do we interpret this? I am not sure. When I first jotted this thing down, I thought of choosing a different reference potential: some negative value such that it ensures that the sum of kinetic, rest and potential energy is zero, so I could write E = 0 and then the wavefunction would reduce to ψ(t) = e−i·m∙v2·t. Feynman refers to that as ‘choosing the zero of our energy scale such that E = 0’, and you’ll find this in many other works too. However, it’s not that simple. Free space is free space: if there’s no change in potential from one region to another, then the concept of some reference point for the potential becomes meaningless. There is only rest energy and kinetic energy, then. The total energy reduces to E = m (because we chose our units such that c = 1 and, therefore, E = mc2 = m·12 = m) and so our wavefunction reduces to:

ψ(t) = a·e−i·m·(1 − v2)·t

We can’t reduce this any further. The mass is the mass: it’s a measure for inertia, as measured in our inertial frame of reference. And the velocity is the velocity, of course—also as measured in our frame of reference. We can re-write it, of course, by substituting t for t = x/v, so we get:

ψ(x) = a·e−i·m·(1/v − v)·x

For both functions, we get constant probabilities, but a wavefunction that’s ‘denser’ for higher values of m. The (1 − v2) and (1/v − v) factors are different, however: these factors becomes smaller for higher v, so our wavefunction becomes less dense for higher v. In fact, for v = 1 (so for travel at the speed of light, i.e. for photons), we get that ψ(t) = ψ(x) = e0 = 1. [You should use the graphing tool once more, and you’ll see the imaginary part, i.e. the sine of the a·(cosθ + i·sinθ) expression, just vanishes, as sinθ = 0 for θ = 0.]

The wavefunction and relativistic length contraction

Are exercises like this useful? As mentioned above, these constant probability wavefunctions are a bit nonsensical, so you may wonder why I wrote what I wrote. There may be no real conclusion, indeed: I was just fiddling around a bit, and playing with equations and functions. I feel stuff like this helps me to understand what that wavefunction actually is somewhat better. If anything, it does illustrate that idea of the ‘density’ of a wavefunction, in space or in time. What we’ve been doing by substituting x for x = v·t or t for t = x/v is showing how, when everything is said and done, the mass and the velocity of a particle are the actual variables determining that ‘density’ and, frankly, I really like that ‘airplane propeller’ idea as a pedagogic device. In fact, I feel it may be more than just a pedagogic device, and so I’ll surely re-visit it—once I’ve gone through the rest of Feynman’s Lectures, that is. 🙂

That brings me to what I added in the title of this post: relativistic length contraction. You’ll wonder why I am bringing that into a discussion like this. Well… Just play a bit with those (1 − v2) and (1/v − v) factors. As mentioned above, they decrease the density of the wavefunction. In other words, it’s like space is being ‘stretched out’. Also, it can’t be a coincidence we find the same (1 − v2) factor in the relativistic length contraction formula: L = L0·√(1 − v2), in which L0 is the so-called proper length (i.e. the length in the stationary frame of reference) and v is the (relative) velocity of the moving frame of reference. Of course, we also find it in the relativistic mass formula: m = mv = m0/√(1−v2). In fact, things become much more obvious when substituting m for m0/√(1−v2) in that ψ(t) = e−i·m·(1 − v2)·t function. We get:

ψ(t) = a·e−i·m·(1 − v2)·t = a·e−i·m0·√(1−v2)·t

Well… We’re surely getting somewhere here. What if we go back to our original ψ(x, t) = a·e−i·[(E/ħ)·t − (p/ħ)∙x] function? Using natural units once again, that’s equivalent to:

ψ(x, t) = a·e−i·(m·t − p∙x) = a·e−i·[(m0/√(1−v2))·t − (m0·v/√(1−v2)∙x)

= a·e−i·[m0/√(1−v2)]·(t − v∙x)

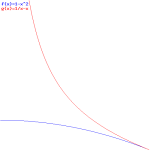

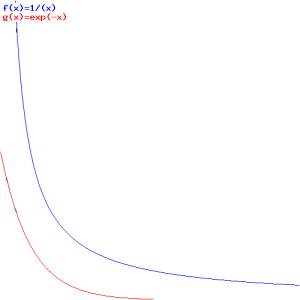

Interesting! We’ve got a wavefunction that’s a function of x and t, but with the rest mass (or rest energy) and velocity as parameters! Now that really starts to make sense. Look at the (blue) graph for that 1/√(1−v2) factor: it goes from one (1) to infinity (∞) as v goes from 0 to 1 (remember we ‘normalized’ v: it’s a ratio between 0 and 1 now). So that’s the factor that comes into play for t. For x, it’s the red graph, which has the same shape but goes from zero (0) to infinity (∞) as v goes from 0 to 1.

Now that makes sense: the ‘density’ of the wavefunction, in time and in space, increases as the velocity v increases. In space, that should correspond to the relativistic length contraction effect: it’s like space is contracting, as the velocity increases and, therefore, the length of the object we’re watching contracts too. For time, the reasoning is a bit more complicated: it’s our time that becomes more dense and, therefore, our clock that seems to tick faster.

Now that makes sense: the ‘density’ of the wavefunction, in time and in space, increases as the velocity v increases. In space, that should correspond to the relativistic length contraction effect: it’s like space is contracting, as the velocity increases and, therefore, the length of the object we’re watching contracts too. For time, the reasoning is a bit more complicated: it’s our time that becomes more dense and, therefore, our clock that seems to tick faster.

[…]

I know I need to explore this further—if only so as to assure you I have not gone crazy. Unfortunately, I have no time to do that right now. Indeed, from time to time, I need to work on other stuff besides this physics ‘hobby’ of mine.

Post scriptum 1: As for the E = m·v2 formula, I also have a funny feeling that it might be related to the fact that, in quantum mechanics, both the real and imaginary part of the oscillation actually matter. You’ll remember that we’d represent any oscillator in physics by a complex exponential, because it eased our calculations. So instead of writing A = A0·cos(ωt + Δ), we’d write: A = A0·ei(ωt + Δ) = A0·cos(ωt + Δ) + i·A0·sin(ωt + Δ). When calculating the energy or intensity of a wave, however, we couldn’t just take the square of the complex amplitude of the wave – remembering that E ∼ A2. No! We had to get back to the real part only, i.e. the cosine or the sine only. Now the mean (or average) value of the squared cosine function (or a squared sine function), over one or more cycles, is 1/2, so the mean of A2 is equal to 1/2 = A02. cos(ωt + Δ). I am not sure, and it’s probably a long shot, but one must be able to show that, if the imaginary part of the oscillation would actually matter – which is obviously the case for our matter-wave – then 1/2 + 1/2 is obviously equal to 1. I mean: try to think of an image with a mass attached to two springs, rather than one only. Does that make sense? 🙂 […] I know: I am just freewheeling here. 🙂

Post scriptum 2: The other thing that this E = m·v2 equation makes me think of is – curiously enough – an eternally expanding spring. Indeed, the kinetic energy of a mass on a spring and the potential energy that’s stored in the spring always add up to some constant, and the average potential and kinetic energy are equal to each other. To be precise: 〈K.E.〉 + 〈P.E.〉 = (1/4)·k·A2 + (1/4)·k·A2 = k·A2/2. It means that, on average, the total energy of the system is twice the average kinetic energy (or potential energy). You’ll say: so what? Well… I don’t know. Can we think of a spring that expands eternally, with the mass on its end not gaining or losing any speed? In that case, v is constant, and the total energy of the system would, effectively, be equal to Etotal = 2·〈K.E.〉 = (1/2)·m·v2/2 = m·v2.

Post scriptum 3: That substitution I made above – substituting x for x = v·t – is kinda weird. Indeed, if that E = m∙v2 equation makes any sense, then E − m∙v2 = 0, of course, and, therefore, θ = E·t − p·x = E·t − p·v·t = E·t − m·v·v·t= (E − m∙v2)·t = 0·t = 0. So the argument of our wavefunction is 0 and, therefore, we get a·e0 = a for our wavefunction. It basically means our particle is where it is. 🙂

Post scriptum 4: This post scriptum – no. 4 – was added later—much later. On 29 February 2016, to be precise. The solution to the ‘riddle’ above is actually quite simple. We just need to make a distinction between the group and the phase velocity of our complex-valued wave. The solution came to me when I was writing a little piece on Schrödinger’s equation. I noticed that we do not find that weird E = m∙v2 formula when substituting ψ for ψ = ei(kx − ωt) in Schrödinger’s equation, i.e. in:

Let me quickly go over the logic. To keep things simple, we’ll just assume one-dimensional space, so ∇2ψ = ∂2ψ/∂x2. The time derivative on the left-hand side is ∂ψ/∂t = −iω·ei(kx − ωt). The second-order derivative on the right-hand side is ∂2ψ/∂x2 = (ik)·(ik)·ei(kx − ωt) = −k2·ei(kx − ωt) . The ei(kx − ωt) factor on both sides cancels out and, hence, equating both sides gives us the following condition:

−iω = −(iħ/2m)·k2 ⇔ ω = (ħ/2m)·k2

Substituting ω = E/ħ and k = p/ħ yields:

E/ħ = (ħ/2m)·p2/ħ2 = m2·v2/(2m·ħ) = m·v2/(2ħ) ⇔ E = m·v2/2

In short: the E = m·v2/2 is the correct formula. It must be, because… Well… Because Schrödinger’s equation is a formula we surely shouldn’t doubt, right? So the only logical conclusion is that we must be doing something wrong when multiplying the two de Broglie equations. To be precise: our v = f·λ equation must be wrong. Why? Well… It’s just something one shouldn’t apply to our complex-valued wavefunction. The ‘correct’ velocity formula for the complex-valued wavefunction should have that 1/2 factor, so we’d write 2·f·λ = v to make things come out alright. But where would this formula come from? The period of cosθ + isinθ is the period of the sine and cosine function: cos(θ+2π) + isin(θ+2π) = cosθ + isinθ, so T = 2π and f = 1/T = 1/2π do not change.

But so that’s a mathematical point of view. From a physical point of view, it’s clear we got two oscillations for the price of one: one ‘real’ and one ‘imaginary’—but both are equally essential and, hence, equally ‘real’. So the answer must lie in the distinction between the group and the phase velocity when we’re combining waves. Indeed, the group velocity of a sum of waves is equal to vg = dω/dk. In this case, we have:

vg = d[E/ħ]/d[p/ħ] = dE/dp

We can now use the kinetic energy formula to write E as E = m·v2/2 = p·v/2. Now, v and p are related through m (p = m·v, so v = p/m). So we should write this as E = m·v2/2 = p2/(2m). Substituting E and p = m·v in the equation above then gives us the following:

dω/dk = d[p2/(2m)]/dp = 2p/(2m) = vg = v

However, for the phase velocity, we can just use the vp = ω/k formula, which gives us that 1/2 factor:

vp = ω/k = (E/ħ)/(p/ħ) = E/p = (m·v2/2)/(m·v) = v/2

Bingo! Riddle solved! 🙂 Isn’t it nice that our formula for the group velocity also applies to our complex-valued wavefunction? I think that’s amazing, really! But I’ll let you think about it. 🙂