Pre-script (dated 26 June 2020): This post has become less relevant (even irrelevant, perhaps) because my views on all things quantum-mechanical have evolved significantly as a result of my progression towards a more complete realist (classical) interpretation of quantum physics. I keep blog posts like these mainly because I want to keep track of where I came from. I might review them one day, but I currently don’t have the time or energy for it. 🙂

Original post:

This is my third and final comments on Feynman’s popular little booklet: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, also known as Feynman’s Lectures on Quantum Electrodynamics (QED).

The origin of this short lecture series is quite moving: the death of Alix G. Mautner, a good friend of Feynman’s. She was always curious about physics but her career was in English literature and so she did not manage the math. Hence, Feynman introduces this 1985 publication by writing: “Here are the lectures I really prepared for Alix, but unfortunately I can’t tell them to her directly, now.”

Alix Mautner died from a brain tumor, and it is her husband, Leonard Mautner, who sponsored the QED lectures series at the UCLA, which Ralph Leigton transcribed and published as the booklet that we’re talking about here. Feynman himself died a few years later, at the relatively young age of 69. Tragic coincidence: he died of cancer too. Despite all this weirdness, Feynman’s QED never quite got the same iconic status of, let’s say, Stephen Hawking’s Brief History of Time. I wonder why, but the answer to that question is probably in the realm of chaos theory. 🙂 I actually just saw the movie on Stephen Hawking’s life (The Theory of Everything), and I noted another strange coincidence: Jane Wilde, Hawking’s first wife, also has a PhD in literature. It strikes me that, while the movie documents that Jane Wilde gave Hawking three children, after which he divorced her to marry his nurse, Elaine, the movie does not mention that he separated from Elaine too, and that he has some kind of ‘working relationship’ with Jane again.

Hmm… What to say? I should get back to quantum mechanics here or, to be precise, to quantum electrodynamics.

One reason why Feynman’s Strange Theory of Light and Matter did not sell like Hawking’s Brief History of Time, might well be that, in some places, the text is not entirely accurate. Why? Who knows? It would make for an interesting PhD thesis in History of Science. Unfortunately, I have no time for such PhD thesis. Hence, I must assume that Richard Feynman simply didn’t have much time or energy left to correct some of the writing of Ralph Leighton, who transcribed and edited these four short lectures a few years before Feynman’s death. Indeed, when everything is said and done, Ralph Leighton is not a physicist and, hence, I think he did compromise – just a little bit – on accuracy for the sake of readability. Ralph Leighton’s father, Robert Leighton, an eminent physicist who worked with Feynman, would probably have done a much better job.

I feel that one should not compromise on accuracy, even when trying to write something reader-friendly. That’s why I am writing this blog, and why I am writing three posts specifically on this little booklet. Indeed, while I’d warmly recommend that little book on QED as an excellent non-mathematical introduction to the weird world of quantum mechanics, I’d also say that, while Ralph Leighton’s story is great, it’s also, in some places, not entirely accurate indeed.

So… Well… I want to do better than Ralph Leighton here. Nothing more. Nothing less. 🙂 Let’s go for it.

I. Probability amplitudes: what are they?

The greatest achievement of that little QED publication is that it manages to avoid any reference to wave functions and other complicated mathematical constructs: all of the complexity of quantum mechanics is reduced to three basic events or actions and, hence, three basic amplitudes which are represented as ‘arrows’—literally.

Now… Well… You may or may not know that a (probability) amplitude is actually a complex number, but it’s not so easy to intuitively understand the concept of a complex number. In contrast, everyone easily ‘gets’ the concept of an ‘arrow’. Hence, from a pedagogical point of view, representing complex numbers by some ‘arrow’ is truly a stroke of genius.

Whatever we call it, a complex number or an ‘arrow’, a probability amplitude is something with (a) a magnitude and (b) a phase. As such, it resembles a vector, but it’s not quite the same, if only because we’ll impose some restrictions on the magnitude. But I shouldn’t get ahead of myself. Let’s start with the basics.

A magnitude is some real positive number, like a length, but you should not associate it with some spatial dimension in physical space: it’s just a number. As for the phase, we could associate that concept with some direction but, again, you should just think of it as a direction in a mathematical space, not in the real (physical) space.

Let me insert a parenthesis here. If I say the ‘real’ or ‘physical’ space, I mean the space in which the electrons and photons and all other real-life objects that we’re looking at exist and move. That’s a non-mathematical definition. In fact, in math, the real space is defined as a coordinate space, with sets of real numbers (vectors) as coordinates, so… Well… That’s a mathematical space only, not the ‘real’ (physical) space. So the real (vector) space is not real. 🙂 The mathematical real space may, or may not, accurately describe the real (physical) space. Indeed, you may have heard that physical space is curved because of the presence of massive objects, which means that the real coordinate space will actually not describe it very accurately. I know that’s a bit confusing but I hope you understand what I mean: if mathematicians talk about the real space, they do not mean the real space. They refer to a vector space, i.e. a mathematical construct. To avoid confusion, I’ll use the term ‘physical space’ rather than ‘real’ space in the future. So I’ll let the mathematicians get away with using the term ‘real space’ for something that isn’t real actually. 🙂

End of digression. Let’s discuss these two mathematical concepts – magnitude and phase – somewhat more in detail.

A. The magnitude

Let’s start with the magnitude or ‘length’ of our arrow. We know that we have to square these lengths to find some probability, i.e. some real number between 0 and 1. Hence, the length of our arrows cannot be larger than one. That’s the restriction I mentioned already, and this ‘normalization’ condition reinforces the point that these ‘arrows’ do not have any spatial dimension (not in any real space anyway): they represent a function. To be specific, they represent a wavefunction.

If we’d be talking complex numbers instead of ‘arrows’, we’d say the absolute value of the complex number cannot be larger than one. We’d also say that, to find the probability, we should take the absolute square of the complex number, so that’s the square of the magnitude or absolute value of the complex number indeed. We cannot just square the complex number: it has to be the square of the absolute value.

Why? Well… Just write it out. [You can skip this section if you’re not interested in complex numbers, but I would recommend you try to understand. It’s not that difficult. Indeed, if you’re reading this, you’re most likely to understand something of complex numbers and, hence, you should be able to work your way through it. Just remember that a complex number is like a two-dimensional number, which is why it’s sometimes written using bold-face (z), rather than regular font (z). However, I should immediately add this convention is usually not followed. I like the boldface though, and so I’ll try to use it in this post.] The square of a complex number z = a + bi is equal to z2 = a2 + 2abi – b2, while the square of its absolute value (i.e. the absolute square) is |z|2 = [√(a2 + b2)]2 = a2 + b2. So you can immediately see that the square and the absolute square of a complex numbers are two very different things indeed: it’s not only the 2abi term, but there’s also the minus sign in the first expression, because of the i2 = –1 factor. In case of doubt, always remember that the square of a complex number may actually yield a negative number, as evidenced by the definition of the imaginary unit itself: i2 = –1.

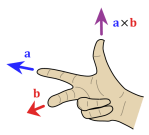

End of digression. Feynman and Leighton manage to avoid any reference to complex numbers in that short series of four lectures and, hence, all they need to do is explain how one squares a length. Kids learn how to do that when making a square out of rectangular paper: they’ll fold one corner of the paper until it meets the opposite edge, forming a triangle first. They’ll then cut or tear off the extra paper, and then unfold. Done. [I could note that the folding is a 90 degree rotation of the original length (or width, I should say) which, in mathematical terms, is equivalent to multiplying that length with the imaginary unit (i). But I am sure the kids involved would think I am crazy if I’d say this. 🙂 So let me get back to Feynman’s arrows.

B. The phase

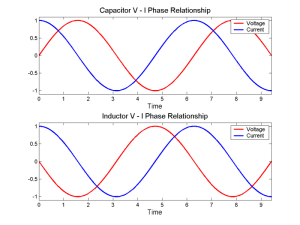

Feynman and Leighton’s second pedagogical stroke of genius is the metaphor of the ‘stopwatch’ and the ‘stopwatch hand’ for the variable phase. Indeed, although I think it’s worth explaining why z = a + bi = rcosφ + irsinφ in the illustration below can be written as z = reiφ = |z|eiφ, understanding Euler’s representation of complex number as a complex exponential requires swallowing a very substantial piece of math and, if you’d want to do that, I’ll refer you to one of my posts on complex numbers).

The metaphor of the stopwatch represents a periodic function. To be precise, it represents a sinusoid, i.e. a smooth repetitive oscillation. Now, the stopwatch hand represents the phase of that function, i.e. the φ angle in the illustration above. That angle is a function of time: the speed with which the stopwatch turns is related to some frequency, i.e. the number of oscillations per unit of time (i.e. per second).

You should now wonder: what frequency? What oscillations are we talking about here? Well… As we’re talking photons and electrons here, we should distinguish the two:

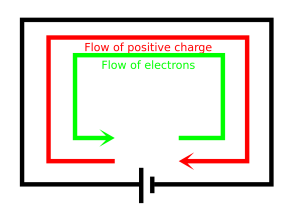

- For photons, the frequency is given by Planck’s energy-frequency relation, which relates the energy (E) of a photon (1.5 to 3.5 eV for visible light) to its frequency (ν). It’s a simple proportional relation, with Planck’s constant (h) as the proportionality constant: E = hν, or ν = E/h.

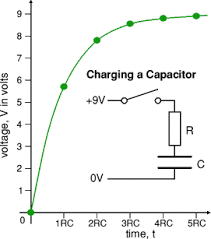

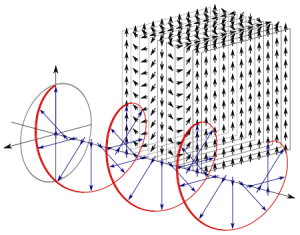

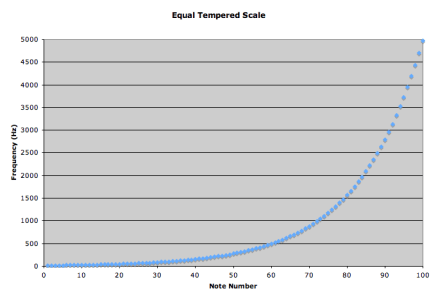

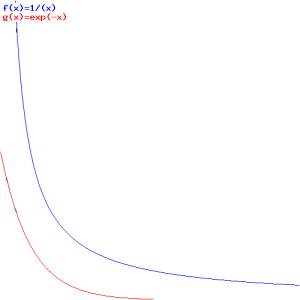

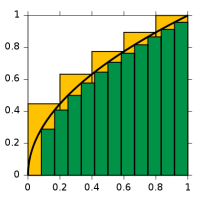

- For electrons, we have the de Broglie relation, which looks similar to the Planck relation (E = hf, or f = E/h) but, as you know, it’s something different. Indeed, these so-called matter waves are not so easy to interpret because there actually is no precise frequency f. In fact, the matter wave representing some particle in space will consist of a potentially infinite number of waves, all superimposed one over another, as illustrated below.

For the sake of accuracy, I should mention that the animation above has its limitations: the wavetrain is complex-valued and, hence, has a real as well as an imaginary part, so it’s something like the blob underneath. Two functions in one, so to speak: the imaginary part follows the real part with a phase difference of 90 degrees (or π/2 radians). Indeed, if the wavefunction is a regular complex exponential reiθ, then rsin(φ–π/2) = rcos(φ), which proves the point: we have two functions in one here. 🙂 I am actually just repeating what I said before already: the probability amplitude, or the wavefunction, is a complex number. You’ll usually see it written as Ψ (psi) or Φ (phi). Here also, using boldface (Ψ or Φ instead of Ψ or Φ) would usefully remind the reader that we’re talking something ‘two-dimensional’ (in mathematical space, that is), but this convention is usually not followed.

In any case… Back to frequencies. The point to note is that, when it comes to analyzing electrons (or any other matter-particle), we’re dealing with a range of frequencies f really (or, what amounts to the same, a range of wavelengths λ) and, hence, we should write Δf = ΔE/h, which is just one of the many expressions of the Uncertainty Principle in quantum mechanics.

Now, that’s just one of the complications. Another difficulty is that matter-particles, such as electrons, have some rest mass, and so that enters the energy equation as well (literally). Last but not least, one should distinguish between the group velocity and the phase velocity of matter waves. As you can imagine, that makes for a very complicated relationship between ‘the’ wavelength and ‘the’ frequency. In fact, what I write above should make it abundantly clear that there’s no such thing as the wavelength, or the frequency: it’s a range really, related to the fundamental uncertainty in quantum physics. I’ll come back to that, and so you shouldn’t worry about it here. Just note that the stopwatch metaphor doesn’t work very well for an electron!

In his postmortem lectures for Alix Mautner, Feynman avoids all these complications. Frankly, I think that’s a missed opportunity because I do not think it’s all that incomprehensible. In fact, I write all that follows because I do want you to understand the basics of waves. It’s not difficult. High-school math is enough here. Let’s go for it.

One turn of the stopwatch corresponds to one cycle. One cycle, or 1 Hz (i.e. one oscillation per second) covers 360 degrees or, to use a more natural unit, 2π radians. [Why is radian a more natural unit? Because it measures an angle in terms of the distance unit itself, rather than in arbitrary 1/360 cuts of a full circle. Indeed, remember that the circumference of the unit circle is 2π.] So our frequency ν (expressed in cycles per second) corresponds to a so-called angular frequency ω = 2πν. From this formula, it should be obvious that ω is measured in radians per second.

We can also link this formula to the period of the oscillation, T, i.e. the duration of one cycle. T = 1/ν and, hence, ω = 2π/T. It’s all nicely illustrated below. [And, yes, it’s an animation from Wikipedia: nice and simple.]

The easy math above now allows us to formally write the phase of a wavefunction – let’s denote the wavefunction as φ (phi), and the phase as θ (theta) – as a function of time (t) using the angular frequency ω. So we can write: θ = ωt = 2π·ν·t. Now, the wave travels through space, and the two illustrations above (i.e. the one with the super-imposed waves, and the one with the complex wave train) would usually represent a wave shape at some fixed point in time. Hence, the horizontal axis is not t but x. Hence, we can and should write the phase not only as a function of time but also of space. So how do we do that? Well… If the hypothesis is that the wave travels through space at some fixed speed c, then its frequency ν will also determine its wavelength λ. It’s a simple relationship: c = λν (the number of oscillations per second times the length of one wavelength should give you the distance traveled per second, so that’s, effectively, the wave’s speed).

Now that we’ve expressed the frequency in radians per second, we can also express the wavelength in radians per unit distance too. That’s what the wavenumber does: think of it as the spatial frequency of the wave. We denote the wavenumber by k, and write: k = 2π/λ. [Just do a numerical example when you have difficulty following. For example, if you’d assume the wavelength is 5 units distance (i.e. 5 meter) – that’s a typical VHF radio frequency: ν = (3×108 m/s)/(5 m) = 0.6×108 Hz = 60 MHz – then that would correspond to (2π radians)/(5 m) ≈ 1.2566 radians per meter. Of course, we can also express the wave number in oscillations per unit distance. In that case, we’d have to divide k by 2π, because one cycle corresponds to 2π radians. So we get the reciprocal of the wavelength: 1/λ. In our example, 1/λ is, of course, 1/5 = 0.2, so that’s a fifth of a full cycle. You can also think of it as the number of waves (or wavelengths) per meter: if the wavelength is λ, then one can fit 1/λ waves in a meter.

Now, from the ω = 2πν, c = λν and k = 2π/λ relations, it’s obvious that k = 2π/λ = 2π/(c/ν) = (2πν)/c = ω/c. To sum it all up, frequencies and wavelengths, in time and in space, are all related through the speed of propagation of the wave c. More specifically, they’re related as follows:

c = λν = ω/k

From that, it’s easy to see that k = ω/c, which we’ll use in a moment. Now, it’s obvious that the periodicity of the wave implies that we can find the same phase by going one oscillation (or a multiple number of oscillations back or forward in time, or in space. In fact, we can also find the same phase by letting both time and space vary. However, if we want to do that, it should be obvious that we should either (a) go forward in space and back in time or, alternatively, (b) go back in space and forward in time. In other words, if we want to get the same phase, then time and space sort of substitute for each other. Let me quote Feynman on this: “This is easily seen by considering the mathematical behavior of a(t−r/c). Evidently, if we add a little time Δt, we get the same value for a(t−r/c) as we would have if we had subtracted a little distance: Δr = −cΔt.” The variable a stands for the acceleration of an electric charge here, causing an electromagnetic wave, but the same logic is valid for the phase, with a minor twist though: we’re talking a nice periodic function here, and so we need to put the angular frequency in front. Hence, the rate of change of the phase in respect to time is measured by the angular frequency ω. In short, we write:

θ = ω(t–x/c) = ωt–kx

Hence, we can re-write the wavefunction, in terms of its phase, as follows:

φ(θ) = φ[θ(x, t)] = φ[ωt–kx]

Note that, if the wave would be traveling in the ‘other’ direction (i.e. in the negative x-direction), we’d write φ(θ) = φ[kx+ωt]. Time travels in one direction only, of course, but so one minus sign has to be there because of the logic involved in adding time and subtracting distance. You can work out an example (with a sine or cosine wave, for example) for yourself.

So what, you’ll say? Well… Nothing. I just hope you agree that all of this isn’t rocket science: it’s just high-school math. But so it shows you what that stopwatch really is and, hence, I – but who am I? – would have put at least one or two footnotes on this in a text like Feynman’s QED.

Now, let me make a much longer and more serious digression:

Digression 1: on relativity and spacetime

As you can see from the argument (or phase) of that wave function φ(θ) = φ[θ(x, t)] = φ[ωt–kx] = φ[–k(x–ct)], any wave equation establishes a deep relation between the wave itself (i.e. the ‘thing’ we’re describing) and space and time. In fact, that’s what the whole wave equation is all about! So let me say a few things more about that.

Because you know a thing or two about physics, you may ask: when we’re talking time, whose time are we talking about? Indeed, if we’re talking photons going from A to B, these photons will be traveling at or near the speed of light and, hence, their clock, as seen from our (inertial) frame of reference, doesn’t move. Likewise, according to the photon, our clock seems to be standing still.

Let me put the issue to bed immediately: we’re looking at things from our point of view. Hence, we’re obviously using our clock, not theirs. Having said that, the analysis is actually fully consistent with relativity theory. Why? Well… What do you expect? If it wasn’t, the analysis would obviously not be valid. 🙂 To illustrate that it’s consistent with relativity theory, I can mention, for example, that the (probability) amplitude for a photon to travel from point A to B depends on the spacetime interval, which is invariant. Hence, A and B are four-dimensional points in spacetime, involving both spatial as well as time coordinates: A = (xA, yA, zA, tA) and B = (xB, yB, zB, tB). And so the ‘distance’ – as measured through the spacetime interval – is invariant.

Now, having said that, we should draw some attention to the intimate relationship between space and time which, let me remind you, results from the absoluteness of the speed of light. Indeed, one will always measure the speed of light c as being equal to 299,792,458 m/s, always and everywhere. It does not depend on your reference frame (inertial or moving). That’s why the constant c anchors all laws in physics, and why we can write what we write above, i.e. include both distance (x) as well as time (t) in the wave function φ = φ(x, t) = φ[ωt–kx] = φ[–k(x–ct)]. The k and ω are related through the ω/k = c relationship: the speed of light links the frequency in time (ν = ω/2π = 1/T) with the frequency in space (i.e. the wavenumber or spatial frequency k). There is only degree of freedom here: the frequency—in space or in time, it doesn’t matter: ν and ω are not independent. [As noted above, the relationship between the frequency in time and in space is not so obvious for electrons, or for matter waves in general: for those matter-waves, we need to distinguish group and phase velocity, and so we don’t have a unique frequency.]

Let me make another small digression within the digression here. Thinking about travel at the speed of light invariably leads to paradoxes. In previous posts, I explained the mechanism of light emission: a photon is emitted – one photon only – when an electron jumps back to its ground state after being excited. Hence, we may imagine a photon as a transient electromagnetic wave–something like what’s pictured below. Now, the decay time of this transient oscillation (τ) is measured in nanoseconds, i.e. billionths of a second (1 ns = 1×10–9 s): the decay time for sodium light, for example, is some 30 ns only.

However, because of the tremendous speed of light, that still makes for a wavetrain that’s like ten meter long, at least (30×10–9 s times 3×108 m/s is nine meter, but you should note that the decay time measures the time for the oscillation to die out by a factor 1/e, so the oscillation itself lasts longer than that). Those nine or ten meters cover like 16 to 17 million oscillations (the wavelength of sodium light is about 600 nm and, hence, 10 meter fits almost 17 million oscillations indeed). Now, how can we reconcile the image of a photon as a ten-meter long wavetrain with the image of a photon as a point particle?

The answer to that question is paradoxical: from our perspective, anything traveling at the speed of light – including this nine or ten meter ‘long’ photon – will have zero length because of the relativistic length contraction effect. Length contraction? Yes. I’ll let you look it up, because… Well… It’s not easy to grasp. Indeed, from the three measurable effects on objects moving at relativistic speeds – i.e. (1) an increase of the mass (the energy needed to further accelerate particles in particle accelerators increases dramatically at speeds nearer to c), (2) time dilation, i.e. a slowing down of the (internal) clock (because of their relativistic speeds when entering the Earth’s atmosphere, the measured half-life of muons is five times that when at rest), and (3) length contraction – length contraction is probably the most paradoxical of all.

Let me end this digression with yet another short note. I said that one will always measure the speed of light c as being equal to 299,792,458 m/s, always and everywhere and, hence, that it does not depend on your reference frame (inertial or moving). Well… That’s true and not true at the same time. I actually need to nuance that statement a bit in light of what follows: an individual photon does have an amplitude to travel faster or slower than c, and when discussing matter waves (such as the wavefunction that’s associated with an electron), we can have phase velocities that are faster than light! However, when calculating those amplitudes, c is a constant.

That doesn’t make sense, you’ll say. Well… What can I say? That’s how it is unfortunately. I need to move on and, hence, I’ll end this digression and get back to the main story line. Part I explained what probability amplitudes are—or at least tried to do so. Now it’s time for part II: the building blocks of all of quantum electrodynamics (QED).

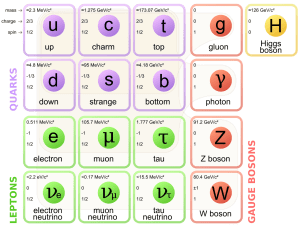

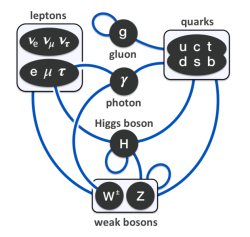

II. The building blocks: P(A to B), E(A to B) and j

The three basic ‘events’ (and, hence, amplitudes) in QED are the following:

1. P(A to B)

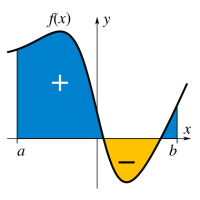

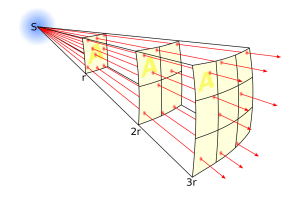

P(A to B) is the (probability) amplitude for a photon to travel from point A to B. However, I should immediately note that A and B are points in spacetime. Therefore, we associate them not only with some specific (x, y, z) position in space, but also with a some specific time t. Now, quantum-mechanical theory gives us an easy formula for P(A to B): it depends on the so-called (spacetime) interval between the two points A and B, i.e. I = Δr2 – Δt2 = (x2–x1)2+(y2–y1)2+(z2–z1)2 – (t2–t1)2. The point to note is that the spacetime interval takes both the distance in space as well as the ‘distance’ in time into account. As I mentioned already, this spacetime interval does not depend on our reference frame and, hence, it’s invariant (as long as we’re talking reference frames that move with constant speed relative to each other). Also note that we should measure time and distance in equivalent units when using that Δr2 – Δt2 formula for I. So we either measure distance in light-seconds or, else, we measure time in units that correspond to the time that’s needed for light to travel one meter. If no equivalent units are adopted, the formula is I = Δr2 – c·Δt2.

Now, in quantum theory, anything is possible and, hence, not only do we allow for crooked paths, but we also allow for the difference in time to differ from the time you’d expect a photon to need to travel along some curve (whose length we’ll denote by l), i.e. l/c. Hence, our photon may actually travel slower or faster than the speed of light c! There is one lucky break, however, that makes all come out alright: it’s easy to show that the amplitudes associated with the odd paths and strange timings generally cancel each other out. [That’s what the QED booklet shows.] Hence, what remains, are the paths that are equal or, importantly, those that very near to the so-called ‘light-like’ intervals in spacetime only. The net result is that light – even one single photon – effectively uses a (very) small core of space as it travels, as evidenced by the fact that even one single photon interferes with itself when traveling through a slit or a small hole!

[If you now wonder what it means for a photon to interfere for itself, let me just give you the easy explanation: it may change its path. We assume it was traveling in a straight line – if only because it left the source at some point in time and then arrived at the slit obviously – but so it no longer travels in a straight line after going through the slit. So that’s what we mean here.]

2. E(A to B)

E(A to B) is the (probability) amplitude for an electron to travel from point A to B. The formula for E(A to B) is much more complicated, and it’s the one I want to discuss somewhat more in detail in this post. It depends on some complex number j (see the next remark) and some real number n.

3. j

Finally, an electron could emit or absorb a photon, and the amplitude associated with this event is denoted by j, for junction number. It’s the same number j as the one mentioned when discussing E(A to B) above.

Now, this junction number is often referred to as the coupling constant or the fine-structure constant. However, the truth is, as I pointed out in my previous post, that these numbers are related, but they are not quite the same: α is the square of j, so we have α = j2. There is also one more, related, number: the gauge parameter, which is denoted by g (despite the g notation, it has nothing to do with gravitation). The value of g is the square root of 4πε0α, so g2 = 4πε0α. I’ll come back to this. Let me first make an awfully long digression on the fine-structure constant. It will be awfully long. So long that it’s actually part of the ‘core’ of this post actually.

Digression 2: on the fine-structure constant, Planck units and the Bohr radius

The value for j is approximately –0.08542454.

How do we know that?

The easy answer to that question is: physicists measured it. In fact, they usually publish the measured value as the square root of the (absolute value) of j, which is that fine-structure constant α. Its value is published (and updated) by the US National Institute on Standards and Technology. To be precise, the currently accepted value of α is 7.29735257×10−3. In case you doubt, just check that square root:

j = –0.08542454 ≈ –√0.00729735257 = –√α

As noted in Feynman’s (or Leighton’s) QED, older and/or more popular books will usually mention 1/α as the ‘magical’ number, so the ‘special’ number you may have seen is the inverse fine-structure constant, which is about 137, but not quite:

1/α = 137.035999074 ± 0.000000044

I am adding the standard uncertainty just to give you an idea of how precise these measurements are. 🙂 About 0.32 parts per billion (just divide the 137.035999074 number by the uncertainty). So that‘s the number that excites popular writers, including Leighton. Indeed, as Leighton puts it:

“Where does this number come from? Nobody knows. It’s one of the greatest damn mysteries of physics: a magic number that comes to us with no understanding by man. You might say the “hand of God” wrote that number, and “we don’t know how He pushed his pencil.” We know what kind of a dance to do experimentally to measure this number very accurately, but we don’t know what kind of dance to do on the computer to make this number come out, without putting it in secretly!”

Is it Leighton, or did Feynman really say this? Not sure. While the fine-structure constant is a very special number, it’s not the only ‘special’ number. In fact, we derive it from other ‘magical’ numbers. To be specific, I’ll show you how we derive it from the fundamental properties – as measured, of course – of the electron. So, in fact, I should say that we do know how to make this number come out, which makes me doubt whether Feynman really said what Leighton said he said. 🙂

So we can derive α from some other numbers. That brings me to the more complicated answer to the question as to what the value of j really is: j‘s value is the electron charge expressed in Planck units, which I’ll denote by –eP:

j = –eP

[You may want to reflect on this, and quickly verify on the Web. The Planck unit of electric charge, expressed in Coulomb, is about 1.87555×10–18 C. If you multiply that j = –eP, so with –0.08542454, you get the right answer: the electron charge is about –0.160217×10–18 C.]

Now that is strange.

Why? Well… For starters, when doing all those quantum-mechanical calculations, we like to think of j as a dimensionless number: a coupling constant. But so here we do have a dimension: electric charge.

Let’s look at the basics. If j is –√α, and it’s also equal to –eP, then the fine-structure constant must also be equal to the square of the electron charge eP, so we can write:

α = eP2

You’ll say: yes, so what? Well… I am pretty sure that, if you’ve ever seen a formula for α, it’s surely not this simple j = –eP or α = eP2 formula. What you’ve seen, most likely, is one or more of the following expressions below :

That’s a pretty impressive collection of physical constants, isn’t it? 🙂 They’re all different but, somehow, when we combine them in one or the other ratio (we have not less than five different expressions here (each identity is a separate expression), and I could give you a few more!), we get the very same number: α. Now that is what I call strange. Truly strange. Incomprehensibly weird!

You’ll say… Well… Those constants must all be related… Of course! That’s exactly the point I am making here. They are, but look how different they are: me measures mass, re measures distance, e is a charge, and so these are all very different numbers with very different dimensions. Yet, somehow, they are all related through this α number. Frankly, I do not know of any other expression that better illustrates some kind of underlying unity in Nature than the one with those five identities above.

Let’s have a closer look at those constants. You know most of them already. The only constants you may not have seen before are μ0, RK and, perhaps, re as well as me . However, these can easily be defined as some easy function of the constants that you did see before, so let me quickly do that:

- The μ0 constant is the so-called magnetic constant. It’s something similar as ε0 and it’s referred to as the magnetic permeability of the vacuum. So it’s just like the (electric) permittivity of the vacuum (i.e. the electric constant ε0) and the only reason why this blog hasn’t mentioned this constant before is because I haven’t really discussed magnetic fields so far. I only talked about the electric field vector. In any case, you know that the electric and magnetic force are part and parcel of the same phenomenon (i.e. the electromagnetic interaction between charged particles) and, hence, they are closely related. To be precise, μ0ε0 = 1/c2 = c–2. So that shows the first and second expression for α are, effectively, fully equivalent. [Just in case you’d doubt that μ0ε0 = 1/c2, let me give you the values: μ0 = 4π·10–7 N/A2, and ε0 = (1/4π·c2)·107 C2/N·m2. Just plug them in, and you’ll see it’s bang on. Moreover, note that the ampere (A) unit is equal to the coulomb per second unit (C/s), so even the units come out alright. 🙂 Of course they do!]

- The ke constant is the Coulomb constant and, from its definition ke = 1/4πε0, it’s easy to see how those two expressions are, in turn, equivalent with the third expression for α.

- The RK constant is the so-called von Klitzing constant. Huh? Yes. I know. I am pretty sure you’ve never ever heard of that one before. Don’t worry about it. It’s, quite simply, equal to RK = h/e2. Hence, substituting (and don’t forget that h = 2πħ) will demonstrate the equivalence of the fourth expression for α.

- Finally, the re factor is the classical electron radius, which is usually written as a function of me, i.e. the electron mass: re = e2/4πε0mec2. Also note that this also implies that reme = e2/4πε0c2. In words: the product of the electron mass and the electron radius is equal to some constant involving the electron (e), the electric constant (ε0), and c (the speed of light).

I am sure you’re under some kind of ‘formula shock’ now. But you should just take a deep breath and read on. The point to note is that all these very different things are all related through α.

So, again, what is that α really? Well… A strange number indeed. It’s dimensionless (so we don’t measure in kg, m/s, eV·s or whatever) and it pops up everywhere. [Of course, you’ll say: “What’s everywhere? This is the first time I‘ve heard of it!” :-)]

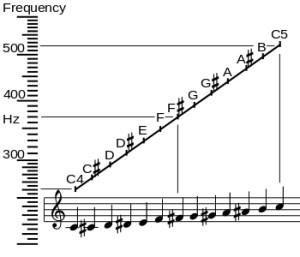

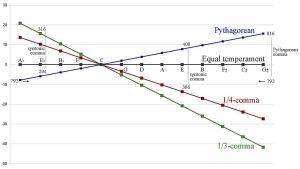

Well… Let me start by explaining the term itself. The fine structure in the name refers to the splitting of the spectral lines of atoms. That’s a very fine structure indeed. 🙂 We also have a so-called hyperfine structure. Both are illustrated below for the hydrogen atom. The numbers n, J, I, and F are quantum numbers used in the quantum-mechanical explanation of the emission spectrum, which is also depicted below, but note that the illustration gives you the so-called Balmer series only, i.e. the colors in the visible light spectrum (there are many more ‘colors’ in the high-energy ultraviolet and the low-energy infrared range).

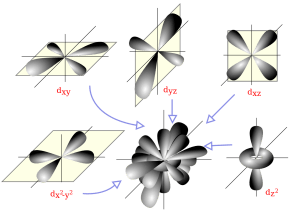

To be precise: (1) n is the principal quantum number: here it takes the values 1 or 2, and we could say these are the principal shells; (2) the S, P, D,… orbitals (which are usually written in lower case: s, p, d, f, g, h and i) correspond to the (orbital) angular momentum quantum number l = 0, 1, 2,…, so we could say it’s the subshell; (3) the J values correspond to the so-called magnetic quantum number m, which goes from –l to +l; (4) the fourth quantum number is the spin angular momentum s. I’ve copied another diagram below so you see how it works, more or less, that is.

Now, our fine-structure constant is related to these quantum numbers. How exactly is a bit of a long story, and so I’ll just copy Wikipedia’s summary on this: ” The gross structure of line spectra is the line spectra predicted by the quantum mechanics of non-relativistic electrons with no spin. For a hydrogenic atom, the gross structure energy levels only depend on the principal quantum number n. However, a more accurate model takes into account relativistic and spin effects, which break the degeneracy of the the energy levels and split the spectral lines. The scale of the fine structure splitting relative to the gross structure energies is on the order of (Zα)2, where Z is the atomic number and α is the fine-structure constant.” There you go. You’ll say: so what? Well… Nothing. If you aren’t amazed by that, you should stop reading this.

It is an ‘amazing’ number, indeed, and, hence, it does quality for being “one of the greatest damn mysteries of physics”, as Feynman and/or Leighton put it. Having said that, I would not go as far as to write that it’s “a magic number that comes to us with no understanding by man.” In fact, I think Feynman/Leighton could have done a much better job when explaining what it’s all about. So, yes, I hope to do better than Leighton here and, as he’s still alive, I actually hope he reads this. 🙂

The point is: α is not the only weird number. What’s particular about it, as a physical constant, is that it’s dimensionless, because it relates a number of other physical constants in such a way that the units fall away. Having said that, the Planck or Boltzmann constant are at least as weird.

So… What is this all about? Well… You’ve probably heard about the so-called fine-tuning problem in physics and, if you’re like me, your first reaction will be to associate fine-tuning with fine-structure. However, the two terms have nothing in common, except for four letters. 🙂 OK. Well… I am exaggerating here. The two terms are actually related, to some extent at least, but let me explain how.

The term fine-tuning refers to the fact that all the parameters or constants in the so-called Standard Model of physics are, indeed, all related to each other in the way they are. We can’t sort of just turn the knob of one and change it, because everything falls apart then. So, in essence, the fine-tuning problem in physics is more like a philosophical question: why is the value of all these physical constants and parameters exactly what it is? So it’s like asking: could we change some of the ‘constants’ and still end up with the world we’re living in? Or, if it would be some different world, how would it look like? What if c was some other number? What if ke or ε0 was some other number? In short, and in light of those expressions for α, we may rephrase the question as: why is α what is is?

Of course, that’s a question one shouldn’t try to answer before answering some other, more fundamental, question: how many degrees of freedom are there really? Indeed, we just saw that ke and ε0 are intimately related through some equation, and other constants and parameters are related too. So the question is like: what are the ‘dependent’ and the ‘independent’ variables in this so-called Standard Model?

There is no easy answer to that question. In fact, one of the reasons why I find physics so fascinating is that one cannot easily answer such questions. There are the obvious relationships, of course. For example, the ke = 1/4πε0 relationship, and the context in which they are used (Coulomb’s Law) does, indeed, strongly suggest that both constants are actually part and parcel of the same thing. Identical, I’d say. Likewise, the μ0ε0 = 1/c2 relation also suggests there’s only one degree of freedom here, just like there’s only one degree of freedom in that ω/k = c relationship (if we set a value for ω, we have k, and vice versa). But… Well… I am not quite sure how to phrase this, but… What physical constants could be ‘variables’ indeed?

It’s pretty obvious that the various formulas for α cannot answer that question: you could stare at them for days and weeks and months and years really, but I’d suggest you use your time to read more of Feynman’s real Lectures instead. 🙂 One point that may help to come to terms with this question – to some extent, at least – is what I casually mentioned above already: the fine-structure constant is equal to the square of the electron charge expressed in Planck units: α = eP2.

Now, that’s very remarkable because Planck units are some kind of ‘natural units’ indeed (for the detail, see my previous post: among other things, it explains what these Planck units really are) and, therefore, it is quite tempting to think that we’ve actually got only one degree of freedom here: α itself. All the rest should follow from it.

[…]

It should… But… Does it?

The answer is: yes and no. To be frank, it’s more no than yes because, as I noted a couple of times already, the fine-structure constant relates a lot of stuff but it’s surely not the only significant number in the Universe. For starters, I said that our E(A to B) formula has two ‘variables’:

- We have that complex number j, which, as mentioned, is equal to the electron charge expressed in Planck units. [In case you wonder why –eP ≈ –0.08542455 is said to be an amplitude, i.e. a complex number or an ‘arrow’… Well… Complex numbers include the real numbers and, hence, –0.08542455 is both real and complex. When combining ‘arrows’ or, to be precise, when multiplying some complex number with –0.08542455, we will (a) shrink the original arrow to about 8.5% of its original value (8.542455% to be precise) and (b) rotate it over an angle of plus or minus 180 degrees. In other words, we’ll reverse its direction. Hence, using Euler’s notation for complex numbers, we can write: –1 = eiπ = e–iπ and, hence, –0.085 = 0.085·eiπ = 0.085·e–iπ. So, in short, yes, j is a complex number, or an ‘arrow’, if you prefer that term.]

- We also have some some real number n in the E(A to B) formula. So what’s the n? Well… Believe it or not, it’s the electron mass! Isn’t that amazing?

You’ll say: “Well… Hmm… I suppose so.” But then you may – and actually should – also wonder: the electron mass? In what units? Planck units again? And are we talking relativistic mass (i.e. its total mass, including the equivalent mass of its kinetic energy) or its rest mass only? And we were talking α here, so can we relate it to α too, just like the electron charge?

These are all very good questions. Let’s start with the second one. We’re talking rather slow-moving electrons here, so the relativistic mass (m) and its rest mass (m0) is more or less the same. Indeed, the Lorentz factor γ in the m = γm0 equation is very close to 1 for electrons moving at their typical speed. So… Well… That question doesn’t matter very much. Really? Yes. OK. Because you’re doubting, I’ll quickly show it to you. What is their ‘typical’ speed?

We know we shouldn’t attach too much importance to the concept of an electron in orbit around some nucleus (we know it’s not like some planet orbiting around some star) and, hence, to the concept of speed or velocity (velocity is speed with direction) when discussing an electron in an atom. The concept of momentum (i.e. velocity combined with mass or energy) is much more relevant. There’s a very easy mathematical relationship that gives us some clue here: the Uncertainty Principle. In fact, we’ll use the Uncertainty Principle to relate the momentum of an electron (p) to the so-called Bohr radius r (think of it as the size of a hydrogen atom) as follows: p ≈ ħ/r. [I’ll come back on this in a moment, and show you why this makes sense.]

Now we also know its kinetic energy (K.E.) is mv2/2, which we can write as p2/2m. Substituting our p ≈ ħ/r conjecture, we get K.E. = mv2/2 = ħ2/2mr2. This is equivalent to m2v2 = ħ2/r2 (just multiply both sides with m). From that, we get v = ħ/mr. Now, one of the many relations we can derive from the formulas for the fine-structure constant is re = α2r. [I haven’t showed you that yet, but I will shortly. It’s a really amazing expression. However, as for now, just accept it as a simple formula for interim use in this digression.] Hence, r = re/α2. The re factor in this expression is the so-called classical electron radius. So we can now write v = ħα2/mre. Let’s now throw c in: v/c = α2ħ/mcre. However, from that fifth expression for α, we know that ħ/mcre = α, so we get v/c = α. We have another amazing result here: the v/c ratio for an electron (i.e. its speed expressed as a fraction of the speed of light) is equal to that fine-structure constant α. So that’s about 1/137, so that’s less than 1% of the speed of light. Now… I’ll leave it to you to calculate the Lorentz factor γ but… Well… It’s obvious that it will be very close to 1. 🙂 Hence, the electron’s speed – however we want to visualize that – doesn’t matter much indeed, so we should not worry about relativistic corrections in the formulas.

Let’s now look at the question in regard to the Planck units. If you know nothing at all about them, I would advise you to read what I wrote about them in my previous post. Let me just note we get those Planck units by equating not less than five fundamental physical constants to 1, notably (1) the speed of light, (2) Planck’s (reduced) constant, (3) Boltzmann’s constant, (4) Coulomb’s constant and (5) Newton’s constant (i.e. the gravitational constant). Hence, we have a set of five equations here (c = ħ = kB = ke = G = 1), and so we can solve that to get the five Planck units, i.e. the Planck length unit, the Planck time unit, the Planck mass unit, the Planck energy unit, the Planck charge unit and, finally (oft forgotten), the Planck temperature unit. Of course, you should note that all mass and energy units are directly related because of the mass-energy equivalence relation E = mc2, which simplifies to E = m if c is equated to 1. [I could also say something about the relation between temperature and (kinetic) energy, but I won’t, as it would only further confuse you.]

Now, you may or may not remember that the Planck time and length units are unimaginably small, but that the Planck mass unit is actually quite sizable—at the atomic scale, that is. Indeed, the Planck mass is something huge, like the mass of an eyebrow hair, or a flea egg. Is that huge? Yes. Because if you’d want to pack it in a Planck-sized particle, it would make for a tiny black hole. 🙂 No kidding. That’s the physical significance of the Planck mass and the Planck length and, yes, it’s weird. 🙂

Let me give you some values. First, the Planck mass itself: it’s about 2.1765×10−8 kg. Again, if you think that’s tiny, think again. From the E = mc2 equivalence relationship, we get that this is equivalent to 2 giga-joule, approximately. Just to give an idea, that’s like the monthly electricity consumption of an average American family. So that’s huge indeed! 🙂 [Many people think that nuclear energy involves the conversion of mass into energy, but the story is actually more complicated than that. In any case… I need to move on.]

Let me now give you the electron mass expressed in the Planck mass unit:

- Measured in our old-fashioned super-sized SI kilogram unit, the electron mass is me = 9.1×10–31 kg.

- The Planck mass is mP = 2.1765×10−8 kg.

- Hence, the electron mass expressed in Planck units is meP = me/mP = (9.1×10–31 kg)/(2.1765×10−8 kg) = 4.181×10−23.

We can, once again, write that as some function of the fine-structure constant. More specifically, we can write:

meP = α/reP = α/α2rP = 1/αrP

So… Well… Yes: yet another amazing formula involving α.

In this formula, we have reP and rP, which are the (classical) electron radius and the Bohr radius expressed in Planck (length) units respectively. So you can see what’s going on here: we have all kinds of numbers here expressed in Planck units: a charge, a radius, a mass,… And we can relate all of them to the fine-structure constant.

Why? Who knows? I don’t. As Leighton puts it: that’s just the way “God pushed His pencil.” 🙂

Note that the beauty of natural units ensures that we get the same number for the (equivalent) energy of an electron. Indeed, from the E = mc2 relation, we know the mass of an electron can also be written as 0.511 MeV/c2. Hence, the equivalent energy is 0.511 MeV (so that’s, quite simply, the same number but without the 1/c2 factor). Now, the Planck energy EP (in eV) is 1.22×1028 eV, so we get EeP = Ee/EP = (0.511×106 eV)/(1.22×1028 eV) = 4.181×10−23. So it’s exactly the same as the electron mass expressed in Planck units. Isn’t that nice? 🙂

Now, are all these numbers dimensionless, just like α? The answer to that question is complicated. Yes, and… Well… No:

- Yes. They’re dimensionless because they measure something in natural units, i.e. Planck units, and, hence, that’s some kind of relative measure indeed so… Well… Yes, dimensionless.

- No. They’re not dimensionless because they do measure something, like a charge, a length, or a mass, and when you chose some kind of relative measure, you still need to define some gauge, i.e. some kind of standard measure. So there’s some ‘dimension’ involved there.

So what’s the final answer? Well… The Planck units are not dimensionless. All we can say is that they are closely related, physically. I should also add that we’ll use the electron charge and mass (expressed in Planck units) in our amplitude calculations as a simple (dimensionless) number between zero and one. So the correct answer to the question as to whether these numbers have any dimension is: expressing some quantities in Planck units sort of normalizes them, so we can use them directly in dimensionless calculations, like when we multiply and add amplitudes.

Hmm… Well… I can imagine you’re not very happy with this answer but it’s the best I can do. Sorry. I’ll let you further ponder that question. I need to move on.

Note that that 4.181×10−23 is still a very small number (23 zeroes after the decimal point!), even if it’s like 46 million times larger than the electron mass measured in our conventional SI unit (i.e. 9.1×10–31 kg). Does such small number make any sense? The answer is: yes, it does. When we’ll finally start discussing that E(A to B) formula (I’ll give it to you in a moment), you’ll see that a very small number for n makes a lot of sense.

Before diving into it all, let’s first see if that formula for that alpha, that fine-structure constant, still makes sense with me expressed in Planck units. Just to make sure. 🙂 To do that, we need to use the fifth (last) expression for a, i.e. the one with re in it. Now, in my previous post, I also gave some formula for re: re = e2/4πε0mec2, which we can re-write as reme = e2/4πε0c2. If we substitute that expression for reme in the formula for α, we can calculate α from the electron charge, which indicates both the electron radius and its mass are not some random God-given variable, or “some magic number that comes to us with no understanding by man“, as Feynman – well… Leighton, I guess – puts it. No. They are magic numbers alright, one related to another through the equally ‘magic’ number α, but so I do feel we actually can create some understanding here.

At this point, I’ll digress once again, and insert some quick back-of-the-envelope argument from Feynman’s very serious Caltech Lectures on Physics, in which, as part of the introduction to quantum mechanics, he calculates the so-called Bohr radius from Planck’s constant h. Let me quickly explain: the Bohr radius is, roughly speaking, the size of the simplest atom, i.e. an atom with one electron (so that’s hydrogen really). So it’s not the classical electron radius re. However, both are also related to that ‘magical number’ α. To be precise, if we write the Bohr radius as r, then re = α2r ≈ 0.000053… times r, which we can re-write as:

α = √(re /r) = (re /r)1/2

So that’s yet another amazing formula involving the fine-structure constant. In fact, it’s the formula I used as an ‘interim’ expression to calculate the relative speed of electrons. I just used it without any explanation there, but I am coming back to it here. Alpha again…

Just think about it for a while. In case you’d still doubt the magic of that number, let me write what we’ve discovered so far:

(1) α is the square of the electron charge expressed in Planck units: α = eP2.

(2) α is the square root of the ratio of (a) the classical electron radius and (b) the Bohr radius: α = √(re /r). You’ll see this more often written as re = α2r. Also note that this is an equation that does not depend on the units, in contrast to equation 1 (above), and 4 and 5 (below), which require you to switch to Planck units. It’s the square of a ratio and, hence, the units don’t matter. They fall away.

(3) α is the (relative) speed of an electron: α = v/c. [The relative speed is the speed as measured against the speed of light. Note that the ‘natural’ unit of speed in the Planck system of units is equal to c. Indeed, if you divide one Planck length by one Planck time unit, you get (1.616×10−35 m)/(5.391×10−44 s) = c m/s. However, this is another equation, just like (2), that does not depend on the units: we can express v and c in whatever unit we want, as long we’re consistent and express both in the same units.]

(4) Finally – I’ll show you in a moment – α is also equal to the product of (a) the electron mass (which I’ll simply write as me here) and (b) the classical electron radius re (if both are expressed in Planck units): α = me·re. Now I think that’s, perhaps, the most amazing of all of the expressions for α. If you don’t think that’s amazing, I’d really suggest you stop trying to study physics. 🙂

Note that, from (2) and (4), we find that:

(5) The electron mass (in Planck units) is equal me = α/re = α/α2r = 1/αr. So that gives us an expression, using α once again, for the electron mass as a function of the Bohr radius r expressed in Planck units.

Finally, we can also substitute (1) in (5) to get:

(6) The electron mass (in Planck units) is equal to me = α/re = eP2/re. Using the Bohr radius, we get me = 1/αr = 1/eP2r.

So… As you can see, this fine-structure constant really links ALL of the fundamental properties of the electron: its charge, its radius, its distance to the nucleus (i.e. the Bohr radius), its velocity, its mass (and, hence, its energy),… In short,

IT IS ALL IN ALPHA!

Now that should answer the question in regard to the degrees of freedom we have here, doesn’t it? It looks like we’ve got only one degree of freedom here. Indeed, if we’ve got some value for α, then we’ve have the electron charge, and from the electron charge, we can calculate the Bohr radius r (as I will show below), and if we have r, we have me and re. And then we can also calculate v, which gives us its momentum (mv) and its kinetic energy (mv2/2). In short,

ALPHA GIVES US EVERYTHING!

Isn’t that amazing? Hmm… You should reserve your judgment as for now, and carefully go over all of the formulas above and verify my statement. If you do that, you’ll probably struggle to find the Bohr radius from the charge (i.e. from α). So let me show you how you do that, because it will also show you why you should, indeed, reserve your judgment. In other words, I’ll show you why alpha does NOT give us everything! The argument below will, finally, prove some of the formulas that I didn’t prove above. Let’s go for it:

1. If we assume that (a) an electron takes some space – which I’ll denote by r 🙂 – and (b) that it has some momentum p because of its mass m and its velocity v, then the ΔxΔp = ħ relation (i.e. the Uncertainty Principle in its roughest form) suggests that the order of magnitude of r and p should be related in the very same way. Hence, let’s just boldly write r ≈ ħ/p and see what we can do with that. So we equate Δx with r and Δp with p. As Feynman notes, this is really more like a ‘dimensional analysis’ (he obviously means something very ‘rough’ with that) and so we don’t care about factors like 2 or 1/2. [Indeed, note that the more precise formulation of the Uncertainty Principle is σxσp ≥ ħ/2.] In fact, we didn’t even bother to define r very rigorously. We just don’t care about precise statements at this point. We’re only concerned about orders of magnitude. [If you’re appalled by the rather rude approach, I am sorry for that, but just try to go along with it.]

2. From our discussions on energy, we know that the kinetic energy is mv2/2, which we can write as p2/2m so we get rid of the velocity factor. [Why? Because we can’t really imagine what it is anyway. As I said a couple of times already, we shouldn’t think of electrons as planets orbiting around some star. That model doesn’t work.] So… What’s next? Well… Substituting our p ≈ ħ/r conjecture, we get K.E. = ħ2/2mr2. So that’s a formula for the kinetic energy. Next is potential.

3. Unfortunately, the discussion on potential energy is a bit more complicated. You’ll probably remember that we had an easy and very comprehensible formula for the energy that’s needed (i.e. the work that needs to be done) to bring two charges together from a large distance (i.e. infinity). Indeed, we derived that formula directly from Coulomb’s Law (and Newton’s law of force) and it’s U = q1q2/4πε0r12. [If you think I am going too fast, sorry, please check for yourself by reading my other posts.] Now, we’re actually talking about the size of an atom here in my previous post, so one charge is the proton (+e) and the other is the electron (–e), so the potential energy is U = P.E. = –e2/4πε0r, with r the ‘distance’ between the proton and the electron—so that’s the Bohr radius we’re looking for!

[In case you’re struggling a bit with those minus signs when talking potential energy – I am not ashamed to admit I did! – let me quickly help you here. It has to do with our reference point: the reference point for measuring potential energy is at infinity, and it’s zero there (that’s just our convention). Now, to separate the proton and the electron, we’d have to do quite a lot of work. To use an analogy: imagine we’re somewhere deep down in a cave, and we have to climb back to the zero level. You’ll agree that’s likely to involve some sweat, don’t you? Hence, the potential energy associated with us being down in the cave is negative. Likewise, if we write the potential energy between the proton and the electron as U(r), and the potential energy at the reference point as U(∞) = 0, then the work to be done to separate the charges, i.e. the potential difference U(∞) – U(r), will be positive. So U(∞) – U(r) = 0 – U(r) > 0 and, hence, U(r) < 0. If you still don’t ‘get’ this, think of the electron being in some (potential) well, i.e. below the zero level, and so it’s potential energy is less than zero. Huh? Sorry. I have to move on. :-)]

4. We can now write the total energy (which I’ll denote by E, but don’t confuse it with the electric field vector!) as

E = K.E. + P.E. = ħ2/2mr2 – e2/4πε0r

Now, the electron (whatever it is) is, obviously, in some kind of equilibrium state. Why is that obvious? Well… Otherwise our hydrogen atom wouldn’t or couldn’t exist. 🙂 Hence, it’s in some kind of energy ‘well’ indeed, at the bottom. Such equilibrium point ‘at the bottom’ is characterized by its derivative (in respect to whatever variable) being equal to zero. Now, the only ‘variable’ here is r (all the other symbols are physical constants), so we have to solve for dE/dr = 0. Writing it all out yields:

dE/dr = –ħ2/mr3 + e2/4πε0r2 = 0 ⇔ r = 4πε0ħ2/me2

You’ll say: so what? Well… We’ve got a nice formula for the Bohr radius here, and we got it in no time! 🙂 But the analysis was rough, so let’s check if it’s any good by putting the values in:

r = 4πε0h2/me2

= [(1/(9×109) C2/N·m2)·(1.055×10–34 J·s)2]/[(9.1×10–31 kg)·(1.6×10–19 C)2]

= 53×10–12 m = 53 pico-meter (pm)

So what? Well… Double-check it on the Internet: the Bohr radius is, effectively, about 53 trillionths of a meter indeed! So we’re right on the spot!

[In case you wonder about the units, note that mass is a measure of inertia: one kg is the mass of an object which, subject to a force of 1 newton, will accelerate at the rate of 1 m/s per second. Hence, we write F = m·a, which is equivalent to m = F/a. Hence, the kg, as a unit, is equivalent to 1 N/(m/s2). If you make this substitution, we get r in the unit we want to see: [(C2/N·m2)·(N2·m2·s2)/[(N·s2/m)·C2] = m.]

Moreover, if we take that value for r and put it in the (total) energy formula above, we’d find that the energy of the electron is –13.6 eV. [Don’t forget to convert from joule to electronvolt when doing the calculation!] Now you can check that on the Internet too: 13.6 eV is exactly the amount of energy that’s needed to ionize a hydrogen atom (i.e. the energy that’s needed to kick the electron out of that energy well)!

Waw ! Isn’t it great that such simple calculations yield such great results? 🙂 [Of course, you’ll note that the omission of the 1/2 factor in the Uncertainty Principle was quite strategic. :-)] Using the r = 4πε0ħ2/me2 formula for the Bohr radius, you can now easily check the re = α2r formula. You should find what we jotted down already: the classical electron radius is equal to re = e2/4πε0mec2. To be precise, re = (53×10–6)·(53×10–12m) = 2.8×10–15 m. Now that’s again something you should check on the Internet. Guess what? […] It’s right on the spot again. 🙂

We can now also check that α = m·re formula: α = m·re = 4.181×10−23 times… Hey! Wait! We have to express re in Planck units as well, of course! Now, (2.81794×10–15 m)/(1.616×10–35 m) ≈ 1.7438 ×1020. So now we get 4.181×10−23 times 1.7438×1020 = 7.29×10–3 = 0.00729 ≈ 1/137. Bingo! We got the magic number once again. 🙂

So… Well… Doesn’t that confirm we actually do have it all with α?

Well… Yes and no… First, you should note that I had to use h in that calculation of the Bohr radius. Moreover, the other physical constants (most notably c and the Coulomb constant) were actually there as well, ‘in the background’ so to speak, because one needs them to derive the formulas we used above. And then we have the equations themselves, of course, most notably that Uncertainty Principle… So… Well…

It’s not like God gave us one number only (α) and that all the rest flows out of it. We have a whole bunch of ‘fundamental’ relations and ‘fundamental’ constants here.

Having said that, it’s true that statement still does not diminish the magic of alpha.

Hmm… Now you’ll wonder: how many? How many constants do we need in all of physics?

Well… I’d say, you should not only ask about the constants: you should also ask about the equations: how many equations do we need in all of physics? [Just for the record, I had to smile when the Hawking of the movie says that he’s actually looking for one formula that sums up all of physics. Frankly, that’s a nonsensical statement. Hence, I think the real Hawking never said anything like that. Or, if he did, that it was one of those statements one needs to interpret very carefully.]

But let’s look at a few constants indeed. For example, if we have c, h and α, then we can calculate the electric charge e and, hence, the electric constant ε0 = e2/2αhc. From that, we get Coulomb’s constant ke, because ke is defined as 1/4πε0… But…

Hey! Wait a minute! How do we know that ke = 1/4πε0? Well… From experiment. But… Yes? That means 1/4π is some fundamental proportionality coefficient too, isn’t it?

Wow! You’re smart. That’s a good and valid remark. In fact, we use the so-called reduced Planck constant ħ in a number of calculations, and so that involves a 2π factor too (ħ = h/2π). Hence… Well… Yes, perhaps we should consider 2π as some fundamental constant too! And, then, well… Now that I think of it, there’s a few other mathematical constants out there, like Euler’s number e, for example, which we use in complex exponentials.

?!?

I am joking, right? I am not saying that 2π and Euler’s number are fundamental ‘physical’ constants, am I? [Note that it’s a bit of a nuisance we’re also using the e symbol for Euler’s number, but so we’re not talking the electron charge here: we’re talking that 2.71828…etc number that’s used in so-called ‘natural’ exponentials and logarithms.]

Well… Yes and no. They’re mathematical constants indeed, rather than physical, but… Well… I hope you get my point. What I want to show here, is that it’s quite hard to say what’s fundamental and what isn’t. We can actually pick and choose a bit among all those constants and all those equations. As one physicist puts its: it depends on how we slice it. The one thing we know for sure is that a great many things are related, in a physical way (α connects all of the fundamental properties of the electron, for example) and/or in a mathematical way (2π connects not only the circumference of the unit circle with the radius but quite a few other constants as well!), but… Well… What to say? It’s a tough discussion and I am not smart enough to give you an unambiguous answer. From what I gather on the Internet, when looking at the whole Standard Model (including the strong force, the weak force and the Higgs field), we’ve got a few dozen physical ‘fundamental’ constants, and then a few mathematical ones as well.

That’s a lot, you’ll say. Yes. At the same time, it’s not an awful lot. Whatever number it is, it does raise a very fundamental question: why are they what they are? That brings us back to that ‘fine-tuning’ problem. Now, I can’t make this post too long (it’s way too long already), so let me just conclude this discussion by copying Wikipedia on that question, because what it has on this topic is not so bad:

“Some physicists have explored the notion that if the physical constants had sufficiently different values, our Universe would be so radically different that intelligent life would probably not have emerged, and that our Universe therefore seems to be fine-tuned for intelligent life. The anthropic principle states a logical truism: the fact of our existence as intelligent beings who can measure physical constants requires those constants to be such that beings like us can exist.“

I like this. But the article then adds the following, which I do not like so much, because I think it’s a bit too ‘frivolous’:

“There are a variety of interpretations of the constants’ values, including that of a divine creator (the apparent fine-tuning is actual and intentional), or that ours is one universe of many in a multiverse (e.g. the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics), or even that, if information is an innate property of the universe and logically inseparable from consciousness, a universe without the capacity for conscious beings cannot exist.”

Hmm… As said, I am quite happy with the logical truism: we are there because alpha (and a whole range of other stuff) is what it is, and we can measure alpha (and a whole range of other stuff) as what it is, because… Well… Because we’re here. Full stop. As for the ‘interpretations’, I’ll let you think about that for yourself. 🙂

I need to get back to the lesson. Indeed, this was just a ‘digression’. My post was about the three fundamental events or actions in quantum electrodynamics, and so I was talking about that E(A to B) formula. However, I had to do that digression on alpha to ensure you understand what I want to write about that. So let me now get back to it. End of digression. 🙂

The E(A to B) formula

Indeed, I must assume that, with all these digressions, you are truly despairing now. Don’t. We’re there! We’re finally ready for the E(A to B) formula! Let’s go for it.

We’ve now got those two numbers measuring the electron charge and the electron mass in Planck units respectively. They’re fundamental indeed and so let’s loosen up on notation and just write them as e and m respectively. Let me recap:

1. The value of e is approximately –0.08542455, and it corresponds to the so-called junction number j, which is the amplitude for an electron-photon coupling. When multiplying it with another amplitude (to find the amplitude for an event consisting of two sub-events, for example), it corresponds to a ‘shrink’ to less than one-tenth (something like 8.5% indeed, corresponding to the magnitude of e) and a ‘rotation’ (or a ‘turn’) over 180 degrees, as mentioned above.

Please note what’s going on here: we have a physical quantity, the electron charge (expressed in Planck units), and we use it in a quantum-mechanical calculation as a dimensionless (complex) number, i.e. as an amplitude. So… Well… That’s what physicists mean when they say that the charge of some particle (usually the electric charge but, in quantum chromodynamics, it will be the ‘color’ charge of a quark) is a ‘coupling constant’.

2. We also have m, the electron mass, and we’ll use in the same way, i.e. as some dimensionless amplitude. As compared to j, it’s is a very tiny number: approximately 4.181×10−23. So if you look at it as an amplitude, indeed, then it corresponds to an enormous ‘shrink’ (but no turn) of the amplitude(s) that we’ll be combining it with.

So… Well… How do we do it?

Well… At this point, Leighton goes a bit off-track. Just a little bit. 🙂 From what he writes, it’s obvious that he assumes the frequency (or, what amounts to the same, the de Broglie wavelength) of an electron is just like the frequency of a photon. Frankly, I just can’t imagine why and how Feynman let this happen. It’s wrong. Plain wrong. As I mentioned in my introduction already, an electron traveling through space is not like a photon traveling through space.

For starters, an electron is much slower (because it’s a matter-particle: hence, it’s got mass). Secondly, the de Broglie wavelength and/or frequency of an electron is not like that of a photon. For example, if we take an electron and a photon having the same energy, let’s say 1 eV (that corresponds to infrared light), then the de Broglie wavelength of the electron will be 1.23 nano-meter (i.e. 1.23 billionths of a meter). Now that’s about one thousand times smaller than the wavelength of our 1 eV photon, which is about 1240 nm. You’ll say: how is that possible? If they have the same energy, then the f = E/h and ν = E/h should give the same frequency and, hence, the same wavelength, no?

Well… No! Not at all! Because an electron, unlike the photon, has a rest mass indeed – measured as not less than 0.511 MeV/c2, to be precise (note the rather particular MeV/c2 unit: it’s from the E = mc2 formula) – one should use a different energy value! Indeed, we should include the rest mass energy, which is 0.511 MeV. So, almost all of the energy here is rest mass energy! There’s also another complication. For the photon, there is an easy relationship between the wavelength and the frequency: it has no mass and, hence, all its energy is kinetic, or movement so to say, and so we can use that ν = E/h relationship to calculate its frequency ν: it’s equal to ν = E/h = (1 eV)/(4.13567×10–15 eV·s) ≈ 0.242×1015 Hz = 242 tera-hertz (1 THz = 1012 oscillations per second). Now, knowing that light travels at the speed of light, we can check the result by calculating the wavelength using the λ = c/ν relation. Let’s do it: (2.998×108 m/s)/(242×1012 Hz) ≈ 1240 nm. So… Yes, done!

But so we’re talking photons here. For the electron, the story is much more complicated. That wavelength I mentioned was calculated using the other of the two de Broglie relations: λ = h/p. So that uses the momentum of the electron which, as you know, is the product of its mass (m) and its velocity (v): p = mv. You can amuse yourself and check if you find the same wavelength (1.23 nm): you should! From the other de Broglie relation, f = E/h, you can also calculate its frequency: for an electron moving at non-relativistic speeds, it’s about 0.123×1021 Hz, so that’s like 500,000 times the frequency of the photon we we’re looking at! When multiplying the frequency and the wavelength, we should get its speed. However, that’s where we get in trouble. Here’s the problem with matter waves: they have a so-called group velocity and a so-called phase velocity. The idea is illustrated below: the green dot travels with the wave packet – and, hence, its velocity corresponds to the group velocity – while the red dot travels with the oscillation itself, and so that’s the phase velocity. [You should also remember, of course, that the matter wave is some complex-valued wavefunction, so we have both a real as well as an imaginary part oscillating and traveling through space.]

To be precise, the phase velocity will be superluminal. Indeed, using the usual relativistic formula, we can write that p = γm0v and E = γm0c2, with v the (classical) velocity of the electron and c what it always is, i.e. the speed of light. Hence, λ = h/γm0v and f = γm0c2/h, and so λf = c2/v. Because v is (much) smaller than c, we get a superluminal velocity. However, that’s the phase velocity indeed, not the group velocity, which corresponds to v. OK… I need to end this digression.

So what? Well, to make a long story short, the ‘amplitude framework’ for electrons is differerent. Hence, the story that I’ll be telling here is different from what you’ll read in Feynman’s QED. I will use his drawings, though, and his concepts. Indeed, despite my misgivings above, the conceptual framework is sound, and so the corrections to be made are relatively minor.

So… We’re looking at E(A to B), i.e. the amplitude for an electron to go from point A to B in spacetime, and I said the conceptual framework is exactly the same as that for a photon. Hence, the electron can follow any path really. It may go in a straight line and travel at a speed that’s consistent with what we know of its momentum (p), but it may also follow other paths. So, just like the photon, we’ll have some so-called propagator function, which gives you amplitudes based on the distance in space as well as in the distance in ‘time’ between two points. Now, Ralph Leighton identifies that propagator function with the propagator function for the photon, i.e. P(A to B), but that’s wrong: it’s not the same.

The propagator function for an electron depends on its mass and its velocity, and/or on the combination of both (like it momentum p = mv and/or its kinetic energy: K.E. = mv2 = p2/2m). So we have a different propagator function here. However, I’ll use the same symbol for it: P(A to B).

So, the bottom line is that, because of the electron’s mass (which, remember, is a measure for inertia), momentum and/or kinetic energy (which, remember, are conserved in physics), the straight line is definitely the most likely path, but (big but!), just like the photon, the electron may follow some other path as well.

So how do we formalize that? Let’s first associate an amplitude P(A to B) with an electron traveling from point A to B in a straight line and in a time that’s consistent with its velocity. Now, as mentioned above, the P here stands for propagator function, not for photon, so we’re talking a different P(A to B) here than that P(A to B) function we used for the photon. Sorry for the confusion. 🙂 The left-hand diagram below then shows what we’re talking about: it’s the so-called ‘one-hop flight’, and so that’s what the P(A to B) amplitude is associated with.

Now, the electron can follow other paths. For photons, we said the amplitude depended on the spacetime interval I: when negative or positive (i.e. paths that are not associated with the photon traveling in a straight line and/or at the speed of light), the contribution of those paths to the final amplitudes (or ‘final arrow’, as it was called) was smaller.

Now, the electron can follow other paths. For photons, we said the amplitude depended on the spacetime interval I: when negative or positive (i.e. paths that are not associated with the photon traveling in a straight line and/or at the speed of light), the contribution of those paths to the final amplitudes (or ‘final arrow’, as it was called) was smaller.

For an electron, we have something similar, but it’s modeled differently. We say the electron could take a ‘two-hop flight’ (via point C or C’), or a ‘three-hop flight’ (via D and E) from point A to B. Now, it makes sense that these paths should be associated with amplitudes that are much smaller. Now that’s where that n-factor comes in. We just put some real number n in the formula for the amplitude for an electron to go from A to B via C, which we write as:

P(A to C)∗n2∗P(C to B)

Note what’s going on here. We multiply two amplitudes, P(A to C) and P(C to B), which is OK, because that’s what the rules of quantum mechanics tell us: if an ‘event’ consists of two sub-events, we need to multiply the amplitudes (not the probabilities) in order to get the amplitude that’s associated with both sub-events happening. However, we add an extra factor: n2. Note that it must be some very small number because we have lots of alternative paths and, hence, they should not be very likely! So what’s the n? And why n2 instead of just n?

Well… Frankly, I don’t know. Ralph Leighton boldly equates n to the mass of the electron. Now, because he obviously means the mass expressed in Planck units, that’s the same as saying n is the electron’s energy (again, expressed in Planck’s ‘natural’ units), so n should be that number m = meP = EeP = 4.181×10−23. However, I couldn’t find any confirmation on the Internet, or elsewhere, of the suggested n = m identity, so I’ll assume n = m indeed, but… Well… Please check for yourself. It seems the answer is to be found in a mathematical theory that helps physicists to actually calculate j and n from experiment. It’s referred to as perturbation theory, and it’s the next thing on my study list. As for now, however, I can’t help you much. I can only note that the equation makes sense.

Of course, it does: inserting a tiny little number n, close to zero, ensures that those other amplitudes don’t contribute too much to the final ‘arrow’. And it also makes a lot of sense to associate it with the electron’s mass: if mass is a measure of inertia, then it should be some factor reducing the amplitude that’s associated with the electron following such crooked path. So let’s go along with it, and see what comes out of it.

A three-hop flight is even weirder and uses that n2 factor two times:

P(A to E)∗n2∗P(E to D)∗n2∗P(D to B)